FRA: Hi welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight .. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith. He’s author leading global finance blogger and philosopher, America’s philosopher we call him. He’s the author of nine books on our economy and society including “A Radically Beneficial World Automation Technology and Creating Jobs for All”, “Resistance Revolution Liberation a Model for Positive Change”, and “The Nearly Free University in the Emerging Economy”. His blog of twominds.com has logged over 55 million page views. It is number seven on CNBC top alternative finance site. Welcome Charles.

Charles Hugh Smith (CHS): Thank you Richard. Always a pleasure to join your roundtable.

FRA: Great. And with that today with the focus on the sort of tension between the private sector and the public sector with many types of revolutions, technological revolutions happening in the in the private sector you know in terms of block chain and biotech, energy environment, lots of revolutions happening much like what happened with the with the Internet.com revolution. And the question is will that growth in the private sector be able to to meet the challenges of the public sector in terms of seemingly unsustainable growth and that growth in Entitlement programs. Dr. Albert Friedberg of the Friedberg Mercantile Group recently observed that in the U.S. it’s basically 10 percent of GDP and rising for entitlement programs. So you know that’s the big question. Your initial thoughts.

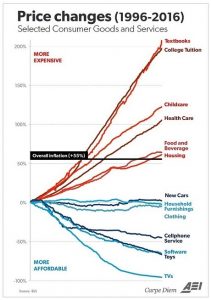

CHS: Well Richard I think that’s an excellent context for you know the points we’re going to make. And one of the first points I would start with is ultimately the public sector in this state what we call the state all all layers of government and government related entities. They all live off the private sector right. That the private sector has to generate surplus. It has to generate wages for employees and those are taxed by the public sector and that’s the source of the public sectors revenues. And so what we’re really kind of discussing is can the public sector generate enough profit and employment to support this fast ballooning public sector. And you mentioned the entitlements growing by 10 percent. And I have this chart of consumer goods and services.

The price changes what what we might call inflation. But it’s actually not. Not entirely inflation it’s it’s the cost of services being provided and how far above or below they’re rising then like people’s wages which household incomes as we all know if and stagnating for somewhere between 40 years and 10 years and depending on which sector of the economy you’re looking at. But we look at what is soaring in price and we look at like 200 percent increases and we find out it’s college tuition and we look at what’s climbing at a 100 percent or or more and it’s like health care and child care. And of course these are the sectors that are heavily controlled or are funded by by the public sector. And what we find is declining in price is cell phone service, software, TVs the kind of things that the private sector provides. So it’s pretty clear when you have competition and when you have exposure to innovation then you get it lower prices or at least you get more for your money. Or there’s there’s hope that innovation will impact the consumers, either the quality of the goods and they’re receiving or the price of the goods and services they’re receiving. So to sort of summarize everything that the public sector controls is skyrocketing in price and the quality is also now suspect right.

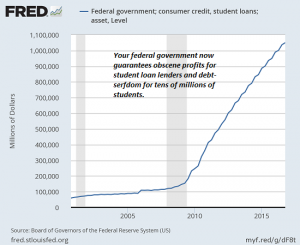

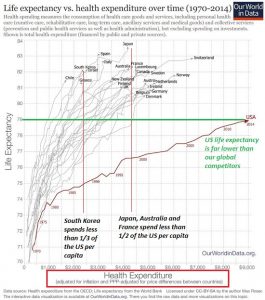

Like I’ve written a lot about higher education and I have another chart here showing that literally all of the the the higher education student loans that are being issued are actually funded by the federal government. So it’s it’s actually the federal government is funding these private sector lenders and guaranteeing them profits to fund these students getting diplomas which are declining and real world value. You know in terms of statistically what the earnings are of college graduates and so on that that’s been stagnating just along with the rest the wages. So I would propose that higher education is actually declining in its utility and value despite the cost soaring and many other people would make the same claim about health care at least in the U.S. Is that the cost keeps soaring but the actual you know measures of health of the American population are continue to decline. So this is a really striking difference. I think that’s really what we’re talking about is an enormous difference between the sectors controlled by the public sector and those controlled by the private sector.

FRA: Yeah you’ve written a lot about that in terms of several industries being sort of cartelized, you know with special interest group, lobbyists and just the interest by the government in them. Can you elaborate a bit on that?

CHS: Yeah I think that’s a great topic. If the public sector controls something like health care which in the US is dominated by the public sector programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans Administration. Then the way to maximize your profit is to lobby the public sector, lobby the government agency, to lock in your cartel pricing. And so that’s what we see is that we see these pharmaceutical companies routinely raising prices 30 40 percent or even 400 percent just on a random basis that they make no claims that they’ve invented something new. They simply raise the price on an existing medication and the public sector also imposes a lot of regulations that some of which are of course important and necessary, but many of which are simply you know churn you know they just create more work, but they’re not really creating that not really impacting the patient in any in a positive way.

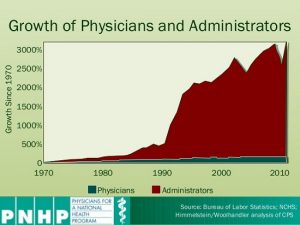

So I have a chart here of the growth of physicians and administrators in the health care system. And we see that the number of physicians has been flatlines for like 40 years where the growth of administrators from about the early 90s on has has ballooned up like 3000 percent. And so this is there’s no way that a private sector company could could bloat its management by 3000 percent and get away with it unless its revenues and profits were rising even faster.

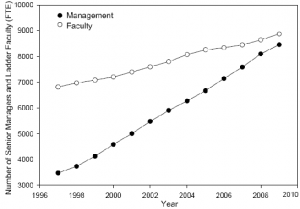

And we see the same thing and I have a chart here of the faculty and management of the of the University of California system and it shows that while the faculty has risen slightly over the last 30 years from about 7000 to about 8500 the number of administrators has risen from about 3000 to like 7500. So we have these enormous ballooning of bureaucracies and all of which are really highly paid positions. And and yet where is the output. I mean where’s the gain in quality or any output. And of course there isn’t any. None that we can measure.

FRA: And associated with this involvement by government is an increase in government debt. And if you look at just debt in general in recent years in the developed world it’s taken more and more new debt to create $1 in GDP. I mean the figures are something like $4, of between $4 to $18. I’ve seen some estimates of new debt to create $1 in GDP. Your thoughts on that.

CHS: Right. Right. And I just read a report from a blog that showed that China has the same similar, very strong diminishing returns on its vast expansion of debt. That it’s expanding debt at rates that are multiples of its GDP growth. And so it’s also the case that even in the developing world the same diminishing returns that you describe is that is the dominant reality. And of course we have to ask why is there such a low efficiency or low productivity rate to this new debt. And and it’s because there’s no there’s no pressure of innovation and competition on how the governments are spending this money. And so there’s really no adaptive pressure in terms of natural selection for them to find more efficient ways to do whatever it is they’re doing. Right. The pressure simply to raise more revenues. And if they can’t do that then to borrow more money and this is where financial repression comes in because the only way the public sector can keep adding debt and it’s at this fantastic clip is to lower interest rates to zero or near zero. And create all these perverse incentives for speculation that we’re seeing now as a result of that manipulation if you will or intervention to keep interest rates low enough so the public sector can keep borrowing and borrowing and borrowing, you know to infinity.

FRA: Any ideas on what the endgame could be here if we consider the level of debt and the level of interest rates for the two lever’s, you know with rising debt at some point even small increases in interest rates could be disastrous. I mean where does this all end.

CHS: Right. Right. I just saw a statistic which I can’t verify of course but it sounds fairly close to me. Somebody said that the point six percent rise in the U.S. Treasury yields. That’s a kind of recent rise in one part of the Treasury bond yield spectrum generated 1.7 trillion dollars in losses right then and there you know just a relatively modest increase in only one part of the total global bond market created almost 2 trillion in losses. And so yeah if we extrapolate the possibility of of interest rates going up two or three percent then you’re talking about losses that could be in you know 10 trillion and up in the bond market and then of course as yields rise historically people sell stocks with low dividend yields and high risk. And then if they take the benefit of a higher yield in bonds and so stock markets tend to go down when interest rates go up as well. So we are the end game there is can they can they keep creating debt at a fast enough rate as the returns on that debt continue diminishing. And by some measures as you know that some people feel the return is already negative, like there is by the time you include debt service and other factors than actually we’re losing ground here. So eventually that will erode the the real economy. And I think that’s that’s really what we’re talking about here is can the public and the private sector outgrow the debt that’s being piled up by the public sector.

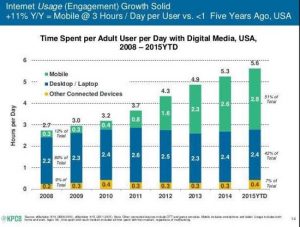

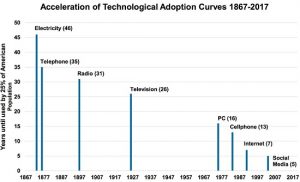

And I have a chart here. It’s kind of interesting that shows the adoption rates of technologies and it goes back into the 19th century and shows how long it took for electricity and telephony and radio and so on to be adopted by the general populace. And of course as we all know from our our own experience the adoption rates are speeding up for things like cell cell phones and the Internet itself and social media. And so we’re seeing like a faster rate of adoption and development and in the private sector and we’re seeing a glacial change in the public sector or actual resistance to any kind of innovation or change. And so I think the one of the endgames is that people the taxpayers might just simply be run out of patience with with having to pay higher taxes for lower quality public services. Right. And this could this could be a problem because as we all know public pensions are many of them are not really solvent and they’re based on unrealistic expectations of earning seven and a half percent, you know forever. And the number of people pulling the pensions drawing on the pension funds is rising fast as the boomers retire and so on and so there’s it’s not just entitlements but the entire pension system public and private is under pressure as the boomers retire and the wages of the millennials and the younger workers remain stagnant. So there’s there’s a whole other dynamic here that the public sector is going to be forced to borrow trillions more to make up these shortfalls in pension funds if it’s going to meet all those all those promises. On top of the public entitlements of you know social welfare, social security, health care, and so on. So yeah there’s there’s a number of pressures building and what’s the endgame? It’s anybody’s guess but if you destroy or or fatally wound the real economy then there’s no way that borrowing more is going to fix what’s broken.

FRA: So you think none of these revolutions in terms of like block chain in biotech and in others is strong enough for it deep enough to overcome with the general trend is in the public sector.

CHS: Well that’s an excellent question Richard because I mean my book that I wrote about higher education and that the nearly free university. The tools to dramatically reduce the cost of a college education are already enhanced. And of course this is not just remote learning but it’s also in my mind the key is not just remote learning and taking the best of what’s available and making it available to students digitally, but there’s a lot of possibilities for public private sector apprenticeships which are much lower cost than than supporting this gigantic campus with a huge bureaucracy and 42 deans of student affairs and his whole it tremendously expensive infrastructure. The way what actually is the most effective way to learn is to get out there in the real world and augment your book learning or your lecture learning or your lab work with actual experience in the field then of course this is how it works with the construction industry and many other trades. But it also works just as well in the scientific community. And I know for many of our young friends who graduated with degrees in biology or computer sciences they discover that they really don’t know what the employers really need them to know. And so that’s just one example of the kind of revolution that could occur in public funded sectors if the sector allows innovation. And so it’s like how do we break down the resistance of the status quo and the insiders who are benefiting. And I don’t know that we can but at some point when a system becomes completely unaffordable then people will flock to some new alternative and you know health care as another example people might just start going around the existing public sector and buying their own health care services at you know 10 percent of the cost of the official public sector fund. So if there’s definitely a battle royal you know over these sectors that are bloated and efficient super high cost and increasingly unaffordable. And so I’m hoping that it’s like a logjam. You know that is blocking the river of innovation and lower costs that something will break that logjam and exactly what that could be would would have to be some public sector agency or state agency that that broke away from the status quo and accepted a much lower cost model. And that’s what I hope for.

FRA: Could there also be maybe a geographic solution to this in terms of certain countries promoting innovation like Chile has has a program to encourage innovation with new immigrants you know could there be that type of solution. Maybe new countries that take on, you know more innovation that are regulatory friendly to business so that perhaps this is you know a brain drain and wealth drain from from the more stressed countries that we’re talking about.

CHS: That’s a great dynamic that you’re describing and it also works within within regions, like the EU or the United States or North America. And so I think that that’s probably the most likely vector or trajectory for real change is somebody somewhere allows or encourages the kind of innovations we’re talking about and they start reaping these tremendous rewards and and capital and talent and then are attracted to to those places. And as they drain away from the high cost places like Illinois and California and some of the developed nations as a whole then those those those places have their tax base has reduced their the profits generated by their private sector go down as talented capital flees. And so then there is a kind of Darwinian competition that the really high cost sclerotic bureaucratic unfriendly to business and innovation places become insolvent and then they’re forced to change or they or they just with her wither away. So that’s an excellent point. And I think the block chain is another example of that dynamic that whatever country fully legalizes block chain technologies and crypto currencies, like Japan appears to be doing. And it’s sort of baby steps. Even the U.S. appears to be integrating the crypto currencies into its investment sort of scheme. Those countries were prosper compared to countries that are trying to ban crypto currencies and block chain or limit them or co-opt them, you know like make a public sector version and force everybody to use it. Those kind of attempts to to stave off innovation will definitely fail and there’ll be a Darwinian selection process, whether it’s really not controllable because you know you can’t really force people to work hard and you can’t force them to put their money in places that that money is treated badly.

FRA: Could the reaction by governments be similar to what has recently happened in what is happening in Spain for example like with Catalonia. Could that be a blueprint for what is to come in terms of preventing brain drain wealth drain? You know the sort of the within the regions you see that potential.

CHS: Yeah definitely that what we’re talking about to some degree here of course is financial repression that the public sector manipulates interest rates and yields and and then and tries to subvert ban or limit innovative technologies like block chain. And then of course that what you’re describing that financial repression if that isn’t enough then they move to direct political repression. And you know one of my favorite quotes and I’m paraphrasing here was from Napoleon Bonaparte. And who is reputed to have said something along the lines of “what amazes me most is how little power can actually achieve”, In other words if you’re going to use force it’s remarkable how little force can actually accomplish. Because you’re you’re having to monitor and enforce something that’s unpopular that’s going to that’s a tremendously high cost of insurance. And so that’s a good way to go broke is trying to force people to do something they don’t really want to do. And that that doesn’t benefit them. And so I think if we had to summarize what we’re talking about it’s the public sector is default setting is to try to force everybody through financial and political repression or propaganda to do what benefits the public sector and it’s cartels and fiefdoms. But you really don’t. You can’t change anything unless you create a benefit for people that they want to adopt a new change or adopt innovation. They want it because it benefits them in some broad fashion. So and that’s really the battle we’re talking about between the public sector which tends to want to force everybody to do what benefits itself and its insiders and the public sector which realizes the only way you’re going to sell anything, whether it’s an idea or a concept or a product or service, is if it benefits the consumer and the citizen. So and of course you know anybody from the outside we would look at the public sector and go why don’t they accept a more public-private sector mentality. Why don’t they understand they have to generate additional benefits for people not by borrowing more money to pay for like a bloated inefficient corrupt system. But to foster and encourage innovation that that lowers the price of goods and services because it’s more productive. So that’s that’s really kind of the battle that’s being played out I think throughout the world.

FRA: Yeah. Well that’s great insight Charles as always. How can our listeners learn more about your work?

CHS: Please visit me. Oftwominds.com. There’s free free chapters of my book and thousands of various rants and essays.

FRA: OK great. Thank you very much. We’ll do it again next month.

CHS: OK. Thank you Richard.

Summary written by Boheira Manochehrzadeh <bmanoche@ryerson.ca>

10/27/2017 - The Roundtable Insight: Charles Hugh Smith On Will The Private Sector Be Able To Grow Fast Enough To Meet The Demands Of The Public Sector?

10/27/2017 - The Roundtable Insight: Charles Hugh Smith On Will The Private Sector Be Able To Grow Fast Enough To Meet The Demands Of The Public Sector?