Blog

09/27/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Yra Harris & Peter Boockvar Assess Global Risks On The Economy & The Financial Markets

09/27/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Yra Harris & Peter Boockvar Assess Global Risks On The Economy & The Financial Markets

09/25/2018 - The Round Table Insight: Charles Hugh Smith Podcast (Sept 21st)

09/25/2018 - The Round Table Insight: Charles Hugh Smith Podcast (Sept 21st)

Charles Hugh Smith Podcast

By: Tenzin Lekphell

FRA: Hi! Welcome to FRA’s round table insight! This is Richard Bonugli. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith, author, leading global finance blogger, and America’s philosopher. He’s the author of nine books on our economy and society, including A Radically Beneficial World: Automation Technology and Creating Jobs for All, Resistance Revolution Liberation: A Model for Positive Change, and The Nearly Free University & The Emerging Economy. His blog oftwominds.com has logged well over 55 million page views and is number 7 on CNBC’s top alternative finance site. Welcome Charles!

Charles: Thank You Richard! I hope I live up to that very nice introduction!

FRA: Oh you always do. Thank you for being on the show! And so I think today we wanted to do a bit of a change and look at the economy as a whole and some very interesting trends that are happening, namely a software automation and robotics process automation and artificial intelligence and how that is changing the economy, the job market, how organizations are being affected by these changes, what are they doing, and if people cannot be redeployed elsewhere within our organization, what’s the answer? Do we do a lunar Apollo crash program or, you know, just some of your thoughts on that? And just like to point out so you’ve written a book on Radically beneficial world on automation technology and creating jobs so that could be quite relevant here and also a number of articles as well.

Charles: Right! Right! Well this is a fascinating topic to me Richard and so I spent a lot of time trying to get up to speed on it and of course it’s evolving so quickly that those of us that aren’t really in the field, we’re always trying to play a little bit of catch up so I’m not claiming to be cutting edge here but I think I have thought a lot about it and tried to help my readers navigate it. So, I would start with what’s the context of automation, and robotics, and AI, the impact on the economy as a whole? And I called it, this whole sector trend change, the “emerging economy” because it hasn’t yet occupied every sector of the economy but we know it will right? So that’s why I call it the emerging economy. We see it everywhere but it hasn’t yet, it’s still quite a ways from fully manifesting in every sector of the economy. And one of the issues that you raised here is what happens if we can’t employee people in a sustainable fashion at a relatively high rate of pay? Then who’s going to be supporting the consumer economy? Right? In other words, the basic answer for a lot of people is we give everyone universal basic income but that’s like a $1,000 per person per month is for the general gist of that. That’s not the equivalent of a real middle-class job. That’s just survival pay so that’s not really gonna solve that issue. So that’s one issue and that’s I think the impotence behind your question. We really need people to be working. Not only because we need their productive and capacity but we also have to give people a way to generate enough income to have a good life as prices continue to rise and so on.

FRA: Yeah exactly and what’s happening here is generally technology companies will be able to transform an organization or provide some assistance in the areas of software automation robotics, process automation, and artificial intelligence. But what happens is after some work through organizational change management, they’re able to identify other areas of the organization where those affected by the job changes can be redeployed elsewhere in the organization but it doesn’t work for everybody. Some cannot be redeployed elsewhere within the organization and so they would be let go and then it becomes a societal problem or a government problem at that point. So that’s the big question what happens at that point?

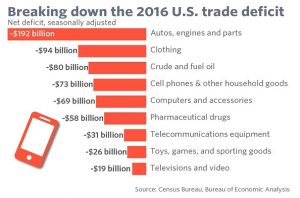

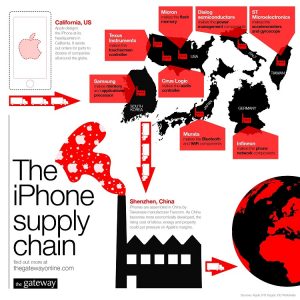

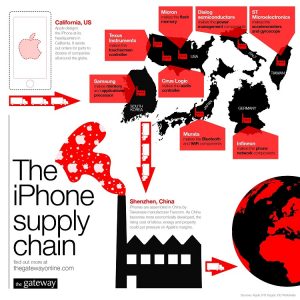

Charles: Right! Just to provide some context, I have assembled a few graphics here that will help us, I hope, contextualize your question. The first is the iPhone supply chain, which goes to show just how global the tech economy is.

Now of course, this is not the entire economy because I read somebody noted recently on the internet that you can’t get a haircut on the internet. Right? So my point here is with the iPhone supply chain is to show that automation is a global phenomenon right? Their automating in China despite the lower labour cost because the labour costs is rising there too. So it’s not just an advanced economy problem, it’s global.

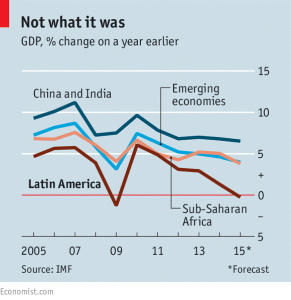

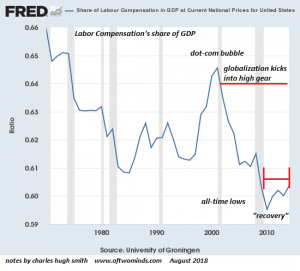

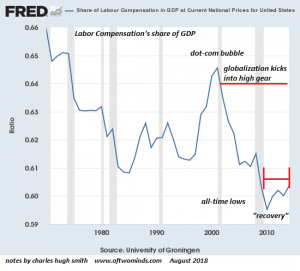

And my next chart here is the labour share of the GDP.

In other words, how much of the gross domestic product (inaudible 6:01-6:02) how much does that end up in the hands of labour as opposed to capital or other investment? We can see from this chart that labour share rose considerably in the dot com era because there was a huge expansion of employment to build out the basic infrastructure of the internet and so that created a lot of real employment. But when that got built out then the labour share of the GDP plummeted and it hasn’t recovered despite the so-called global recovery. So my point here is to show that we really need to keep labour share of the GDP high enough to support consumption or else the model of our economy no longer works.

In other words, how much of the gross domestic product (inaudible 6:01-6:02) how much does that end up in the hands of labour as opposed to capital or other investment? We can see from this chart that labour share rose considerably in the dot com era because there was a huge expansion of employment to build out the basic infrastructure of the internet and so that created a lot of real employment. But when that got built out then the labour share of the GDP plummeted and it hasn’t recovered despite the so-called global recovery. So my point here is to show that we really need to keep labour share of the GDP high enough to support consumption or else the model of our economy no longer works.

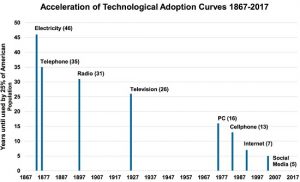

My next chart is the acceleration of technological adoption.

Of course we all feel this intuitively but this points out that it took like 26 years for television to become ubiquitous and then it took social media only 5 years. So this puts a lot pressure on individuals and organizations because we can see this trend of automation is speeding up. It’s accelerating. It’s almost like whatever skill you learned in college, if it’s 4 years later, you’re already behind the curve. It requires, more or less, constant learning because of this accelerating adoption rate.

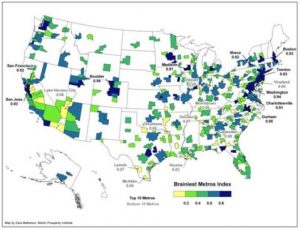

Although we’re talking about the economy as a whole, I have a graphic here of the United States which is an example of an advanced economy, you could call up a map of China or Japan or Europe and have a similar discussion.

The so called creative class, sort of the generalized term for people with higher education degrees and experience in the emerging economy, these of course are clustered in certain areas. So we’re really talking about two separate economies. So when we try to answer your important question, what do we do with people who aren’t able to transition to an emerging technology kind of economy? It’s a regional thing too because obviously the places like the San Francisco Bay area and equivalent places have the human capital, If you will, to address these issues better then areas with a less educated, with less mobile kind of employment foundation.

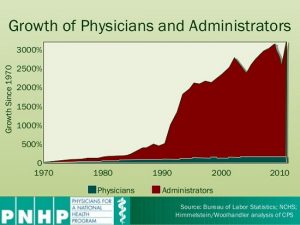

My next chart shows, this is in the health care sector in the United States which we all know is troubled for a lot of reasons, that the number of physicians have been added to the sector is minimal in the last 30 to 40 years where the growth of administrators is up about 3000%.

So I bring this chart to our attention as an example of a sector that is obviously ripe for disruption and there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit in terms of work that could be automated or streamlined in sectors like health care. In other words, this is not just high tech like we’re not talking about chip design or social media or mobile apps, we’re looking at these very large sectors that employ millions of people which are ripe for disruption by the forces that we’re talking about here.

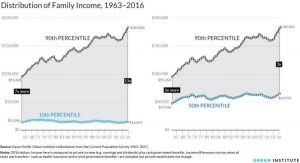

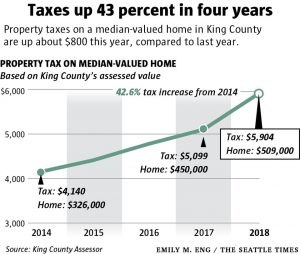

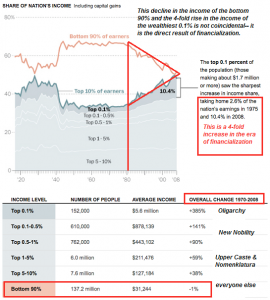

My last chart is distribution of family income which shows, that as we all know, the top 10% has basically lifted away from the bottom 90% in terms of income.

The reason why I bring this up is, there is a lot of reasons for that, but one of them is that this top 10% tends to be the most highly educated, the most dynamic sector of the population. They’re the ones that are acquiring the skills and managerial skills to navigate the emerging economy and this is reflected in their much higher income. And this is the danger of a what we’re talking about here is even if we can maintain some generalized employment, if most of the rewards are going into the top ten percent then that also called into question or our whole mass consumption model of our economy. Now having said all that, how are organisations being affected by this change and how is it affecting the job market and how do how do organizations take the initiative to redeploy or train resources affected by these? These are all excellent questions and of course it depends on the sector. Say, just to give a brief example, the construction industry. There’s a certain amount of technological innovation there in terms of components fabricated in a factory and then shipped and assembled on site to reduce labour but there’s a lot of, let’s say, remodelling work. It’s very hard to automate that kind of stuff because it’s unique to each particular dwelling or each project and we still need workers with multiple skill sets.

So I think as a general rule, what we want to train our people for, whether there within our organization or if their students or laid-off workers is we want to give people a menu of skill sets not just a specialty. I mean a specialty skills works great if you are designing really high-end chip sets or you’re a physician but like for the rest of the populist, specialization means that you can be replaced by automation a lot easier than if you can have multiple skills. That’s one issue here is that we want to broaden peoples skill set. Another thought here is that some labours are hard to automate like creative work, design, editing, etc. But even those kinds of advanced skill sets are being are being automated too as automation eats its way up the food chain.

Another sector of work that’s fairly protected is managing people, you know managerial skills which is really hard to automate and also any kind of employment that’s based on high touch. What’s known as high touch, meaning that your interacting with humans is what creates the value of your employment and so of course it’s going to be like nursing and childcare and so.

I think what we’re really talking about here when talk about how to organization responds, we’re talking not about those professions that are very difficult to automate but we’re talking about the professions that have to work with automation. They may not be completely replaced but it demands the employee’s augment the processes and learn enough to increase productivity because that’s another thing we’re talking about here as automation and A.I spread throughout the economy, we’re finding productivity is still stagnating. So we’re not really getting the gains of that. I mean you must have some thoughts about that too right? Because technology is supposed to enhance productivity. That’s the wealth creation part.

FRA: Yeah, and you’ve also explored in recent writing as well how organizations are being affected by these changes. Not only as you just mentioned on the productivity results but also on profits. Can you elaborate on that? And in recent writings, you mention that the automation doesn’t just destroy jobs, it destroys profits too.

Charles: Right and that’s counterintuitive for a lot of people Richard because they assume that the robot, because it’s replacing human labor and it’s cheaper, that it’s kind of generate huge profits or the other company that replaced their employees with robots but it doesn’t work like that and the reason why is “commoditization”. When we commoditize something, whether it’s labour or capital or goods, it means that they’re interchangeable. They can be produced anywhere in the world and so this is what the globalization phenomenon has (inaudible 15:41) why it’s reduced cost so much is labour is interchangeable, computer chips are interchangeable, computer design centres are interchangeable so a robot is like a good example of a commoditized tool where anybody can buy the same robot that I bought and they can put it on their line. So therefore where’s my scarcity value? Where’s my Competitive Edge? and so as soon as you get robots involved then profits fall because everything becomes a commodity and we can see this in technology that when something is commoditized, the value drops, the price drops, and the profit margins drop to near 0. Like for instance a tablet. Right now if you have the special software that Apple sells right it’s tightly bound to its Hardware, that’s their scarcity value you can only get the certain features that Apple has by spending $400 on an iPad right? But if you’re going to get a generic tablet, those are like 30 bucks a piece in China with free software loaded and they have to have an 80 or 90% of the capability of the more expensive one. That’s the same thing that’s gonna happen to robotics. Everybody can buy the same Robotics and a lot of the tools why automation are free or software they’re free or they’re very cheap. So that’s why profits are going to plummet as automation enters the supply chain.

FRA: Interesting! And in terms of how organizations are addressing this, I think it’s also interesting to note how you can almost divide the pool of resources into some certain scenarios. One is the resources that need to be trained for extra skill sets on how to manage the increased level of automation or robotic process automation or artificial intelligence that will come into play in the organization. And then there’s others that would need to be redeployed within the organization elsewhere overall increasing productivity in that way. And then there’s the pool that where there’s no opportunities identified. They are not able to do increased levels of activity of services and they’re not in the pool of being able to be redeployed elsewhere. Your thoughts on that?

Charles: Right! It’s an excellent point Richard and this was really why I wrote my book A Radically Beneficial World is what I was proposing was that there is a very large pool of workers who don’t have the value system, the ambition, this sort of background perhaps to take on the extreme challenge of learning a bunch of high technology skills sets. And of those people, many of them have other kinds of intelligence. In other words, we need to help people identify where their strengths are. So for instance, some people have great manual intelligence. They can work with very fine machinery, some of which is of course related to robotics.

FRA: Now what can we do about this? Should governments take a role in redeploying or training resources affected by these changes? So that this would be the pool of resources that are unable to be redeployed within the organization or that’s still continued to have an expanded role in their current positions and job functions. So what can government do in this regard? Does it make sense to have government play a role your thoughts?

Charles: That’s a great question Richard and I think we can discern two approaches here. One is direct government spending, like on infrastructure a lot of people think of that, but it’s also the government could streamline a lot of really clunky processes we have now and in it (inaudible 20:21-20:22) both have, you know, a lower-level high school education and also higher education. So there’s opportunities for the government to contribute to the solutions in two ways; simplifying and enhancing processes that’s already involved in and then direct spending.

FRA: What about Reliance on the Invisible Hand of Adam Smith? So you know would that play a role here in terms of inner resources able to self-identify or self-train into other areas of the economy?

Charles: Right, it’s a great question and it’s always an issue I think in a state market economy which describes most of the global economy now right that the government’s around the world are heavily engaged or involved in managing their private sector. And so a lot of people have a sort of Quasi-religious belief that the market can solve everything but there certainly seems to be examples in which government does need to play a role in terms of providing infrastructure for everybody so that everybody has equal opportunity within a society. It’s something that isn’t necessarily profitable for enterprise to supply those things. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t right? The canals in the early of the 18th century in America were privately-funded. But to use the example you mentioned earlier the Apollo Mission to the moon, obviously there was no a market demand for that and so no one was going to put up money or capital because there was no profit to be earned and because there was no market. In my book A Radically Beneficial World, I talk about the community economy as a place where we, the government, could redeploy capital because there’s lot of work to be done in local communities (inaudible 22:47 to 22:48) do the work because it’s just not profitable enough for them. But governments are often heavy handed and there are a lot of programs like job training end up failing. They don’t produce desired results. That’s not a clear answer but I think there’s multiple levels of opportunity for government. Sometimes just providing some infrastructure, sometimes smoothing the path so that work private capital can get to work without a lot of red tape and regulation.

FRA: And what about the lunar Apollo crash program back in the 1960s? There’s estimates that perhaps somewhere between $4 and $8 in economic growth, economic activity was generated for every $1 invested into that program. So maybe could that be considered in terms of doing another crash type of program but in something else that makes sense today like you know nuclear fusion energy development coupled with the electrification of cars for example. Would that make sense it in create jobs not only in the white collar jobs but also blue collar jobs across the entire nation?

Charles: That’s a great question Richard. I think a lot of people are looking to that idea as a major solution. A big government spending program on something that was particularly useful, which would be energy, because we all know we need to transition away from fossil fuels. There’s a cautionary part of that idea and I looked to Japan as an example of the cautionary part. Japan has spent almost 30 years spending a tremendous amount of fiscal stimulus on infrastructure and what they done is mal-invested much of it in bridges to nowhere and high-ways very few people used and this is a result of their political system which gives a lot of power to the construction industry. Sadly, they in my view, they squandered trillions of Yen on infrastructure that really didn’t serve the entire citizenry as well as if they solarize their economy or done something that was more to the common good instead of just kind of make work projects. So we have to be careful here that we’re not just funding make work jobs, we want to leverage some technology that benefits the greater good. One example, and a lot of people talk about this, is upgrading the electrical grid because this is something that is required in order make use of electrical production from solar and wind. It’s increasing right? That grid has to be completely upgraded. So that’s an example of a program that sort of fits those parameters so that it would leverage government investment to the benefit of the private sector as well as to the citizenry. Of course everybody loves the example of the Arpanet, which was the original little government funded program that spawned the entire internet right? That was a really low cost investment and so I think we can talk about that too like it’s easy to talk about spending a trillion dollars, and everybody wants to spend a trillion, but maybe we should start by just trying to see what we could do with smaller sums to leverage new technologies and make them available to a wider range of people like 3D fabrication technology. That could be beneficial if the government invested in spreading that around and that should be a lot less expensive than big trillion-dollar programs.

FRA: Interesting. And finally how do you see all of this playing out in the long-term? Do you see like a combination of government taking a role, the invisible hand of Adam Smith or potential crash programs in the future?

Charles: Right! It’s a very dynamic situation and I would hesitate to make any predictions but I think the potential for disruption is so large that the government itself should be disrupted. In other words, we need to disrupt, to which we apply the technologies that we were discussing. We need to apply them to lower the cost and increase the effectiveness of government itself. And so when we talk about government spending, one of the first places we should invest in is streamlining government because it’s really, and it in so many ways, inefficient and ineffective and it desperately needs to be disrupted in streamlined. So that that might be a first place to start investing taxpayer money.

FRA: Wow, great insight as always Charles. How can our listeners learn more about your work?

Charles: Yeah, please visit me oftwominds.com, and you can read samples of my most recent books.

FRA: Great! Thank you very much for being on the program show for your insights on this very interesting topic.

Charles: Oh yeah, we barely touched the surface. Thank you so much for inviting me on the program!

09/24/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On Insights Into The Jobs For Displaced Workers Affected By Intelligent Automation

09/24/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On Insights Into The Jobs For Displaced Workers Affected By Intelligent Automation

Charles Hugh Smith Podcast

By: Tenzin Lekphell

FRA: Hi! Welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight! .. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith, author, leading global finance blogger, and America’s philosopher. He’s the author of nine books on our economy and society, including A Radically Beneficial World: Automation Technology and Creating Jobs for All, Resistance Revolution Liberation: A Model for Positive Change, and The Nearly Free University & The Emerging Economy. His blog oftwominds.com has logged well over 55 million page views and is number 7 on CNBC’s top alternative finance site. Welcome Charles!

Charles: Thank You Richard! I hope I live up to that very nice introduction!

FRA: Oh you always do. Thank you for being on the show! And so I think today we wanted to do a bit of a change and look at the economy as a whole and some very interesting trends that are happening, namely a software automation and robotics process automation and artificial intelligence and how that is changing the economy, the job market, how organizations are being affected by these changes, what are they doing, and if people cannot be redeployed elsewhere within our organization, what’s the answer? Do we do a lunar Apollo crash program or, you know, just some of your thoughts on that? And just like to point out so you’ve written a book on Radically beneficial world on automation technology and creating jobs so that could be quite relevant here and also a number of articles as well.

Charles: Right! Right! Well this is a fascinating topic to me Richard and so I spent a lot of time trying to get up to speed on it and of course it’s evolving so quickly that those of us that aren’t really in the field, we’re always trying to play a little bit of catch up so I’m not claiming to be cutting edge here but I think I have thought a lot about it and tried to help my readers navigate it. So, I would start with what’s the context of automation, and robotics, and AI, the impact on the economy as a whole? And I called it, this whole sector trend change, the “emerging economy” because it hasn’t yet occupied every sector of the economy but we know it will right? So that’s why I call it the emerging economy. We see it everywhere but it hasn’t yet, it’s still quite a ways from fully manifesting in every sector of the economy. And one of the issues that you raised here is what happens if we can’t employee people in a sustainable fashion at a relatively high rate of pay? Then who’s going to be supporting the consumer economy? Right? In other words, the basic answer for a lot of people is we give everyone universal basic income but that’s like a $1,000 per person per month is for the general gist of that. That’s not the equivalent of a real middle-class job. That’s just survival pay so that’s not really gonna solve that issue. So that’s one issue and that’s I think the impotence behind your question. We really need people to be working. Not only because we need their productive and capacity but we also have to give people a way to generate enough income to have a good life as prices continue to rise and so on.

FRA: Yeah exactly and what’s happening here is generally technology companies will be able to transform an organization or provide some assistance in the areas of software automation robotics, process automation, and artificial intelligence. But what happens is after some work through organizational change management, they’re able to identify other areas of the organization where those affected by the job changes can be redeployed elsewhere in the organization but it doesn’t work for everybody. Some cannot be redeployed elsewhere within the organization and so they would be let go and then it becomes a societal problem or a government problem at that point. So that’s the big question what happens at that point?

Charles: Right! Just to provide some context, I have assembled a few graphics here that will help us, I hope, contextualize your question. The first is the iPhone supply chain, which goes to show just how global the tech economy is.

Now of course, this is not the entire economy because I read somebody noted recently on the internet that you can’t get a haircut on the internet. Right? So my point here is with the iPhone supply chain is to show that automation is a global phenomenon right? Their automating in China despite the lower labour cost because the labour costs is rising there too. So it’s not just an advanced economy problem, it’s global.

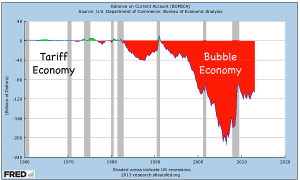

And my next chart here is the labour share of the GDP.

In other words, how much of the gross domestic product (inaudible 6:01-6:02) how much does that end up in the hands of labour as opposed to capital or other investment? We can see from this chart that labour share rose considerably in the dot com era because there was a huge expansion of employment to build out the basic infrastructure of the internet and so that created a lot of real employment. But when that got built out then the labour share of the GDP plummeted and it hasn’t recovered despite the so-called global recovery. So my point here is to show that we really need to keep labour share of the GDP high enough to support consumption or else the model of our economy no longer works.

In other words, how much of the gross domestic product (inaudible 6:01-6:02) how much does that end up in the hands of labour as opposed to capital or other investment? We can see from this chart that labour share rose considerably in the dot com era because there was a huge expansion of employment to build out the basic infrastructure of the internet and so that created a lot of real employment. But when that got built out then the labour share of the GDP plummeted and it hasn’t recovered despite the so-called global recovery. So my point here is to show that we really need to keep labour share of the GDP high enough to support consumption or else the model of our economy no longer works.

My next chart is the acceleration of technological adoption.

Of course we all feel this intuitively but this points out that it took like 26 years for television to become ubiquitous and then it took social media only 5 years. So this puts a lot pressure on individuals and organizations because we can see this trend of automation is speeding up. It’s accelerating. It’s almost like whatever skill you learned in college, if it’s 4 years later, you’re already behind the curve. It requires, more or less, constant learning because of this accelerating adoption rate.

Although we’re talking about the economy as a whole, I have a graphic here of the United States which is an example of an advanced economy, you could call up a map of China or Japan or Europe and have a similar discussion.

The so called creative class, sort of the generalized term for people with higher education degrees and experience in the emerging economy, these of course are clustered in certain areas. So we’re really talking about two separate economies. So when we try to answer your important question, what do we do with people who aren’t able to transition to an emerging technology kind of economy? It’s a regional thing too because obviously the places like the San Francisco Bay area and equivalent places have the human capital, If you will, to address these issues better then areas with a less educated, with less mobile kind of employment foundation.

My next chart shows, this is in the health care sector in the United States which we all know is troubled for a lot of reasons, that the number of physicians have been added to the sector is minimal in the last 30 to 40 years where the growth of administrators is up about 3000%.

So I bring this chart to our attention as an example of a sector that is obviously ripe for disruption and there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit in terms of work that could be automated or streamlined in sectors like health care. In other words, this is not just high tech like we’re not talking about chip design or social media or mobile apps, we’re looking at these very large sectors that employ millions of people which are ripe for disruption by the forces that we’re talking about here.

My last chart is distribution of family income which shows, that as we all know, the top 10% has basically lifted away from the bottom 90% in terms of income.

The reason why I bring this up is, there is a lot of reasons for that, but one of them is that this top 10% tends to be the most highly educated, the most dynamic sector of the population. They’re the ones that are acquiring the skills and managerial skills to navigate the emerging economy and this is reflected in their much higher income. And this is the danger of a what we’re talking about here is even if we can maintain some generalized employment, if most of the rewards are going into the top ten percent then that also called into question or our whole mass consumption model of our economy. Now having said all that, how are organisations being affected by this change and how is it affecting the job market and how do how do organizations take the initiative to redeploy or train resources affected by these? These are all excellent questions and of course it depends on the sector. Say, just to give a brief example, the construction industry. There’s a certain amount of technological innovation there in terms of components fabricated in a factory and then shipped and assembled on site to reduce labour but there’s a lot of, let’s say, remodelling work. It’s very hard to automate that kind of stuff because it’s unique to each particular dwelling or each project and we still need workers with multiple skill sets.

So I think as a general rule, what we want to train our people for, whether there within our organization or if their students or laid-off workers is we want to give people a menu of skill sets not just a specialty. I mean a specialty skills works great if you are designing really high-end chip sets or you’re a physician but like for the rest of the populist, specialization means that you can be replaced by automation a lot easier than if you can have multiple skills. That’s one issue here is that we want to broaden peoples skill set. Another thought here is that some labours are hard to automate like creative work, design, editing, etc. But even those kinds of advanced skill sets are being are being automated too as automation eats its way up the food chain.

Another sector of work that’s fairly protected is managing people, you know managerial skills which is really hard to automate and also any kind of employment that’s based on high touch. What’s known as high touch, meaning that your interacting with humans is what creates the value of your employment and so of course it’s going to be like nursing and childcare and so.

I think what we’re really talking about here when talk about how to organization responds, we’re talking not about those professions that are very difficult to automate but we’re talking about the professions that have to work with automation. They may not be completely replaced but it demands the employee’s augment the processes and learn enough to increase productivity because that’s another thing we’re talking about here as automation and A.I spread throughout the economy, we’re finding productivity is still stagnating. So we’re not really getting the gains of that. I mean you must have some thoughts about that too right? Because technology is supposed to enhance productivity. That’s the wealth creation part.

FRA: Yeah, and you’ve also explored in recent writing as well how organizations are being affected by these changes. Not only as you just mentioned on the productivity results but also on profits. Can you elaborate on that? And in recent writings, you mention that the automation doesn’t just destroy jobs, it destroys profits too.

Charles: Right and that’s counterintuitive for a lot of people Richard because they assume that the robot, because it’s replacing human labor and it’s cheaper, that it’s kind of generate huge profits or the other company that replaced their employees with robots but it doesn’t work like that and the reason why is “commoditization”. When we commoditize something, whether it’s labour or capital or goods, it means that they’re interchangeable. They can be produced anywhere in the world and so this is what the globalization phenomenon has (inaudible 15:41) why it’s reduced cost so much is labour is interchangeable, computer chips are interchangeable, computer design centres are interchangeable so a robot is like a good example of a commoditized tool where anybody can buy the same robot that I bought and they can put it on their line. So therefore where’s my scarcity value? Where’s my Competitive Edge? and so as soon as you get robots involved then profits fall because everything becomes a commodity and we can see this in technology that when something is commoditized, the value drops, the price drops, and the profit margins drop to near 0. Like for instance a tablet. Right now if you have the special software that Apple sells right it’s tightly bound to its Hardware, that’s their scarcity value you can only get the certain features that Apple has by spending $400 on an iPad right? But if you’re going to get a generic tablet, those are like 30 bucks a piece in China with free software loaded and they have to have an 80 or 90% of the capability of the more expensive one. That’s the same thing that’s gonna happen to robotics. Everybody can buy the same Robotics and a lot of the tools why automation are free or software they’re free or they’re very cheap. So that’s why profits are going to plummet as automation enters the supply chain.

FRA: Interesting! And in terms of how organizations are addressing this, I think it’s also interesting to note how you can almost divide the pool of resources into some certain scenarios. One is the resources that need to be trained for extra skill sets on how to manage the increased level of automation or robotic process automation or artificial intelligence that will come into play in the organization. And then there’s others that would need to be redeployed within the organization elsewhere overall increasing productivity in that way. And then there’s the pool that where there’s no opportunities identified. They are not able to do increased levels of activity of services and they’re not in the pool of being able to be redeployed elsewhere. Your thoughts on that?

Charles: Right! It’s an excellent point Richard and this was really why I wrote my book A Radically Beneficial World is what I was proposing was that there is a very large pool of workers who don’t have the value system, the ambition, this sort of background perhaps to take on the extreme challenge of learning a bunch of high technology skills sets. And of those people, many of them have other kinds of intelligence. In other words, we need to help people identify where their strengths are. So for instance, some people have great manual intelligence. They can work with very fine machinery, some of which is of course related to robotics.

FRA: Now what can we do about this? Should governments take a role in redeploying or training resources affected by these changes? So that this would be the pool of resources that are unable to be redeployed within the organization or that’s still continued to have an expanded role in their current positions and job functions. So what can government do in this regard? Does it make sense to have government play a role your thoughts?

Charles: That’s a great question Richard and I think we can discern two approaches here. One is direct government spending, like on infrastructure a lot of people think of that, but it’s also the government could streamline a lot of really clunky processes we have now and in it (inaudible 20:21-20:22) both have, you know, a lower-level high school education and also higher education. So there’s opportunities for the government to contribute to the solutions in two ways; simplifying and enhancing processes that’s already involved in and then direct spending.

FRA: What about Reliance on the Invisible Hand of Adam Smith? So you know would that play a role here in terms of inner resources able to self-identify or self-train into other areas of the economy?

Charles: Right, it’s a great question and it’s always an issue I think in a state market economy which describes most of the global economy now right that the government’s around the world are heavily engaged or involved in managing their private sector. And so a lot of people have a sort of Quasi-religious belief that the market can solve everything but there certainly seems to be examples in which government does need to play a role in terms of providing infrastructure for everybody so that everybody has equal opportunity within a society. It’s something that isn’t necessarily profitable for enterprise to supply those things. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t right? The canals in the early of the 18th century in America were privately-funded. But to use the example you mentioned earlier the Apollo Mission to the moon, obviously there was no a market demand for that and so no one was going to put up money or capital because there was no profit to be earned and because there was no market. In my book A Radically Beneficial World, I talk about the community economy as a place where we, the government, could redeploy capital because there’s lot of work to be done in local communities (inaudible 22:47 to 22:48) do the work because it’s just not profitable enough for them. But governments are often heavy handed and there are a lot of programs like job training end up failing. They don’t produce desired results. That’s not a clear answer but I think there’s multiple levels of opportunity for government. Sometimes just providing some infrastructure, sometimes smoothing the path so that work private capital can get to work without a lot of red tape and regulation.

FRA: And what about the lunar Apollo crash program back in the 1960s? There’s estimates that perhaps somewhere between $4 and $8 in economic growth, economic activity was generated for every $1 invested into that program. So maybe could that be considered in terms of doing another crash type of program but in something else that makes sense today like you know nuclear fusion energy development coupled with the electrification of cars for example. Would that make sense it in create jobs not only in the white collar jobs but also blue collar jobs across the entire nation?

Charles: That’s a great question Richard. I think a lot of people are looking to that idea as a major solution. A big government spending program on something that was particularly useful, which would be energy, because we all know we need to transition away from fossil fuels. There’s a cautionary part of that idea and I looked to Japan as an example of the cautionary part. Japan has spent almost 30 years spending a tremendous amount of fiscal stimulus on infrastructure and what they done is mal-invested much of it in bridges to nowhere and high-ways very few people used and this is a result of their political system which gives a lot of power to the construction industry. Sadly, they in my view, they squandered trillions of Yen on infrastructure that really didn’t serve the entire citizenry as well as if they solarize their economy or done something that was more to the common good instead of just kind of make work projects. So we have to be careful here that we’re not just funding make work jobs, we want to leverage some technology that benefits the greater good. One example, and a lot of people talk about this, is upgrading the electrical grid because this is something that is required in order make use of electrical production from solar and wind. It’s increasing right? That grid has to be completely upgraded. So that’s an example of a program that sort of fits those parameters so that it would leverage government investment to the benefit of the private sector as well as to the citizenry. Of course everybody loves the example of the Arpanet, which was the original little government funded program that spawned the entire internet right? That was a really low cost investment and so I think we can talk about that too like it’s easy to talk about spending a trillion dollars, and everybody wants to spend a trillion, but maybe we should start by just trying to see what we could do with smaller sums to leverage new technologies and make them available to a wider range of people like 3D fabrication technology. That could be beneficial if the government invested in spreading that around and that should be a lot less expensive than big trillion-dollar programs.

FRA: Interesting. And finally how do you see all of this playing out in the long-term? Do you see like a combination of government taking a role, the invisible hand of Adam Smith or potential crash programs in the future?

Charles: Right! It’s a very dynamic situation and I would hesitate to make any predictions but I think the potential for disruption is so large that the government itself should be disrupted. In other words, we need to disrupt, to which we apply the technologies that we were discussing. We need to apply them to lower the cost and increase the effectiveness of government itself. And so when we talk about government spending, one of the first places we should invest in is streamlining government because it’s really, and it in so many ways, inefficient and ineffective and it desperately needs to be disrupted in streamlined. So that that might be a first place to start investing taxpayer money.

FRA: Wow, great insight as always Charles. How can our listeners learn more about your work?

Charles: Yeah, please visit me oftwominds.com, and you can read samples of my most recent books.

FRA: Great! Thank you very much for being on the program show for your insights on this very interesting topic.

Charles: Oh yeah, we barely touched the surface. Thank you so much for inviting me on the program!

08/23/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: Yra Harris & Peter Boockvar On Global Risks And Central Bank Policy Trends

08/23/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: Yra Harris & Peter Boockvar On Global Risks And Central Bank Policy Trends

Yra & Peter Podcast

By: Tenzin Lekphell

FRA: Hi welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight .. Today we have Yra Harris and Peter Boockvar. Yra is a successful hedge fund manager and a global trader in foreign currencies, bonds, commodities, and equities for over 40 years. He was also a CME director from 1997 to 2003. And Peter is Chief Investment Officer for the Bleakley Financial Group and Advisory. He has a newsletter product called the BoockReport.com which has great macro-economic insight and respective with lots of updates of economic indicators. Welcome Gentlemen!

Yra: Hey Richard!

Peter: Hey good afternoon guys!

FRA: Great! I thought we begin with a reflection on the FOMC Minutes today and the observation that you made recently Yra and your blog that Peter Boockvar, Jim Bianco, and the former Bank of India governor, Raghuram Rajan, have all raised concerns about the Feds raising rates while shrinking its balance sheet. This is leading to a rapid rise in borrowing costs for emerging market economies that have high levels of dollars denominated debt. And so what is the consensus today from the FOMC minutes meeting perspective?

Yra: Well I am sure Peter will speak more to the FOMC Minutes. I have read through some and I am sure he’s much more ahead of me on this but you know Peter and Jim and certainly professor Rajan have discussed this and its impact on the ripple effect. You know every central bank because the media is so enamored and the fact the equity market has risen and the central banks all raised the great concept of counter factual wealth we haven’t done this. Well they did do this and I know that Peter and I and Richard you have discussed this for years they have overstayed this hand and did they need Q.E 2 or 3. But the effects of the Bernanke Fed taking this, to me a ridiculous and which prompted the Yishibe and of course The Bank of Japan to take this to ridiculous end, have sent global interest rate to very low levels and I think has enabled, I think that’s the right word, cause when we enable an addiction to this ultra-low interest rate and led this to a huge amount of borrowing because of these low rates. Now that interest rates are moving up as Peter pointed out since he framed the QT or Quantitative tightening, that now liquidity is being withdrawn especially from the world reserve currency, which has greater effects than any other. And it causing some dislocation because interest rates are going up and we feel liquidity is tightening and now this you know, all these people who are borrowed up are now having to paying it back or if they are not paying it back yet, their debt services costs will rise dramatically. So that’s where we sit in the world so I think it has great ramifications but I will leave my voice there and let Peter go on with it.

Peter: Yeah, I agree with Yra’s points and one ironic thing about Monetary Policy is that when you look at that over 20 years ago, each successive cycle saw lower and lower interest rates because the debt build up that has taken over many years meant that we needed lower and lower interest rates not only which encourage the borrowing but meant that higher rates than that would cause a major problems cause of all the debt so here the Feds says I’m going to cover it to zero and I’m going to encourage you guys to go out and borrow and borrow and borrow and now you have taken on a lot of debt now its time to raise interest rates well they can’t raise the interest rates to much because of all the debt that’s accumulated. So we are going to the next recession or down turn whenever that might occur with the fed funds rate well below what it’s been in the past. Likely Europe will go into to the next recession with rates that are negative and Japan will probably do the same. So that’s what going to differentiate the next recession from the previous ones is the inability of central banks to be able deal with it because so many (4:52 Inaudible) have already been expended. So one of the problems there to leave it at that. But with respect to Yra mentioned the Minutes, The Minutes are in a way in addition to FOMC statement, the minutes are not really minutes. When you think of minutes, it’s okay let’s take notes of about what discussed. The fed has turned Minutes into another messaging machine, to be sort of an addendum to the Minutes the actual statements that comes out the day of the meeting. And typically nothing comes of it and I don’t really think nothing really came of it this time but those that think that the Feds are going to be talking about trading and worried about that that there are going to be almost done, well there are plenty of comments within the minutes that talked about company’s having more leverage in raising prices. There is also a great discussion on the yield curve with some saying that we outta to pay attention to the yield curve and we don’t want to invert it. And others have said that you can’t infer economic casualty from some statistics correlation because there global factors that are surpassing long term interest rates such as, as Yra said, very low rates in Europe and Japan. The question is to which side is of that argument is Jay Powell and I’m not sure of that answer.

FRA: Okay and what about the effect of this on the US equities markets Yra you observed that there’s a rallying of the US markets relative to the rest of the world with the (6:32 inaudible) US dollar. Could this be a trend, a change in trend from prior correlation of weak currency and strong equities market?

Yra: Well you know with the algorithmic world and the way we respond to things, can it be a trend? I do not how to define trend anymore. You know it seems 24 hours is a momentum trend so it switches again. So in the big picture, I don’t believe that those fundamental have shifted dramatically and I always find the currency are (7:06 inaudible) interesting because they will roll out, you know I love the different financial media because they will roll out a CEO who when the dollar is rallying or its affecting our outlier that is affecting our profitability of the strong dollar but I yet to hear of a CEO in America who when the dollar is weak and the profits are growing stand up and say, “don’t increase my bonus this year cause its really due to extraordinary circumstances way beyond my control and that’s the dollar is so weak that you couldn’t help but make money”. So the argument about the dollar it’s right now you got both going together because of some theory that the United States is some haven for money flowing in, it’s still the same thing in China with a weak currency but you have a real weak equity market. These are things that we haven’t seen sustain themselves and I don’t believe they will sustain themselves as far as equity markets correlative with currencies that they will have long held view will resurrect itself, But right now we are in a situation where several correlation that we have seen have broken down we also saw oil prices rally with quite a bit with the dollar rally initially. So you know what that’s the thing about correlation they work until they don’t work anymore. But certain along the held relationships we will always reassert themselves. I almost sound like the feds giving enough time (8:56 – 9:01 inaudible)

FRA: And your thoughts Peter?

Peter: Yeah I agree. Even with the European stock markets this year with the recent weakness in the Euro it has done nothing to help the European markets. (Inaudible 9:15) in Germany in which, 40% depended on exports. So and to the point of algorithms, I stopped thinking that equity market was a good discounting mechanism like it used to be and I see it just for responding to events and circumstances that’s smack in the middle of its face and like you take now for example, you see the weakness in overseas economies. Well 40% of the S&P sources goods from overseas but there is not one (Inaudible 9:48) saying that our revenue growth can be clipped here. To think a lot of it does have to do with Algorithms cause in algorithm the input is the data that is out here. It’s not guessing what the data will be. So it’s not saying that China’s growth is falling therefore 6 months from now, it will start to impact the US and I should trim equities today. Its saying, China’s growth is slowing but it hasn’t affected the US and the US is still good therefore buy stocks. So I wouldn’t look at US equity market as a good discounting mechanism just look at 07. The credit markets were literally on fire in the beginning of 07 and the stock market hit an all-time record high in October 2007 because the feds were cutting rates and they thought the feds are here to save us. Buy stocks when they cut rates. In the flipside, buy stocks 2013, 14, 15, don’t fight the feds don’t fight the feds. Well now, you don’t hear anyone talking about, “be careful of feds be careful of feds”. It’s just buy stocks buy stocks things are good! So the narrative always changes and the circle of relationships are difficult to apply now because we never had an experience of negative interest rates. The (inaudible 11:05) 2 years minus 60 basis point historical approximate so don’t give me a seasonal analysis or historical analysis of the yield curve when we are in a rate environment when it’s never been seen in the history of the world before.

Yra: (11:22 inaudible) because you’re in Canada Richard so one of the most interesting things is the flattest yield curve, except outside Iceland which is a different situation, but the Canadian curve is really flat. Flatter than the US. I think its 15 basis points this morning. Which is interesting because they never had a Q.E program. So what is flattening the curve? Is it that the Canadian are now following the US in raising the rates and that the Canadian market a very effective barometer that hey, “you might be wrong here that there are things you ought not to be raising rates in this fashion. I find that very interesting what the Canadian curve is doing and I’m starting to pay attention to it only because it’s a pure view although of course it’s affected by international capital flow which are all affected by the major central banks. But I do find that curve, being as flat as it is, very interesting and something to watch for.

FRA: Yeah could be partly also because on concerns with trade like with NAFTA, with the US and concerns there on discussion on the treaty, revising the terms of the treaty, which could be negative to Canada, and also on real estate, there’s been lot of international capital flow into Canada recently but theres been new measure in terms of taxation or tariffs, penalties imposed on foreign nationals/ foreign entities outside of Canada on the real estate market so it’s no longer as it was before so a lot of jobs recently created due to the real estate boom. So I think maybe those two concerns are bearing on Canada.

Yra: I know it’s worth discussing so you know everybody has ancillary reasons for why this, and what’s interesting because Peter brought it up from the (13:41- 13:42 inaudible) about foreign flow funds are we back to Bernanke argument about the surplus savings. I guess there’s still some people in the feds making that argument for the current state of affairs. That didn’t sit well with me in 2006 and it sits less well with me right now because it fails to take into account the real impact and the damage done by central bank policy but that’s an objective opinion on my part.

FRA: Yeah, exactly. So we talked about the Fed. But what about what about the Japanese central banks. There’s been some potential trends there in terms of the Japanese central bank buying less equities they bought a lot of the in the past and due to changes in the central bank policy, what are your thoughts on that and let’s start with Yra.

Yra: I deferred to Peter and I think he has a better sense of that. So Richard I’ll defer to Peter.

Peter: So what’s most interesting when the Bank of Japan decided to go to Yield curve control, it was there way of saying, “we already broke the Japanese bond market we need to start buying less, lets figure out another way of keeping the rate low. So they went from focusing on the price of money from the quantity of the money they printed. So they said let’s keep the spread the overnight rate and 10 year rate close zero give or take 10 basis points. And that worked in a sense that it allowed them to dramatically cut Q.E. Where they were running at peak 8 trillion yen a month to 50 trillion yen. Problem was that by destroying and flattening the yield curve to nothing, the you damaged profitability of the banking system and if your banking system is your transmission mechanism of your policy, you actually end up tightening via the easing because the banks are reluctant to lend because there’s no yield curve, well you are tightening they are now cutting back on what I’m hearing purchases of stocks. Well when they become dominant holder of Japanese stocks, you actually scare Japanese equity investors because you know it’s not sustainable unless the Japanese want to nationalise the Japanese stock market but I don’t think that’s on the agenda, you actually scare potentially buyers of Japanese stocks because you wonder and fear what’s gonna happen when the Japanese are done buying stocks the markets gonna fall. So their easing becomes into tightening while they still ease and I think that’s why Korota shifted the yield curve control to 20 basis points give or take from 10 but even 20 basis points really isn’t much from 10. So they have a major problem. The end game is somewhat over for the Bank of Japan. I just don’t know how they are gonna figure out a way of getting out of it.

Yra: Yeah I would agree. Peter has that absolutely right. Their QQE, is they refer to it of course, it was quality and quantity as they were buying stocks. I think they have been under buying for a long time that’s why I wasn’t so surprised when they made that announcement in the initial reaction was a quick shutoff of in the equity and a quick reality in the Japanese Yen. So but I don’t think it really was that great of a surprise to the market because they’re not very transparent. It was like watching the Yishibi who would publish where they were at the end of every week and you can kind of follow and map that you knew exactly what they were buying according to the capital keys. The Japanese have really been very secretive here and I think Kuroda has followed. I agree with Peter and I think it’s a terrible policy and I think he was able to do what he was to do because he could do it out of the heels of again Bernanke. I respect Jay Powell and it’s interesting to hear these views but the United states does have a global fiduciary and when it fails, it does things to creates havoc in the system and then everybody else follows as it goes (18:40-18:42 Inaudible) their doing it and (Inaudible) okay I’m going to do this here. So we’ve gone to preposterous measure of central bank activity in the world and I think the first rumblings in the emerging is some of the coming price that’s going to be paid. I can’t tell you when, I wish I could cause then I could retire and then I could do these podcast fulltime. But I think it’s coming to watch out for and I think Peter is picking up on that. With the Bank of Japan, I think they have gotten themselves into a terrible situation.

FRA: Yes and Peter what about the Japanese currency and the last couple of months. It seems to be increasing or strengthening at even faster rate than the US dollar?

Peter: It’s amazing it’s like a conundrum. I mean when you look at the Japanese monetary and fiscal situation you tell yourself, “Why isn’t it 250 instead of a dollar let alone 110 or 112? But I think the recent rally is strictly due to the change in Japanese policy in terms of the yield curve control and continuing to trim Q.E. It’s really as simple as that. Where the end goes from here is, you could flip a coin. As I said on paper, it deserves to be a lot weaker but considering how the US has been handling, its finances. The dollar should be that much stronger than the Yen. So I think what the end results is that printing currency and weakening your currency is not necessarily the pathway to higher inflation. And that was the goal of Bank of Japan was to create 2% inflation even though it’s completely unrealistic benchmark, particularly in a country that had a shrinking population and a growing, aging population that needs to save and really spend less therefore, another reason why you are not going to get the higher inflation. So, here we are with their balance sheet that is almost 100% of their GDP and they are the top 10 holders, 40% of Japanese equities listed on the Nikkei and the CPI number, which comes out tonight, core CPI or core core CPI ex energy and food, is expected to be up all 3/10’s of the year. Astonishing!

FRA: And moving from Japan to China, Yra you referenced the Financial times news item and which it was stated that China’s banking regulator has ordered to boost lending to infrastructure projects and exporter as the government seeks to bolster economic confidence on the eve of a new rounds of trade negotiations with the US. Your thoughts on that?

Yra: Well my thoughts are that is when I wrote that there was a weekend article which I thought was very important article and I did exactly what I thought it would do which is that is coppers and everything that has been down been up all this week. Including everyone was bullish the dollar but this was done to assuage the immediate pressure. I don’t think the Chinese have as much room as they would believe but I thought it was a very interesting switch because they are evidently a little bit nervous about too much slowdown too quickly in the Japanese economy and I know Peter has been watching the Chinese bonds are also approaching are approaching the very low levels they are almost as low as the US ten year. In a country if we believed in numbers, you know over 6% GDP growth. There getting a little worried and their worried about how far Trump’s going to take this Tariff issue? So I thought that was done in way to politically assuage some in the White House and hoping that they would be able to control more of the dialogue between the two and soften some of the rhetoric. It was interesting. Another thing that took place, today or yesterday, the German foreign minister. You know, lets hold off for a bit. Peter you go with China then I will come back with the German foreign minister thing cause he did some interesting things.

Peter: China’s in this tough spot where they acknowledge the success of credit groups that has led to so many imbalances in their economy on top of the massive leverage ratio and that’s why they have been pushing to try to at least bring lending on to bank balance sheets and off the (Inaudible 23:45) outside but at the same time, they don’t want to suffer big decline in GDP growth and they still want the 6.5% type growth and you throw the tariffs in that is a threat to growth which causes another policy conundrum because they want to slow credit growth but they want to speed it up to offset the tariffs. How this plays out is again going to be a mystery because China’s economy overall is a mystery. I think over time, slowing credit growth and trying to maybe privatize is the wrong word but continuing to shift their economy to more private sector dependent area and business’s are a good thing and actually bullish in long term but how they manage this in the next year or two is going to be extraordinarily difficult particularly if Europe is going to slow at the same time because of their own challenges and the end of QE and the Europe is a huge customer there and how they manage further relationships with the US. Now today, delegation comes to US to discuss trade and I’m beginning to now wonder whether China’s saying you know what, we’re not giving in and we’ll wait after the election, the midterm election in the US, because when the democrats takes the house when Trump is going to have less leverage, and maybe we cannot give in as much as he wants us to do. So where the Chinese economy goes is will be how much do they dig in and I think they at least they show some interest in digging in and not giving in to what Trump wants and you throw in this whole Michael Cohen thing and I think that’s kind of irrelevant for the whole US economy and markets and they take this as a sign of vulnerability, which gets them into digging even more. We’ll just have to wait and see.

FRA: Back to the German foreign minister Yra?

YRA: Yesterday, German foreign minister. Hold on one second…It was the only thing I was interested in reading today (Inaudible 26:01- 26:03) it was out and I recently saw this story and nobody really talked about it but discussing it that Europe and others need to break away from the strangle hold of the United States especially office for Foreign Asset Control which is under the US treasury and its ability through sanctions and other mechanisms to control, of course, fund transfers globally which is what the Russians and others, the Iranians, the Turks yelling about, because the US treasury really has the power to affect your ability to move money and the German foreign minister came out and said, they have to be get ready to move beyond this. I thought it was interesting that he came out with that following the Putin and Merkel meeting over the weekend. And Merkel actually this morning came out and supported the article (Inaudible 27:00 27:01) and she came out to supported the foreign minister and those views and it’s really all directed at trying to circumvent the ability of the Swiss system because its price and dollars and the United States has disproportionate amount of power to control a lot of global events because of it. So they want to circumvent it. I think that’s what the Chinese would ultimately like to do and I think that’s what the Russians would really like to get themselves out of which is why I talked about these sanctions they want to remove it is a matter of what negotiating power Putin has with the Trump White House and I’m not talking about the more sorted events, I’m talking about the ability for the Russians to be able to influence and dramatically influence the events in the mid- east. So this is all coming together at an interesting time and I think it’s really a sense of push back against the US “bullying”, as I think the world would say, in regards to foreign exchange flows. This is really nothing new. It really goes back to the 50s and 60s when the French were complaining about the same thing for the different reasons that the US had way to much influence because of dollars rolls reserve currency. But I think this is important and I think it needs to be on everybody’s radar screen to pay attention to.

FRA: Peter any comments on that?

Peter: I agree with Yra, it’s definitely something to watch. All the goings on with the emerging markets right now is important to watch. It’s no coincidence that just within a 6 month time frame that Turkey, Argentina, the time bonding market, the short (Inaudible 28:53) trade is blowing up. The liquidity flow is going the other way and monetary tightening is taking hold and stuff beings to happen and accidents begins to happen and things get more exposed, investors become more discriminating, they become less tolerant to problems. I expect more of these accidents as the months and quarters progress. The questions is how insulated or how (Inaudible 29:18) U.S economy gets impacted by that.

Yra: I think, Richard, that the world is more concerned now because they’ve seen a president or a political leader in the United States who is trying to change the entire narrative of the last 60 years anyway and their going, “wow, we really made our selves sub-servient” because of our needs for dollars but when they see the ability to use this as political leverage, I think the world is very nervous about this important piece of discussion

FRA: Yeah and finally on that relating to the emerging markets, if we look at countries with high risk for currency crisis, like Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina, Turkey, what do you make on Turkey president Erdogan and the possibility of capital controls? Yra?

Yra: Well I think that’s a great possibility. I know everybody you hear all these what I call a (inaudible 30:34) analyst who come out and that’s not going to happen because he’s a rational actor and why would you do that? I would be very careful with Erdogan. First off, he’s very good friends and very close to Mahatir Mohammed, well now he’s was back in prime minister of Malaysia, but back in 1997, 98, during the Asian contagion, Malaysia did put on foreign exchange controls in September, I believe 1998, and it actually aided them and they did it by thumbing their nose at the IMF so everybody else is running to the IMF and dealing with well we’ll borrow money from you but the IMF of course could lend playbook was raise interest rates and cut the spending to reign in the deficit so your basically forcing yourself a severe economic slowdown, Malaysia said no. They went to foreign exchange controls where they tied up money for a longer period of time and if you would do this now, I think first of all, it would cause a lot of havoc in Europe cause so many European banks are involved in Turkey then other banks because of the close ties but the foreign exchange controls are something that this global market really fears because anything that ties up, this whole market is built on the free flow of capital so a country of Turkey size with that much amount of debt, I think that will cause negative reverberation throughout the system and setup a very potential negative feedback loop as far as global liquidity and I think that could really cause problems something that you would have to watch out. Erdogan is, you know, he’s first off foremost curious about Erdogan so I think we should be very attentive to this.

FRA: And Peter?

Peter: I agree with Yra because you can imagine being an emerging market and investor in Turkey and all of a sudden you can’t get your money out. Well you’re going to sell everything you can to offset that so the capital flight from other emerging market could be rather extreme. Now Turkish government has it that there not going to go there but it doesn’t mean they’re not going to change their minds tomorrow. Yra mentioned the precedent that we saw in Malaysia 20 years ago so it would definitely cause a lot of problems and this is all related to excessive leverage, a lot of it at the corporate level, a lot of it dominated in dollar, which is not the currency they collective their revenue in. A classic repeat of this search for yield and okay give me zero interest rates then get me yield. If I can lend money to Turkey for 8%, I’ll take it. Classic search for yield that is now causing a rethink and as I said earlier, a more discriminating view. (Inaudible33:43) Investors when interest rates rise, and monetary tightening picks up.

It’s like we keep repeating this same movie over and over and over again. Just some different colours and different acts the same underlying themes. Over and over and over again in the history of financial markets.

FRA: Yes exactly and we’ll end it there. Great insight as always gentlemen. How can our listener learn more about your work? Yra?

Yra: I blog at the notes from underground and all the podcast I’ve done with Peter, and Financial Repression Authority is a good way to get the discussion out there and I’m very happy to have this opportunity to do this because I think investors needs to hear about these things that you can’t just put on rose coloured glasses and oh earnings are forever and going up and it just doesn’t work that way. Peter just reminded us that things are changing and you have to be attentive to them and whether you agree or disagree, you have to put it into your quiver and at least have the knowledge of it because when these things happen, and it’s not that there not going to happen, it’s just everything else in life is about timing and understanding it. So I just push the idea of understand it so that what you will find in my blog, notes from the underground.

FRA: Yes exactly, and Peter?

Peter: So you may read all my work at the BoockReport.com and if you’re interested in asset management and other financial planning, and you can check us at Bleakley.com.

FRA: Great! Thank you very much gentlemen! Thank you!

Yra: Thank you Richard! Peter good talk with you!

08/10/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: John Browne & Yra Harris See Massive Stress Building In The Financial System

08/10/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: John Browne & Yra Harris See Massive Stress Building In The Financial System

07/25/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Doug Casey On Precious Metals, Cryptocurrencies and Agriculture

07/25/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Doug Casey On Precious Metals, Cryptocurrencies and Agriculture

07/12/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: Yra Harris & Peter Boockvar On Escalating Trade Wars & Global Economic Risks

07/12/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: Yra Harris & Peter Boockvar On Escalating Trade Wars & Global Economic Risks

06/07/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: Ronald-Peter Stoeferle And Yra Harris On Gold And The Emerging Chaos In Europe

06/07/2018 - The Roundtable Insight: Ronald-Peter Stoeferle And Yra Harris On Gold And The Emerging Chaos In Europe

06/07/2018 - Emerging Markets Are Begging The Federal Reserve To Stop Shrinking Its Balance Sheet

06/07/2018 - Emerging Markets Are Begging The Federal Reserve To Stop Shrinking Its Balance Sheet

Central Bank of Indonesia Governor:

“We know every country must decide their policy based on domestic circumstances but look, you have to take account of your actions and the impact of your actions to other countries, especially the emerging markets.

There are three global players that impact the future of interest rates and exchange rates. Now it’s only the U.S. .. That’s why the U.S. and the dollar are king. But next year if Europe starts normalizing, Japan starts normalizing, then I don’t think the U.S. or the dollar will be the only king.”

06/06/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Jayant Bhandari On The Risks Of A Stronger U.S.$ And Rising Rates On Emerging Markets

06/06/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Jayant Bhandari On The Risks Of A Stronger U.S.$ And Rising Rates On Emerging Markets

FRA: Hi welcome to FRA’s Round Table Insight .. Today, we have Jayant Bhandari. He is constantly travelling the world to look for investment opportunities. Particularly, in the natural resource sector. He advises institutional investors about his findings. He also worked for six years with US global investors in San Antonio, Texas, a boutique natural resource investment firm and, for one year, with KC Resource. He writes a lot of a number of publications including liberty magazine, the MC Institute, KC Research, Acting Man, International Man, Mining Journal, Zero Hedge, Little Rockwell, Frasier Institute and many others. He is contributing editor of the Liberty Magazine. Welcome Jayant.

JAYANT: Thank you very much for having me, Richard.

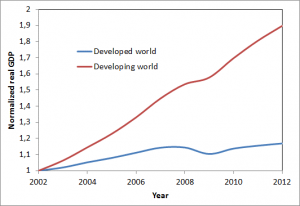

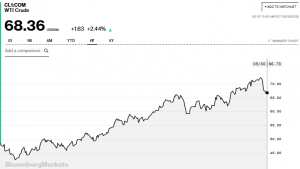

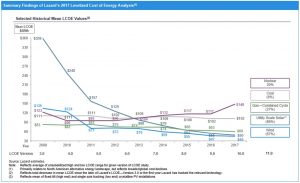

FRA: Great. I thought today we’d do a focus on the plight of the emerging markets, and you have graciously come up with a number of charts that can help form the basis of the discussion. We’ll make these charts available through the link on the website. But, yeah, I wanted to focus on what’s happening in the emerging markets considering the trends in oil prices, in the US dollar, interest rates and what they have done in terms of investing in energy in particular, what they have not done is probably a better way to put it. Just wondering your initial thoughts on that to get the discussion going.

JAYANT: What happened, Richard, was that from 1995 onwards for almost 20 years, emerging … What are now known as emerging markets did grow very nicely. They have grown by about 100% between 2002 and 2012 according to one of the charts that I sent you. While this growth was an extremely good growth for the emerging markets, from the base that they were starting at, the problem is that the growth rates of the emerging markets have been falling consistently for the last 10 years. Now, if you pay closer attention to what’s happening in sub-Saharan Africa, the growth rate has fallen to only 1.4%. Now, when growth rate … Economic growth rate is only 1.4% and population growth rate is 2.8%, you actually now suddenly end up with a negative growth rate which is -1.4% per capital for sub-Saharan African.

Growth rates in the third world are falling and in case of sub-Saharan Africa it is negative now—while there is still 1.4% GDP growth rate, population growth rate is 2.8%. The net effect is negative growth rate on per capita basis.

Today, US 10-year treasury yields are inching towards around 3%. WTI crude has gone up from US$48 a barrel to US$68 today.