FRA: Hi, welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight .. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith: America’s philosopher, we call him. He is the author, leading global finance blogger and he is the author of several books on our economy and society, including “A Radically Beneficial World: Automation, Technology and Creating Jobs for All”, “Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change” and “The Nearly Free University and the Emerging Economy.” And recently, “Pathfinding our Destiny: Preventing the Final Fall of Our Democratic Republic.” His blog OfTwoMinds.com is one of CNBC’s Top Alternative Finance Sites. Welcome Charles!

Charles: Thank you Richard, it’s always a pleasure!

FRA: Great, I thought today we do a focus on the Federal Reserve. That’s been in the news, you know, quite heavily in recent weeks and even today, we are talking on Wednesday July 10th here.

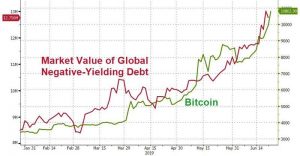

Just wanted to do a focus on how everybody has an obsession, the market itself has an obsession with the Federal Reserve as being essentially the sole driver of higher valuations. You know, is this healthy or not? It is essentially financial repression taken to an extreme. I just did a podcast yesterday between David Rosenberg, Yra Harris and Peter Boockvar. All three, who frequently appear on CNBC and Bloomberg. And we had a very similar discussion on the very similar theme. Even, David Rosenberg thinks that it is going to be very extreme on what the actions the Federal Reserve would take. Essentially going towards zero interest rates. More and more (Inaudible 1:58). And ultimately, debt monetization where the Federal Reserve buys whatever debt that is issued by the Treasury.

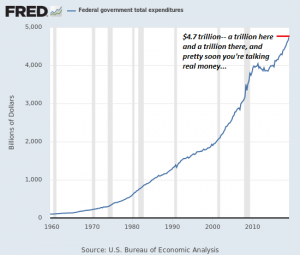

And so, on that theme that you have graciously provided some charts. One of which, is showing how the Federal government expenditures been going through the roof asymptotic and resulting in deficit spending essentially.

So, that will all continue, but essentially the message is there that the Fed is there as a backstop. It’s there to do the monetization, outright monetization of whatever debt is needed. Your thoughts?

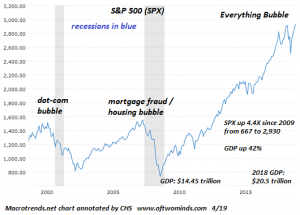

Charles: Yeah, thank you for that excellent summary of this situation Richard. I guess my first response is just to go back a bit in history and I have a chart here of the last three bubbles in a S&P 500.

Going back to the 1990s dot-com bubble which burst and then the mortgage housing bubble in the late 2000s which burst. And now, the so-called Everything Bubble. And what strikes me about this, as you say, single-minded obsession with the Federal Reserve Policy. Like, what’s the latest easing going to be to push valuations higher. That strikes me as what happens at the top of equity bubbles, right? Because, when the market seems to be relying on one driver and (Inaudible 3:38) solely on that. That seems to mark a top and when I think back to the 1999 NASDAQ bubble and the dot-com bubble, there was of course the underlying sense that the internet was going to be growing for decades and so, you know, you couldn’t go wrong on investing in internet companies. But there was also like an almost comical obsession with something called the “book-to-bill ratio” which was a measure of orders compared to current billings in the semi – conductor industry. And the semi – conductor industry was part of a proxy for the entire tech sector at that time. And so, you see these huge swings in equity valuations across the entire tech sector, not just semi – conductors based on this week’s book-to-bill ratio.

And so, it was laughable even then, how focused the market was on one indicator, right? Which as valid as it might have been in some certain circumstances, it was like the whole market was being swung up or down by this one indicator. And then in the mortgage housing bubble of mid-late 2000s: 2005, 2006, 2007. Then we were told, well you know, housing never goes down and well people were interested in what the Fed had to say, in terms of the effect on mortgage lending rates and so on. The obsession was really with how fast real estates appreciating this (Inaudible 5:10). And so, I guess that’s part of what I feel is it feels extremely fragile here is this obsessive concern with Fed Policy as the only thing that could possibly push markets higher. So that means higher profits, higher sales, innovation, you know, higher wages. It’s like none of the things actually make a healthy economy are of any concern and that should trouble us.

FRA: Yeah, it is and it’s almost perverse because as you can see in the announcements of labor statistics, for example, the market is keenly looking to those statistics as a driver of monetary policy and ultimately affecting equity valuations. So, that if the labor statistics are bad, then there is a sense that the Fed will be pumping more, easing more, so therefore the markets go higher. On the other hand, if the labor statistics were good, then that would translate to “Oh no, the Fed is not going to give us that drug.” And so, we won’t get it, so therefore equity valuations go lower. So, it’s just totally crazy and perverse. Your thoughts?

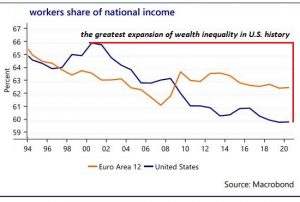

Charles: Yeah, and I am glad you brought that up because in terms of labor statistics and whether wages and earned income is rising or not, I have a chart here that shows workers share of the national income.

And what’s really striking is it’s been in decline since the (Inaudible 6:50) 21stcentury here in the U.S. And so, in this period in which the Federal Reserve and other central banks have made the greatest expansion of quantitative easing and the greatest expansion of central bank balance sheets and massive financial repression to keep rates near zero. It hasn’t benefited people with depend on earned income which is the vast majority of people, right? I mean certainly the bottom, say 90% of households, store their wealth based on their income. Not on, you know, their equity ownership. And so, it’s been a disaster for the bottom 80-90% of households and it’s only benefited the top 10% of which the vast majority of that is actually goes to the top 5% and top 1%. So, it hasn’t benefited the economy as a whole or society as a whole. So, you’re right, it’s just massively perverse.

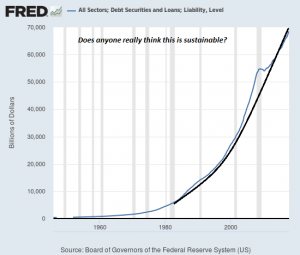

FRA: And even then, it’s very fragile. The whole system, as you can see on your chart, for all sectors; debt securities and loans; liability, level is that little blip in the financial crisis that just seems to be a hiccup, but caused massive financial crisis globally and things are just getting worse.

We are going higher and higher on a swimming pool plank with less and less water and more and more instability. It’s just crazy. Your thoughts?

Charles: Yeah, I’m glad you brought that chart up because this is total systemic debt, basically, you know, public and private. And it’s pushing 70 trillion in the U.S. And GDP is around 21 trillion, so it’s over three times GDP. And what’s really frightening is the rate of increased, you know, that it’s from that little blip in the 2008 – 2009 crisis. Total debt was around 55 trillion and now it’s 70. So, we have added, you know, 15 trillion dollars very quickly and it doesn’t seem to be any reduction in the rate of that debt accumulation. And this rapid rise in debt across public and private is sort of mirrored by the rise here in Federal expenditures, which also this chart I have here from St. Louis Fed database shows Federal spending. It also had a little hiccup, you know, right after the recession. And it resumed very fast increase, so the Federal government is spending 4.7 trillion a year and taking in roughly a trillion less in revenues. And so, here we are floating another trillion a year in Federal debt in so-called “good times.”

And then of course, we would have to add in state of local government are also borrowing a lot of money, in terms of municipal bonds (Inaudible 10:29) and that kind of debt. And then there’s private and corporate debt. So, is this a healthy economy that’s so dependent on debt and therefore dependent on central banks dropping interest rates. How would you say, in terms of financial repression, everybody knows the positive effects of the Federal Reserve dropping interest rates, right? But what about the negative effects? Nobody seems to talk about that. I mean there are negative effects, right?

FRA: Yeah, exactly. It’s in all different aspects: the economy, the financial markets, social implications, widening income, wealth inequality, resulting from all this. And we’re rapidly approaching what central banks can do or have the capability of doing these other charts as well that can show how more and more debt is needed for an incremental increase in economic growth and that is getting bigger and bigger. More and more debt needed for just a slight amount of economic growth and that’s in the economy. And then in the financial markets, if we look at the bond market, more and more of the major central banks are getting into the situation where there they may be the only buyer, the last and only buyer. And, you know we look at, for example, bank of Japan that’s been in the case already for quite some time. European central bank is essentially is there now and the Fed is approaching that situation as well. And those areas are pretty dire situation. If you have the point where only the central banks are buying, basically there’s no market for it. Your thoughts?

Charles: Yeah, it’s interesting. I call that mechanism “a perpetual motion machine.” In that, you know, the Japanese model and what you referenced earlier in our talk that David had said when the central banks are going to monetize debt, then it’s like a perpetual motion machine because your national government can borrow a trillion dollars and spend it. And then your central bank buys those bonds and they basically vanish without a trace into the central bank balance sheet. And there’s no cost to society, in the sense that the Federal Reserve returns much of its income to the Treasury. So, it looks like, well there is nothing here? I mean, why couldn’t the Federal Reserve just go ahead and monetize 2 trillion dollars a year in deficit spending and let the balance sheet go from 4 trillion to 20 trillion or 30 trillion. And of course, a lot of people are looking at Japan as the model for this, as they more or less gotten away with this. And then everyone says, well you know, the train is still run on time and Japan is still a wealthy nation and everything works. And so, why not monetize debt and just let your balance sheet go crazy? Who cares? And so, it’s hard to answer. It’s hard to come up with a reason why that doesn’t work because Japan seems to be proving it does work.

FRA: Yeah, I mean, essentially there’s the two-lever situation with debt, right? So, that you have the quantity of debt and the interest rate. So, as the interest rates have gone down through financial repression, it’s allowed governments to go on a debt binge essentially for more and more debt. Much more debt now than we were at the financial crisis, for example. Problem with that is that is very high levels of debt and as the interest rates creep up ever so slightly, it becomes higher and higher servicing costs and that could get out of hand. So, you could be boxed in, you know, in terms of what governments can spend. Your thoughts on that?

Charles: Yeah, I think that’s a great point Richard. And of course, in Japan, every few years I try to keep track of what percentage of their central government’s tax revenues go to just pay the interests on their enormous sovereign debt. And I believe it was 40%. Now, this interest rates are basically .01 or less, right? I mean, you couldn’t get anything closer to zero than Japanese sovereign debt. And yet, it’s already consuming 40% of their tax revenues. I’m just saying that as an example of the mechanism you are describing, that eventually even at a tenth of one percent interest, you get boxed in because you are just servicing that debt. Makes it more difficult to take care of the rest of your social and government spending. And of course, the other downside is that no one could earn any money safely, right? The only way that anybody could earn money is by speculating that the central bank is going to lower interest rates below zero. So, that your bond that you bought is paying .01% will go up in value because now that the rate is minus .5% or something.

But you know, in terms of like safety and safe returns on investments for insurance companies and pension funds and so on, that’s also been basically destroyed, right? I mean, for people that are much younger, they may not remember that back in the 70s, it was a regulation that savings and loans would pay five and a quarter percent interest on your savings. And so, that was actually fairly hefty. And now of course, it’s impossible to earn five and a quarter percent safely. You know, you’re taking on enormous risks in buying junk bonds or corporate debt to get that. And so, I think that’s another element of fragility, you know. As well as the size of debt, in getting boxed in by the debt. We’re also boxed in because everyone has to gamble now in highly risky dangerous asset markets, in order to earn some sort of return.

FRA: It’s crazy. It’s unsustainable and where do we go from here? What is the way out? Another theme yesterday that was discussed is essentially inflating. There’s only essentially one way is to inflate the way out to make that burden of debt less burdening by increasing the inflation rate to much higher levels. Your thoughts?

Charles: Right. That’s what a lot of us have been anticipating and of course, we know for a variety of reasons governments understate inflation. We think the real-world inflation is, as you and I discussed many times, running more like 6 to 7 to 10%, instead of the 2.1 or whatever the official rate is. But yeah, we have all been anticipating that and I think what’s interesting is there’s got to be a deflationary element in the system that has been offsetting the inflationary impacts it should be registering, in terms of deficit spending and money creation and so on. And so, you know, it could be that like say, going back to Japan as an example that deflation is a factor in Japan because their workforce is shrinking. So, there’s less consumption and there’s fewer drivers to push up real estate and equity. So, there’s just fewer workers. And so, then you get deflation in consumer prices and then in assets. You also have a huge overhang of that debt from the Japanese bubble of the late 80s. And so, as loans are defaulted and get written off, then that’s also deflationary.

So, it makes me wonder what happens when you don’t have any deflationary impacts. Then we might get an inflationary shock, if say, the Federal government decides to pursue modern monetary theory ideas of huge stimulus programs: universal basic income. And, you know, we can (Inaudible 20:05) about numbers in general. It’s like, maybe, a limited universal basic income would probably add about a trillion to Federal spending and it’s pretty easy to add a trillion more in infrastructure and other fiscal spending stimulus. So, if you are going to create and push out 2 trillion a year in a 20 trillion-dollar economy, I think maybe we will finally get inflation.

FRA: Yeah, and if you look at one other great thinker in the Austrian School of Economic tradition, I was talking with Ronald-Peter Stöferle of incrementum a couple weeks ago. He wrote the book on Austrian School Investing and he pointed out that Murray Rothbard has the view of the three phases of inflation. He was one of the great thinkers in the Austrian School and he says first we look at the monetary inflation. We had that. We had a lot of that. That then goes into Asset inflation. Obviously, we had that and still have that. A lot of that. And then, the third phase is consumer price inflation. Eventually, all comes into consumer price inflation. So, that 8-10% a year, roughly, where if you look at the Chapwood Index of inflation more accurately measures inflation than any other index, including government statistics that indicate 8-10% per year in inflation in most of the U.S. cities. That is likely to get higher as time goes on. Your thoughts?

Charles: Yeah, absolutely. I’m glad you brought up Rothbard’s work because a lot of people I think have been lulled into a false confidence that we can basically create essentially endless amounts of money or credit, and there’s never going to be an inflationary impact because we gotten away with it for 20 years. Or, in the case of Japan, 30 years. But that may be a false assumption. You know, I want to mention a social impact here. When we talk about finance, we have to remember (Inaudible 22:32) there’s a social impact to this kind of financial repression of jacking up asset valuations with quantitative easing and super low rates. And so, I spend some of my time in the San Francisco Bay Area. And, as we all know, there’s many real estate bubbles, where you are in Canada and Vancouver as well. Many West and East Coast cities in the U.S. are reaching absurd levels of housing valuations. And so, approximately 5% of the population in the San Fransisco Bay Area can’t afford houses there. And of course, this is a region with very high incomes and say, a top 5% income in the Bay Area is, I believe it’s $400,000. Where in the rest of the U.S., is more like $250,000 or $300,000. So, you have to make really enormous sums of money to afford a bungalow in the Bay Area. And so, what’s the net result of this socially? As well as economically?

One social result was just a poll that was published in the San Jose Mercury News that said, “60% of millennials in the San Franciso Bay Area (now there’s people around 30 or under) want to leave or plan to leave the Bay Area in a few years.” Because there’s just no point in staying in a place where you have no future. Where you are going to be struggling to pay the rent. And that’s it. You will never afford a house. And, they had a young couple that (Inaudible 24:21) and saved and worked two jobs and so on. And bought, like a little bungalow for $700, 000 a few years ago. And their quote was worth thinking about because they said, “We are working at a 150% to maintain a lower middle-class life.” In other words, it wasn’t like they were really getting ahead. So, that’s the social costs of central banks pumping up assets, in order to please the current owners of all these assets, right? And, I think that’s going to cause a social disorder on a massive scale at some point.

FRA: Yeah and also, I have a feedback loop into the whole problem making it worse. Because if you got this effectively brain train happening, as well as some level of wealth train as well. You know, as the millennials believe from some economic activity representing that. And this not just in the Bay Area, I see it here in Toronto. There’s a lot of articles and charts showing it for all over. In particular, by the way with Chicago Illinois, what’s happening there the millennials will not likely be as idealistic as they have been portrayed. But they will believe that it will begin moving out. And this will make the whole problem worse, because then there will be more draconian, financial repression, higher levels of taxation and just making the whole thing worse and so on and so forth. And cause more and more people to drive out. So, that social problem and effect that you just mentioned could get worse. Your thoughts?

Charles: Yeah, no absolutely. I think that’s, as you say, a feedback loop. I just got an email from a reader in Chicago, said she mentioned Chicago, and he said his property tax had gone up by 48%. Partly from valuation, but partly from higher rates. And so, he says, “I don’t know how many people can withstand this kind of increase.” And then, you know, the Federal Reserve we were talking can monetize sovereign debt, right? The Treasury could issue a trillion in bonds and the Federal Reserve can buy that. But what about real estate? There’s roughly 15 trillion in real estate, private real estate in the U.S. Is the Federal Reserve going to start buying houses in Chicago to prop up the house values there? And so, in other words, I guess my point being that the Federal Reserve and other central banks have a pretty easy mechanism for propping up equities and bonds. Because they can just monetize the bonds to debt and they can just print money and buy the stocks, right? As part of Swiss Central bank and so on.

But the vast majority of people’s assets in the middle-class are in their house. And so, if the housing bubble pops, then what’s the Federal Reserve going to do? Well, they are going to lower interest rates to try to create negative mortgages. Where if you take out a mortgage, you end up getting paid. I’m not sure how that’s going to work. But I guess my point is, I think we’re really pushing on a string because you can’t prop up all asset bubbles everywhere without, basically as you say, destroying any notion that there’s a market there at all.

FRA: And so, where does this all end? I mean, it seems like a lot of doom and gloom. And maybe, we could end on a positive note from your recent book, “Pathfinding our Destiny: Preventing the Final Fall of Our Democratic Republic.” What ideas and concepts that come from that book that can apply to what we have discussed, in terms of positive way out or potential positive outcome? What changes need to be made to the Federal Reserve, to the economy, financial markets in your view?

Charles: Yeah, well, thank you for that question. I think the core concept that a lot of people realize or share the idea that this is the way forward would be: decentralize capital, decentralize banking, decentralize political power and so, that would render the economy and the financial sector much more flexible. And so, you could have in Nassim Taleb’s conception, you would have a more anti-fragile economy and financial system. Because you would have a lot of variation in there because it was free to be a market again. And so, if we had let’s say, a thousand banks instead of 5 or 6, then that would be a way forward I think. And if the Federal Reserve, it is almost impossible to imagine, but we could at least dream of it returning to its original purpose which was to simply to be the lender of last resort in financial panics. Where there would be liquidity crisis, if the Federal Reserve could return to that role and stop being the prop under equity values.

We could restore the flexibility that’s inherent in markets and decentralize political and economic control. Because then you could respond to local conditions and losses when they are created can be taken without putting the entire system at the risk of collapse, which is what happens when you centralize capital control and banking. And so, that’s really the ultimate risk we created here is we centralized everything and made it much more fragile.

FRA: Well, great insight and how do we possibly get out of this? From your recent book, how can I listen and learn more about your work Charles?

Charles: Yeah, visit me at OfTwoMinds.com. There’s free chapters of all my most recent books, so you can read the first couple of chapters for free and see if they are of any interest. And all my archives and essays are free.

FRA: Great. Thank you very much Charles! We’ll do it again.

Charles: Thank you Richard!

Disclaimer: The views or opinions expressed in this blog post may or may not be representative of the views or opinions of the Financial Repression Authority.

07/16/2019 - FRA – The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith on the Market’s Obsession with the Federal Reserve

07/16/2019 - FRA – The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith on the Market’s Obsession with the Federal Reserve