does some great reporting, it can slant reader perceptions by leaving out links which would allow the reader to gain a fuller perspective of the authors intent since a clip taken out of context, can be extremely misleading. Having said this as a full and responsible disclaimer, it seems clear what Citibank’s Willem Buiter has concluded lies ahead.

“Helicopter money drops (what else?)”

Our conclusion is that, in a financially-challenged economy like the Eurozone, with policy rates close to the ELB, and with excessive leverage in both the public and private sectors, balance sheet expansion by the central bank alone may not be sufficient to boost aggregate demand by enough to achieve the inflation target in a sustained manner.

This is more than an academic curiosity. Japan has failed to achieve a sustained positive rate of inflation since its great financial crash in 1990. The balance sheet expansion of the Bank of Japan since the crisis has been remarkable but ineffective as regards the achievement of sustained positive inflation and, since 2000, the inflation target. The balance sheet of the Swiss National Bank has expanded even more impressively, again with no discernable impact on the inflation rate.

* * *

We do expect the ECB’s asset purchase program will expand considerably further, with the Eurosystem’s balance sheet reaching €4,000-4,500bn over the next year or two. But we doubt that even this will be enough to achieve the inflation target of close to but below 2% on a lasting basis. It might take even greater ECB balance sheet expansion to achieve the target.

But the larger central banks’ balance sheets get, the louder will become the voices of those that criticize the power vested in unelected and mostly unaccountable central banks. In addition, it is worth remembering that the laws and regulations that underwrite and circumscribe central bank actions were written at a time when their current range of actions, let alone the potentially even larger future ones, seemed exceedingly unlikely and maybe even (in the case of the ECB) inconceivable. Political concerns likely played a role in the SNB’s decision to rely less on its balance sheet and more on negative rates when managing its currency (and indeed allowing a sharp appreciation of the Swiss franc and greater exchange rate volatility). The ‘Audit the Fed’ movement is likely to be followed by ‘Audit the ECB’ movements and eventually by explicit limits on central bank actions as their balance sheets grow to politically unacceptable levels. We do not say that moment is near, but to dismiss the idea that political limits to the size of the central bank balance sheet exist seems naïve.

Moreover, even if the ECB were to expand its balance sheet sufficiently to achieve the inflation target in the next few years (say, to €5tn or €6tn), the monetary policy toolkit would then seem to be rather empty, with little option for stimulus if and when the next downturn hits (as it inevitably will). Experience teaches that downturns do happen – either for internal or external reasons – and sometimes happen when output gaps have not been closed. What happens then? Draghi’s answer seems to be: perhaps a balance sheet expansion to €10tn or €15tn. We are doubtful that such a course of action would be both perceived to be politically legitimate and economically effective.

* * *The case for helicopter money is therefore partly to ensure the euro area (and some other advanced economies) reflate powerfully enough to escape the liquidity trap, rather than settle in a lasting rut of low-flation and low growth, with “emergency” levels of asset purchases and interest rates becoming the norm.

* * *

In orderly markets and with the policy rate at the ELB, the central bank can talk loudly, but on its own – without the fiscal support required to turn its monetized balance sheet expansions into helicopter money drops – it carries but a small stick.

* * *

If, as seems possible, the ECB will increase, in H1 2016, the scale of its monthly asset purchases from €60bn to, say, €75bn, and if these additional purchases are concentrated on public debt, the euro area will benefit from a ‘backdoor’ helicopter money drop –something long overdue.

CONCLUSIONS

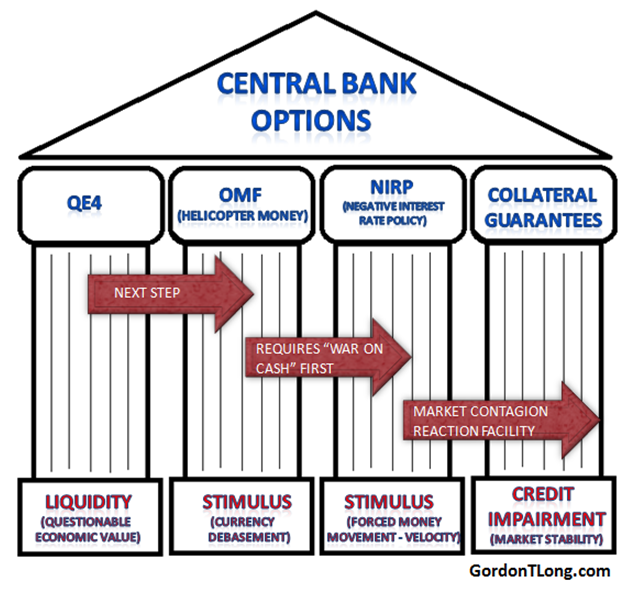

This supports FRA’s views on the coming policies on OMF (Helicopter Money).

12/27/2015 - CITIGROUP’S CHIEF ECONOMIST SAYS Government to pursue the only option left – “Helicopter money drops (what else?)”

12/27/2015 - CITIGROUP’S CHIEF ECONOMIST SAYS Government to pursue the only option left – “Helicopter money drops (what else?)”