FRA: Hi. Welcome to FRA’s RoundTable Insight .. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith. He is an author and leading global finance blogger and America’s philosopher – we call him. He’s the author of nine books on our Economy and Society including A Radically Beneficial World; Automation, Technology and Creating Jobs for All, Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change and the Nearly Free University in the Emerging Economy. His blog oftwominds.com has logged over 55 million page views and number 7 on CNBC’s top alternative finance sites. Welcome, Charles!

Smith: Thank you, Richard! Always a pleasure.

FRA: I thought today that we’d talk about trade potential for developing trade wars. Where this could ultimately lead and what’s behind it. How have we gotten to this point? We see a lot of, not just in the U.S., but in international trade war issues. This week – Brazil accusing the European Union (EU) of instigating trade wars and threatens World Trade Organization complaint. So, it’s all over the globe now. You recently had a discussion with our co-founder, Gordon T. Long, and I’m just wondering if you can relate that in terms of how financial repression has caused the trade wars.

Smith: Right! It’s a great topic, Richard, and I’m glad you brought up the issue with Brazil and the EU – showing that this is not just the issue between the U.S. and China which gets a lot of publicity but it is a global phenomenon. But the roots are global as well and at least one of the roots is financial repression which is the major central bank’s policies over the last nine years of recovery to drop interest rates to zero to buy risk assets, to push investors into risk assets and generate a lot of liquidity and credit. One of the results of that is corporations have had an easy time borrowing a lot of money and, of course, some of that have been spent on buying back their own shares and so on. There’s also been a great expansion of capacity, especially in emerging economies like China where the government is explicitly trying to create jobs. There’s been a huge amount of money poured in – generating more capacity. In other words, there are more factories, more production and more mines opening. So, the world is awash in most things. There is too much of everything because of this overcapacity. What that has led to in the private sector is the loss of pricing power. In other words, when there is an over-supply or over-capacity, then you can’t really charge enough to make a good profit. Then, the corporations with global exposure, have to start cutting costs. We’ve seen this lead into sort of an endless cycle where they first offshore production, then they offshore back office, then they slash and burn their payroll and then they move from salary to employees to contract labor. There are all these ways of cutting but eventually, you get through the fat to the meat. Then pretty soon you’re cutting the bone, right? Then you end up with zombie corporations which are still producing and are only surviving because they keep borrowing. In China, that’s the whole model of things. This thing so called SOEs (State Owned Enterprises) which they lose money. The state understands they lose money and they just keep borrowing money so they can keep their payroll. Outside of that sort of government subsidy, it creates a world in which nobody can have enough money to justify their evaluations. So, the national governments start turning to trade wars as a way of getting back pricing power and limiting the over capacity and over supply that’s crushing their domestic economies.

FRA: Do you think that the trade wars could be implemented by tariffs or by global competitive currency devaluations?

Smith: That’s a great question, Richard. Because part of what makes every discussion of trade so complicated is because different currencies are the sort of foundation of trade. If a currency is greatly devalued, then those products are cheaper for other buyers and other currencies. If a currency gains in relative value, then that nation’s export becomes expensive and their exports suffer. They talk about competitive devaluation, right? And that’s the policy in which everybody tries to weaken their currency but it’s a zero sum game. We can’t all weaken our currency, right? It’s like if one currency loses its value, it’s against a basket of other currencies. There is some question as to whether that’s really going to work. In other words, if you’re the only country that’s devaluing your currency and everybody else is stable, then you can get away with that and gain an advantage. But if everyone else is starting to play the game, then where would that lead? It’s not really a solution.

FRA: Let’s dwell a little bit more in detail about the U.S. and the U.S. trade deficit. You’ve graciously provided a number of slides. If you can go through those and provide insight on each?

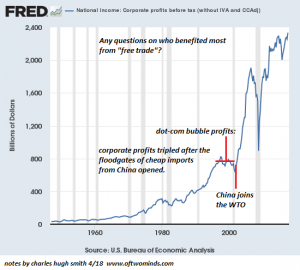

Smith: Yeah! Another thing that I find fascinating in trade is that it ties in the global trade economy. We talked about financial repression in central bank policies and how that influences it and how currencies influence trade. In terms of tariffs, I think it is important to mention that many countries such as Japan protect their domestic industries without using tariffs. They just simply use bureaucratic mazes and motes. For example, if you’re going to export something to Japan, you have go through a bunch of different hoops with various ministries and the ministries, of course, are well trained to find some reason to put your application aside for six months and for another six months because have more research we need to do. There is more than one way to protect domestic industries and bureaucratic mazes are actually more effective than tariffs and I think we may get into the political side of this later in the program. But, you know, Trump has announced a bunch of tariffs and then he quickly announces a bunch of exemptions. A bureaucratic maze is actually way more effective way to control or protect your domestic industries. To go through my charts, the first chart is of U.S. based corporate profits.

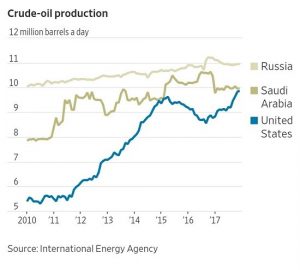

It is kind of interesting that those profits around 2000 which had shot up a lot as a result of the dotcom boom of the late 90s. They were about $700 billion a year and then China enters the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 2001. Very quickly, the U.S corporate profits basically tripled. That tells you that I don’t think this is a coincidence. That’s a stretch. Clearly, who’s benefitted from the expansion of trade in emerging productive markets like China are the U.S corporations. People that have done research and say,” Oh well, the cost of goods at Wal-Mart are cheap because of the production overseas.” They kind of guesstimated that the American consumers might have saved $200 billion or something like that in the last set number of years. However, if you look at the corporate profits going from $700 billion to $2.4 trillion, the corporations have pocketed trillions. Consumers pocketed nickels. Another chart I have here is the U.S. oil production and has gone up quite a bit as everyone knows because of fracking and other technology since.

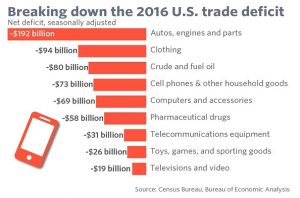

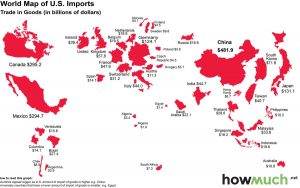

This has really relieved the pressure on total U.S. trade deficit and much of which was energy. When the U.S. was importing six to eight million barrels of oil a day, that’s hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of energy, right? Now that U.S. production has increased, it continues to import energy products and its also exporting some of its oil as well. We know that Canada and Mexico – North American Free Trade Agreement – as a whole is an energy exporter. The U.S., bottom line, has been impacted positively by its oil increase. I have a couple of charts here about breaking down the U.S. trade deficit and it is interesting because we tend to think of it as a national thing, right? What is the trade deficit with China or Germany? This tells us that almost half the goods trade deficit is related to autos and vehicles. That’s an interesting kind of fact. Imports and exports are a really broad part of the economy. In other words, it is not just soy beans and steel or aluminum. It’s a lot of different products from different parts of the world. You can see that the U.S. runs trade deficits with most of the world. Another chart I have here is the trade deficit. It is not mine. It is from somebody else.

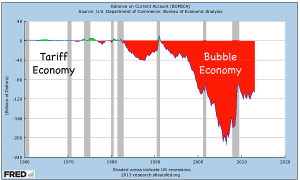

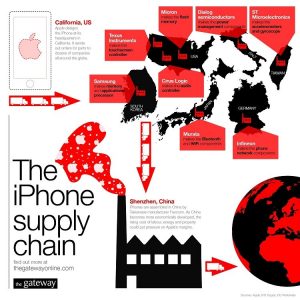

The trade deficit used to be extremely modest back in the early post 4 years. Once we got a bubble economy, where the central bank was pouring in tremendous amounts of liquidity into the banking sector and in the economy. Then we get a bubble economy. That’s when our trade deficits sky rocketed. Of course, that is a bit simplistic because oil was a big part of our imports and the strength of the dollar made it convenient to buy other people’s products. When your currency increases in relative value, then it becomes even cheaper for you to buy other nation’s output. There’s a lot going on to add to that huge increase in the national trade deficit there. So the last chart is the IPhone supply chain.

The trade is not calculated with any kind of accuracy. It is very difficult now because of the global supply chain to make sense of what trade really is. This is a good example because if an IPhone is shipped from China and lands at the dock in Longbeach, it is credited as a $500 import from China. But if we look at the components, they’re made in Japan, South Korea, Europe, America, and other nations that as much as $480 of that $500 ‘import’ from China is actually imported from elsewhere. As little as $10 or $20 may actually stay in the Chinese economy. If we calculated trade in that way, some people actually claim that the trade deficit with China basically disappears. So much of what China does is assembling components from elsewhere. That huge trade deficit with China is illusory to some degree.

FRA: It is somewhat misleading in terms of how we measure trade and that’s leading to misunderstanding as well.

Smith: Yes. That is right. Much like GDP. It includes a lot of stuff that doesn’t mean the economy is becoming more productive.

FRA: What about what’s happening in terms of the U.S. Trump administration. Do you think their strategy is to use these trade tariffs and potential trade wars as a bargaining chip for trade treaty organization in order to get the U.S. a better deal?

Smith: Yeah. I think we see some evidence to support that, Richard. That was one of Trump’s campaign kind of promises – to cut a better deal. It is interesting that when he first announced his trade war sort of policy, then companies like BMW suddenly announced they were expanding their assembly of vehicles in the U.S. It’s an interesting dynamic because if you get a political threat, then corporations don’t really have the luxury of waiting around to see how that policy is implemented. They see the writing on the wall, they see the political narrative shift and trajectory. It makes sense for them to go ahead and increase their production and assembly in the U.S. In other words, be proactive. Don’t wait around for the trade war to heat up. Just go ahead and move your product line and some assembly to the U.S. ahead of it. Ahead of the curve so to speak. We’re starting to see some of that.

FRA: Yeah. Speaking of the political angle, there was a recent discussion of placing 25% tariff on U.S. soy beans. Could this be a political ploy by China in order to aggravate the backing of Trump supporters in the U.S. Midwest where a lot of the soy beans are grown?

Smith: Yeah! It’s a fascinating supposition. I’m glad you brought that up because any kind of announcement regarding trade will have a domestic impact on the companies producing those goods. It’s undoubtedly that the Chinese leadership are trying to undermine Trump’s political support with that. If you’ve ever driven through Iowa, for example, much of the state is soy bean fields, wheat fields and corn fields. The U.S. certainly a bread basket of grain and soy bean producer of global proportions. There was some analysis that came out and said that that sounds nice – the Chinese trying to say they’re going to raise the price of U.S. soy beans but the world does not have an over supply of soy beans. So they can buy some from Brazil which is another major producer but their demand is so large that they’re going to end up buying U.S. soy beans anyway.

FRA: Yeah. There are 400 million pigs in China that need to be fed. So, without the soy beans, they’re going to run into a lot of problems. There’s only about 14 million tonnes of domestic production in China from my understanding.

Smith: Yeah, exactly. This is where it is fascinating to drill down because people are saying,” What about rare Earth metals?” This is because China has a monopoly on some of those metals and you can get into some electronic components and chemicals that the Japanese have almost a lock on for relatively modest parts of key industries. It turns out there’s only couple of factories in the world that make these things. That’s why we have to be careful about the sledgehammer to drive attack. Politically, it is also interesting to ask if it is really true that the U.S. has just been a dumping ground for the last 30 years. In other words, everybody else can over produce and just dump over their production into the U.S. market. Maybe it has been unfair. Nobody wants to talk about that but I do wonder if that’s actually a valid perception. As I mentioned earlier about the BMW thing and a lot of the Chinese machinations, people don’t want to lose the U.S. market. It is too big and important. There is no substitute. In a way, Trump has little more leverage than the exporters as far as I can see.

FRA: Do you think that the U.S. and China will follow through on these plans for tariffs? Do you think that they’ll be pushed back in the market in other countries and economic forces in general?

Smith: It’s a great topic, Richard. Before we started recording, you sent me an interesting article from the economist Barry Eichengreen – whom I understand you’re going to interview in the near future – he was talking about the fact that China and countries like China with higher export to GDP ratios than the U.S. In other words, these are export dependent mercantilist economies. They don’t really want to encourage a trade war because they’re going to be a much a bigger loser than importing countries.

FRA: They’re sort of more for free trade than the U.S., ironically.

Smith: Right! Exactly! To me, it is interesting to look at the model that’s often held up as being remarkably successful since the end of WWII which is the mercantilist model that Japan followed which was to protect domestic industries at all costs and then use government money and power to boost your export sector. Do everything you can to make it easier for corporations to expand their production for selling overseas and that enriches your nation. South Korea followed that model, Asian Tigers and China pursued that model with great success. Now, looking back at what has happened to Japan, after that whole export burst ended in a financial bubble, they’ve been stagnant. Part of why they’ve been stagnant for twenty something years is that when you protect your domestic industry, you protect a bunch of inefficient and unproductive industries. Those companies don’t make enough money to become efficient. They become sort of like a zombie sector. There is some employment but they struggle. Since there is no competition from overseas, to say that that model is successful, it is only successful in the boost phase. But once you get to the point where you’ve protected a bunch of inefficient and unproductive domestic sectors and you run into competition in the global stage with your exports sector, then you get stagnation. Japan’s export sector is still large but look at the profitability problems they’re having. It turns out that big electronic industries like Toshiba and Panasonic, they’re riddled with financial scandals because they’ve been overstating their profits by trillions of yen for years. They’re really not profitable anymore. So much for the mercantilist model. It only works for a while. It is not a permanent successful model. There are blow backs and consequences. To put it another way, trees don’t grow to the sky.

FRA: Rather than imposing these tariffs, could the U.S administration focus action on intellectual property rights dispute between the U.S. and China on IP (Intellectual Property)? Could that happen?

Smith: It is important because a lot of what the U.S. exports is software, films, entertainment and all of those things are easily pirated. We all know stories that you could get the DVD of the movie in Hong Kong’s streets before it is even released in theatres. We have a lot of friends in China and they report to us. In general, for the Chinese people, software is like air. Everybody should be free to everybody. It is not considered theft as we would see or it as Microsoft and other companies would see it. Trying to control the theft of intellectual property is very difficult. It is worth doing. You have to make an effort if your export sector is heavily dependent on intellectual property like the U.S. is but I just don’t know how much you can really change that dynamic. It is very difficult to stop thievery except at the official level.

FRA: Where do you see all of this going in terms of the next phase of trade war discussions? Could this cause inflation in consumer prices because now the U.S. actually have to make the dishwasher or microwave oven here rather than importing it because of the large tariffs. Do you see that potentially happening – much higher inflation?

Smith: Right. I do wonder about that. People are starting to say,” Oh well, you know, you put tariffs on steel and aluminum and that’s going to ripple through the economy.” We have to start asking. What percentage of our products are basic materials like aluminum, steel and soy beans? If you take a box of cold cereal, it turns out that the grain is something like a nickel or a dime. If we look for inflation, it could be in finished goods, if there’s tariffs on finished goods, that could really hurt like auto parts. If people start slapping 25% tariffs on finished goods, that could have a really big impact. The alternative view is if those producers decide to move their production to the U.S. and go ahead and absorb the higher labor costs and taxes here, it might be awash. In other words, the actual sticker price might not go up that much or there would be benefits in terms of supporting U.S. employment that certain number of higher prices would be offset by bringing the supply chain home, stronger employment here, more taxes being paid and so on.

FRA: Finally, what are your thoughts on how trade wars could potentially lead to physical wars? If we absorb more labor in the U.S. that would take away labor in China and the ruling party, there is concerned about that – causing social unrest. Could all of this morph into physical wars?

Smith: There’s a famous quote by a French economist, Bastiat (Frédéric Bastiat), from the 19th century and I’m just paraphrasing. I don’t have it in front of me but it something like this: If goods don’t go across borders, then soldiers will come across borders. Kind of implying that dynamic you’re mentioning. I think trade is about 10-20% of most major economies – imports and exports together. We have to try and remember the scale. We’re not talking about most countries having 50-60% of their economy based on imports and exports. Trade is a critical sector of every economy but I think that the potential for disruption politically is in those countries that are super dependent on trade. Now, that would include Germany of which about 40% of their GDP is related to trade, as I recall. And China and these mercantilists based economies. They are much more likely to suffer political blowback and domestic turmoil and escalating sort of trade war environment. That domestic political turmoil and disorder is much more likely than a shooting war because trade wars are more relatively controllable compared to an actual combat war – where there is really a high risk where things get out of control. It is more likely that there will be domestic turmoil and that’s what politicians will have to focus on – how to deal with their domestic turmoil as a result of trade being disrupted.

FRA: Wow. That’s great insight, Charles, on this potential for trade wars. How can our listeners learn more about their work?

Smith: Please visit me in oftwominds.com. I got three chapters of my most recent books and big archives and come visit me at oftwominds.com.

FRA: Excellent! Thank you very much, Charles.

Smith: Ok! Thank you, Richard. My pleasure!

By Karl De La Cruz

karl.delacruz@ryerson.ca

04/23/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On The Developing Trade Wars

04/23/2018 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On The Developing Trade Wars