FRA: Hi. Welcome to FRA’s RoundTable Insight .. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith. He is an author and leading global finance blogger and America’s philosopher – we call him. He’s the author of nine books on our Economy and Society including A Radically Beneficial World; Automation, Technology and Creating Jobs for All, Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change and the Nearly Free University in the Emerging Economy. His blog oftwominds.com has logged over 55 million page views and number 7 on CNBC’s top alternative finance sites. Welcome, Charles!

Smith: Thank you, Richard! Always a pleasure to join your program.

FRA: Great. I thought today that we’d do a discussion on what you actually wrote about recently: the tension between the public sector and the private sector. In particular, between public pensioners and the population that pays for that – mainly in the form of property taxes and other fees. This is happening all over North America – this growing tension. Likely to result in a growing pension crisis across the continent and also globally too. This is a global problem as well and just wondering about your thoughts initially on that from your recent writings.

Smith: Right. Thank you, Richard. I think it has been a topic that has that has been suppressed by the mainstream media because there is no easy solution. In other words, the authorities in charge of the pension funds have tended to down-play it by claiming they’re going to make it up from very high returns on capital and other kinds of peen less means but the reality that is now becoming visible is that the public pensions have to be funded at rates that require the cutting of public services. So, there is a seesaw here – that the more money that is put in to the public pension funds to build up their capital to minimum levels then the less money there is available for public services. It is a win-lose situation or a zero-sum game. You can’t find money for both. As the asset bubble economy that we’ve been living in for decade normalizes, or perhaps even declines, then this is really going to be a case where many municipalities and counties are going to be proverbial as time goes out and we’re going to see who is naked.

FRA: Yeah. I mean many of them have built-in assumptions of trying to get 7% to 8% yields in order to make stakeholder obligations but, as you know in financial repression, the repression of interest rates to low values has made it difficult to get yields. A big part of their holdings has been bonds. So, as yields have gone down, it has been made really difficult for the pension funds to meet their yield goals.

Smith: Right. And what has been their response? If you’re one of the fund managers, then you’re piling in to the FANG (Four High-Performing Technology Stocks) stocks, right? Piling into Apple, Facebook, Google and Netflix as the only way to get those kinds of huge returns that are required to keep the funds solvent. We know what happens. These FANG stocks are a tech-bubble that we’ve seen before in 2008. These pension funds are exposing themselves tremendous risks that are way above that of buying a 30-year treasuries or AAA rated corporate bonds, which is as you say, the normal haven for their safe positive return. They’re exposed to a lot more risk so they could end up suffering tremendous draw downs if bond yields continue to rise as we know the value of the existing portfolio on bonds declines accordingly. If the FANG stocks rollover and decline, then that’s going to hit a lot of these pension funds have counted no technology companies to make up for the low yields that you have described.

FRA: Yeah. There are already warnings on that in terms of what could happen otherwise or what could be their response. For example, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), which is actually Canada’s largest defined benefit pension plan with about $95B in net assets. They actually put on their website that deficits will be funded through a combination of contribution rate increases and benefit reductions. They’re already warning that either they’ll be likely much higher property taxes or a cut in benefits to the actual pensioners.

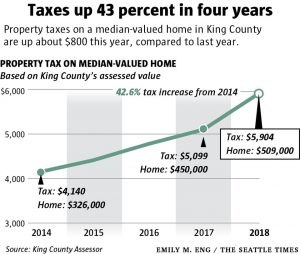

Smith: Right. And maybe we can put some numbers behind these statistics and dynamics that we have been discussing. I have a couple of charts here that I submitted to you before we started recording and the first one shows that the taxpayer contributions into government pensions and that means public sector pensions has more or less doubled in a decade from $60B annually to over $121B and that is skyrocketing. The rate of increase is far above the rate of growth of the economy. In consequence to raise these sums, then municipalities, states and cities are raising property taxes and I have a chart here of King County which is in the Seattle Municipal area.

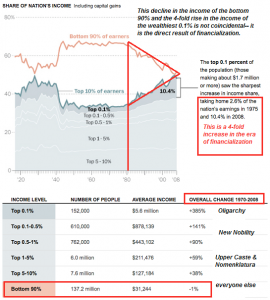

The property taxes there are up 43% in four years. Anecdotally, I just heard someone report their taxes in the Seattle area went up 26% in one year. That may have been local taxes on top of the other property taxes but 43% in four years, that’s more than 10% annual gain there. Most people’s wages have gone nowhere and I have a chart here that is dated a few years but nothing really has changed and it shows that the bottom of 90% when adjusted for inflation, the bottom 137 million households in the U.S. have lost income when adjusted for inflation.

So, the vast majority of households that are property owners are not making more net income here. They’re having to cut their other spending in order to pay skyrocketing property taxes.

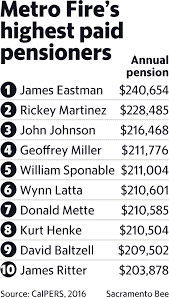

FRA: Yeah. Exactly. You also have some other charts in here as well on how, on the other side of the fence, the government pensioners have been paying themselves very lavish pensions – awarding themselves which actually only makes the whole problem worse.

Smith: Right. This was a chart from a Sacramento article regarding the Sacramento area’s fire department’s highest paid pensioners and a number of these people are earning over $200 000 a year in pensions. A $200 000 income will put you in the top 5% of American households.

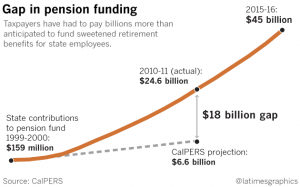

In other words, this is an extraordinarily high income and the number of pensioners in the state of California that earn over $100 000 in pensions annually runs into thousands of people. There is a sense here of great injustice. In other words, the majority of people who are paying property taxes have not seen their income soar by these extraordinary increases that these property taxes are going up by nor do they have pensions in a 6-figure range. So, it feels like exploitation to those of us who aren’t looking for $100 000 – $200 000 in guaranteed pensions. What this is doing is creating huge gaps in pension funding. I have a chart that shows an $18B gap in Calpers which is the largest of pension fund in the state of California.

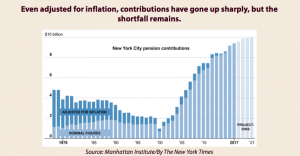

We also see here that we have a chart of New York City pension contributions which soared from about $1B annually around the year 2000 and now it is pushing $10B.

So you’re talking about a tremendous increase and the rate of increase continues. In other words, this isn’t just a one-time bump up and then the pension contributions stabilized. They continue to rise at these rates that are four or five times the growth rate of the economy as a whole and also of wages. Before the program, you mentioned that if we extrapolated these trends, where would we end up?

FRA: Yeah. I mean in your recent writings, you mentioned that the migration to lower tax jurisdictions. Like when somebody is living in Illinois, they may move to Florida. Can you elaborate on that?

Smith: Right. Right. Just to kind of set a context here. The context of what we’re describing is that cities, counties and states are under legal obligations to fund these pensions at the rates that were promised to the pensioners and the only way out of those legal obligations is bankruptcy and many states have unclear laws regarding municipal bankruptcies. In other words, cities and counties in many states do not have a clear pathway to declare bankruptcy and the only way they can raise money to fund the pension plan is to cut public services. You’re hit with the double whammy. In other words, your property taxes and junk fees are rising rapidly. Meanwhile, your library’s hours are being cut, your police departments are being cut and the roads are filled with potholes that can’t be filled unless you pass a special bond. These places that are being crunched by these pension costs – the public is seeing a deterioration in their lifestyle. The local infrastructure is crumbling and there is no money to fund it because all the money has to go to the pensions. I call the people that are stuck in these areas tax donkeys because they’re loaded up with ever higher taxes and it is difficult for them to escape in many cases because of many reasons: kids are in school, family obligations, can’t quit their jobs, etc. So they’re really stuck but there are a very large number of people who tend to be high-income and are mobile. They can leave. They either are childless or their kids have already left home. They work largely in the digital realm so they can work from anywhere. These people are going to migrate and despite the claims of the status quo of politicians in these high-tech states like California, Illinois and New York that people don’t leave. They don’t leave if the services they’re getting keep increasing in quality and quantity every year. In other words, the past is not a good guide to the future because we’ve had an asset bubble based economy for the last decade. So, municipalities have been scoring huge gains in tax revenues which has allowed them to maintain services at a very high level and fund the pensions. Once there is a recession, that goes away then the public services are going to be slashed. So, people like New York City, San Francisco and Seattle but at some point, as homelessness overtakes their neighborhood, homeless encampments show up in their block, crime starts going up, property crime and theft starts going up, and all of that stuff. Good restaurants close because the taxes are too high for them to survive. All these reasons to stay in these high-tech areas vanish. Literally over night. We’re starting to see anecdotally articles from people saying why they’re leaving their cities, for example, Seattle. We’re seeing more and more of these so migration is difficult to track. We know that there is a leakage of population from California and other cities but what is not being captured is the nature of the people who are leaving and I think that if we could dig down those statistics, we’d find that it is the most productive in terms of paying high taxes. It is those people who are leaving because they are the ones caught in the vice. The people who are staying or who are left behind are the less productive or the people who make less money, pay less taxes and absorb more of the government’s services. We can discern a very destructive feedback loops starting now. This feedback loop will only get stronger as we finally get a recession in which the high tax payers are leaving for low tax claims and leaving the people who are depending more and more on the government’s services which are going to be slashed.

FRA: Right. It seems to be an emerging negative feedback loop as you’ve mentioned that is actually non-linear as these more productive citizens leave, then the ones that are left behind are burdened even more to make up for the loss. So it just gets worse in a non-linear way.

Smith: Right. I think that is an excellent observation, Richard. When we think about small-scale entrepreneurs that make cities livable and this includes restaurants, cafes, small theatres and services for the children and elderly and all of these private sector niceties are going to be under tremendous pressure as their customers flee. So they start closing or those people that try to start a new café or restaurant quickly find that they don’t or won’t make enough money to survive as their tax rates go up. I personally am in communication with a lot of people through emails throughout the U.S. where they’re small businesses and they’re noses are just above the waterline. In other words, they’re staying afloat but just barely. There is a huge number of businesses like this that create that non-linear effect that you’re saying. In other words, if property taxes go up another 10% and a recession causes a 5% decline in consumer spending in a city or a county, you’re not going to see a 5% decline in small businesses. You’re going to see a 30-40% decline. That is a huge impact because there are so many people that are right on the borderline. Of course, we can also throw in other factors in which we can be fans of and we can support minimum wage laws and these kinds of things but they’re accumulative. For the small business owner, it is like the property tax, any other junk fees and then the minimum wage increase, and then the higher health care. Each one seems to be something we believe could be absorbed but when you add up 10%, 10% and 10%, then suddenly you’ve got increases of over 40-50% in their fixed expenses and they can’t survive. I think you’re absolutely right that there is going to be an enormous non-linear effects as these feedback loops eke into the class that pays most of the property taxes.

FRA: And the idea that the pension benefits could be cut. What do you think of that? That alone could cause a lot of social unrest, right? – in terms of people not accepting that or not willing to accept those cuts.

Smith: Right. Well, we’ve seen some examples like the city of Detroit where there was a successful municipal bankruptcy and pensions were cut, what was actually sustainable with the existing pension fund? Of course, that created a lot of unhappiness in the pensioners who felt that they have been promised “X’ and were given half of X. On the other side of the coin, in regions like California, Illinois and New York that are dominated by public unions then the war that is heating up would be first from the public tensions and the public employee’s unions versus the tax payers and in the current arrangement, the taxpayers have very little representation in the local government. They don’t really have a voice. The unions have the political influence so they’re going to fight tooth and nail to keep the pension structure as it is. I think it will require a political crisis, either a tax revolt of some kind or the complete disappearance of all cash where the cities and counties simply no longer have any money. Their accounts have been drained and have zero money to pay people. Until that point comes, then I doubt that the status quo would change. I have a chart here based on Peter Turchin’s work about the disintegrative forces and he identifies integrative eras where people find reasons to work together and disintegrative areas where they find reasons to disagree. He plots this on a political stress index. This is what he calls it. So, what we’re talking about here in the public pension and private sector versus the tax donkeys, we can see the three of the key dynamics that Turchin identified at his work: One of is the stagnating real wages. As I said, for 90% of the workforce that is getting nailed with higher property taxes, wages have not gone up in years and maybe decades. Overproduction of parasitic elites and I think that whether you want to call the parasitic elites public or private, I would lump them all together. People pulling down enormous salaries at the expense of other people – that I think, no matter how you want to describe it, I would call that an overproduction of parasitic elites and the deterioration of state finances. We see that counties and cities have and are struggling now in the second longest economic expansion in history. A tremendous expansion in stock markets and housing values and this is the best of all possible times. If we’re seeing cities and counties struggle with budgets now, then you can imagine what happens when we finally get a real recession. Clearly, we’re seeing point 3 to deterioration in state finances. This dynamic that we’re discussing is definitely increasing the political stress index and it is definitely going to create severe structural, social unrest and social discord.

FRA: Yeah. Exactly. This is very interesting on Turchin’s disintegrative forces. There’s also that idea that as property taxes go higher, we begin to wonder whether you own the property and the concept of property rights comes into question. Is it the government owning the property and you’re just renting the property from the government when property taxes get so high? Your thoughts on that?

Smith: Yeah. I think that’s a great topic, Richard! Before we started recording, you mentioned the model that goes back even to the Roman era when Rome suffered these disintegrative forces that Turchin describes in which people simply abandon their properties. They walk away from it because the taxes are higher than they can afford. The property has lost its value because of this tremendous increase in the tax burden. In my view, places like San Francisco, Seattle and New York (Brooklyn) and a lot of other places, people have tolerated these rapidly rising property taxes because their homes have gone up so much in value. In other words, you’re talking about Seattle – a $500k house a few years ago is now $800k and we see these numbers. So, when you feel like you’ve made $300k in five years or less then you feel like you can afford another five thousand dollars a year in property taxes. But if that $800k house drops to $400k in the next recession, then all of those people are going to suddenly start feeling that it is not so easy anymore to make those taxes. Even more recently than the Roman era, there have been times where cities have gone into decay and this feedback loop that we’ve described and Detroit being a famous example, the value of houses fell to zero. Well, that is an extreme or caused by an extreme depopulation and so on but we have to remember that we’re not talking just about the total value of the home, we’re talking about the home owner’s equity. So, if somebody buys a house for a half million dollar and it drops in value into $400k and their entire equity is forty thousand, they’re now under water by twenty grand. They can walk away and they’ve lost nothing. So, it depends on the debt burden that each of these home owners has taken on. That’s how we could see that even these high value cities start having people jingle mail their mortgage because the property taxes are pushed to fifteen and twenty thousand a year. That’s just a standard in Northern California and many other high value places. As you mentioned before we started recording, there was a news report that one of the branches of the federal reserve suggested a one percent wealth tax on all homes in Illinois to resolve their pension crisis.

FRA: Yes. Exactly. Already I know someone in Illinois paying about 3.3% in property taxes. So something about fifteen thousand dollars per year, over a thousand dollars a month on a house that is approximately $450k in value. To add another one percent on that is a suggestion by the Chicago Federal Reserve to add a proposed one percent on property annually for the next thirty years to cover the pension crisis problem in Illinois. That was just recently proposed by the Chicago Federal Reserve.

Smith: Right. So that one percent – the additional $2500 a year – you can imagine as in a recession, there’s even more as we say in tax revenues start drawing up. The public starts rebelling against the cuts in public services then there’ll be another one percent suggested, then another one percent. This is a dynamic that you’ve mentioned earlier program. We can see the feedback loop here that as tax revenues decline in a recession then they have to raise taxes on those people that are remaining who can’t afford to pay those taxes. Another little dynamic here is that rents in places like Seattle are skyrocketing as well and from the property owner’s point of view, if their property taxes are going up by 10-15%, 20-25% a year, then they feel that there is no option but to raise the rents that they’re charging on their properties. It doesn’t just hit property owners. It eventually bleeds over and hits everybody in a municipality: renters and owners alike.

FRA: It’s interesting when you mentioned how the property values in Detroit went towards zero, this is also been observed by Martin Armstrong who sees Illinois following the exact pattern as the fall of the city of Rome during the Roman Empire era. What he mentions is that more and more people just walked away from their property. There was no bid. Illinois is the number one state that now has a net loss of citizens; people that are fleeing the state. Martin Armstrong writes that there absolutely no hope whatsoever in fixing this problem of a pension crisis in Illinois and every solution like the one from the Chicago Federal Reserve we just discussed will fail in the end. Martin mentions that the state also has colas? (30:24) which insanely increase state employee pensions by an automatic 3% annually regardless of the inflation rate. That’s how crazy things have become. Martin also writes that because Illinois does not have its own currency, it is then bound by the national international value of the dollar. Like Greece, if the dollar rises, Illinois is thrown into deflation. Its institutions are broken and will only be remembered by history. When you plot the actual population of Rome when it emerged, it is very interesting and the stock reality that applies to Illinois is that people could no longer afford to live there. They were forced to just walk away from their homes and the value of real estate went to zero. That’s what Martin writes from the analogy of what happened in history with the city of Rome. One thing to think about in that model is that ultimately, every government or state function, whether it be a city, county, state or federal, the government depends on the private sector to generate the jobs and the income that can be taxed to support the state and its employees. As a general rule, the government in the U.S. is surrounded by 20% of the workforce. It depends on the other 80% of the workforce to generate the taxes to pay the 20% state employees. If you strangle your private sector to where it is impossible to make money, it is almost impossible to start a business that is actually profitable. What happens is that you end depending more on a few large employers. The way that Seattle used to depend on Boeing and now it depends on Microsoft and Amazon. What happens is that these large corporations are also mobile. They are the epitome of mobile capital. They don’t need to stay in these high tax areas. They can leave. They can keep a sort of a façade corporate presence but they can move the 90% of their workforce elsewhere in the U.S. or in the world. Once you become dependent on these very large employers and they move, then your city is absolutely gutted. You go down the Detroit path. Detroit became far too dependent on one industry and a handful of corporations and I see this as extremely likely that Seattle and the San Francisco Bay Area are dependent on these leaders in the tech industry. Once they go away or move elsewhere, then the tax base is going to be cut tremendously because those are the companies that are creating the high income jobs that allow people to buy these over priced homes.

FRA: Ultimately, you see sort of a combination of that with brain drain and wealth drain.

Smith: Right. Exactly. The demographic, we didn’t really talk about this much, but as we know, millennials as a generation are already burdened with tremendous student loan debt and compared to previous generations, their earnings in their 20s and 30s is considerably lower than what was achieved by Generation X and the Baby Boomers. That question comes down to whether the millennials want to marry and have children, unless they’re both brain surgeons or CFOs of a company about to go public or somebody earning extraordinary amounts of money like a quarter million dollars each, that dream is not doable anymore in a lot of places. In other words, they can’t marry and have children, have a decent life and buy a house. Generationally, what we’re going to end up with is that we’re hallowing out these very high cost houses and we’re leaving the baby boomers and people that bought their homes long ago with a lot of equity but we’re putting a lot of incentive for younger families and households to leave because that’s the only way they can afford to buy a house and have a family.

FRA: Wow. That is great insight today from Charles on emerging pension crisis and the growing tension between the public sector and the private sector. Charles, how can our listeners learn more about your work?

Smith: Yeah. Please visit me at oftwominds.com and thank you very much, Richard! Always a pleasure

FRA: Great! Excellent. We’ll end it there and do another one next month.

By Karl De La Cruz

karl.delacruz@ryerson.ca

05/20/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On The Intensifying Pension Crisis

05/20/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On The Intensifying Pension Crisis