FRA: Hi – Welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight. Today we have Charles Hugh Smith. He is America’s philosopher as we have called him in the past. He is the author of 9 books on our economy and society including: A Radically Beneficial World: Automation, Technology and Creating Jobs For All, Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change and The Nearly Free University and the Emerging Economy. His blog, OfTwoMinds.com has logged over 55 million page views and is number 7 on CNBC’s top alternative finance sites. Welcome Charles!

C. H. SMITH: Thank you Richard. I always wonder if I can live up to that glowing introduction.

FRA: You always do. You have great insight as always. I thought maybe today we take a look at a topic you have written a lot about and that is on stagnant wages, particularly in the developed world such as the U.S. and Canada, and what the challenges are behind that…Why it’s happening and if there are any solutions to get out of that trend.

C. H. SMITH: Right – Well it’s an excellent topic. It confuses the conventional economic commentators because as of right now we all know in the developed world, at least in North America, the unemployment is quite low – It’s less than 5 percent which is considered full employment. Normally when we have full employment then employers have to start bidding higher wages and benefits to attract the most productive workers. A rising tide raises all ships and in other words wages tend to rise across the board. When you have full employment and a rising gross domestic product, but we have rising GDP and very low unemployment, according to the statistics, and our wages remain stagnant so something has changed. So I think that is the question that we are going to try to explore.

FRA: And as your writings have indicated that there are a lot of explanations that include automation, globalization, offshoring, the high cost of housing, the climb in corporate competition, the failure of the educational complex to keep pace, a global labour arbitrage as a big factor. What do you make of those explanations?

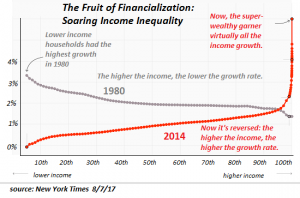

C. H. SMITH: Yeah – I think all elements and part of what we’re proposing here is that there is not just one explanation. If we could just nail it down to one cause then we might be able to change that which policy, but what you’re talking about is these very large structural forces such as globalization and the fact that the economy is changing faster than our higher education systems can change so they are falling behind what employers actually need employees to know. And so these are structural and very difficult to modify or change with just a few policy tweaks here and there. That’s not even mentioning the impact of financialization and financial repression which we all know has kicked into gear in the 21stcentury. That has also changed the distribution of the gains we’ve made from productivity. I have a chart here that the New York Times published in August indicating that virtually all of the income increases over the last few years are now going to the top half of 1%. That’s completely different than it was in the 80’s and 90’s where the distribution of increasing incomes was skewed to the lower end income and middle income sectors. That to me shows the impact of financialization because we know the top 0.5% are generally not people inventing something wonderful, they are not Steve Jobs, they are people that are simply getting nearly free money from central banks then using that cheap money to leverage it into ownership of income streams. They are not creating any income streams they are simply acquiring them with all the evil fruit of financial repression, cheap money, limited liquidity and high leverage.

FRA: For our listeners, Charles has made a collection of charts that provide good insight and we’ll have those charts in the write up of this podcast as well for everybody to look at. If you could go into what is the need for rising wages – the whole system is based on rising wages, could you go a little bit into that and why stagnant wages is a problem?

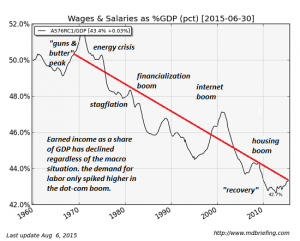

C. H. SMITH: Yeah – That is a critical point because our whole economy, the advanced post-industrial developed economies, they are all consumer economies – They depend on consumers buying goods and services on a permanent basis. So you have to have higher wages in order to support more consumer spending and more consumer borrowing because if we are going to borrow more than we need to make more net income so we can service that higher debt. So stagnant wages throw a monkey wrench into the whole permanent growth and expansion of consumption that our economies are based on. Now we can question that model and say what we really need is a growth model where we are actually getting more happiness and satisfaction with using less resources are earning less income, but that’s a discussion for another day. The economy we have is one that starts falling apart if wages stagnate or decline. I have a chart here of wages and salary as a percent of GDP and it’s quite interesting because it goes back to 1960. It’s basically a measure of how much of the economic activity or output of the economy is going to wages and salaries. What we find is is that it’s dropped quite a bit. In the 70’s, about 50% of all the GDP went to wages and salaries such as working and self-employed people, now it is hovering around 42% or 43%. That is a significant chunk because the GDP currently is about 18 trillion, so if you’re talking about 7% of that then you’re talking about a trillion dollars that used to be directed to wages and salaries and now is going to corporate profit or financier profits and basically financialization. So that’s a big change, but it’s secular, in order words it started in the 1970’s with the stagflation of the 70’s then it continued to climb in the financial boom in the 80’s and the only counter trend was in the Dot-com era, then the percentage of the GDP growth that went to wages and salaries actually increased, but when that boom ended it went back to a decline.

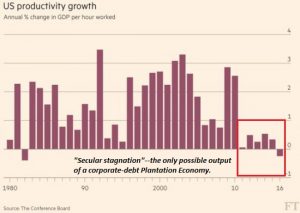

So we have to look for answers that don’t just start 5-10 years ago, we have to look back and say something has been happening for a decade or two. One possibility is productivity, that if we look at productivity growth – I have a chart here that goes back to 1980. Obviously it’s a volatile metric, it goes up and down depending on if the economy is entering a recession or not, but recently even though we’ve had strong growth in the GDP, the productivity has been very anemic and not just for a year or two but since 2010. That’s another change that’s undermining wages and salaries because all real growth comes from increases in productivity.

FRA: Now in some parts the local governments, which have growing budgets tied to increased collection of property taxes due to rises in housing prices, that could also become problematic in a similar way in the public sector if the housing prices stagnate or decline. How are property taxes going to be maintained or increase based on budgets that are factored in for growth?

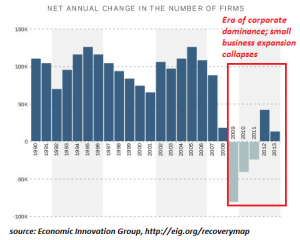

C. H. SMITH: That’s right and an excellent point – And especially for municipalities and states where the majority of the local government income is largely based on property taxes rather than sales or income taxes. And of course if wages stagnate then people have less money to spend so sales taxes stagnate, they have less income so income taxes stagnate and then they can’t afford to move up to more expensive housing if they can’t afford the property tax. I think we can see the local governments around the U.S. are feeling a dwindling, a stagnation of their revenues. Another thing is I have a chart here of the annual change in the number of new firms or in other words how many new companies are emerging and succeeding enough to hire employees and pay taxes and all the good stuff that we expect of new business growth – That has been stagnant or declining since the 2009 global financial crisis as well, compared to the previous decades of very strong growth of new small businesses. That’s another element, it’s becoming more difficult to start a new business and to succeed. That also means that there is less opportunity for wage earners because the fast growing small businesses tend to be the engines of employment because they are growing fast and need talent and are willing to outbid existing corporations for the best talent and so they are a big part of higher wages. That is also causing stagnation in wages and salaries.

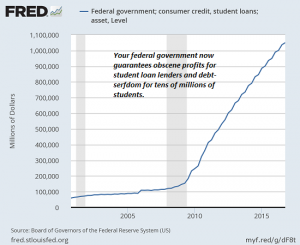

FRA: So, if we consider the big reason of financialization as the reason that wages have stagnated and that the economy is optimized for financialization, can we focus on that to explain what is financialization, how does it work, what does it mean to the average consumer and so what’s exactly happening behind financialization?

C. H. SMITH: That’s a great question. It’s a word that has various definitions. My personal definition is that it’s the commodification of everything in the economy into something that can be marketed globally. So for instance, home mortgages in North America, back in the ancient days or 20 year ago banks would originate a mortgage and hold it. It was a very slow, steady, low-risk business with a guaranteed return. Once that financial industry got financialized then the mortgages were packaged into financial instruments that can then be marketed globally as investments and then they could be sold as AAA-rated instruments to credulous investors and huge profits could be spun off of this. So that’s an example of how financialization works, is that it’s basically taking what was once a low risk industry and hyperfinancialzing it so it could be sold off and traded for immense profits. The high risk that is generated from that is then passed onto other people. The role of central banks in financialization is that the cheaper you make money, the more speculation that you enable. For example in the housing bubble of 2007-2008, that speculation was fueled on both ends of the spectrum. You had small-time players getting liar loans, which were of course enabled by central bank liquidity. And then you’ve got financiers that were selling F-rated financial instruments as AAA-rated. Nowadays, because of the credit-tightening and the regulations that were finally imposed on the banking sector, the small fry doesn’t really have the same access to liar loans and easy money, and so now it’s congregated up in the very top of the wealth power pyramid that if you’re a financier or a corporation, then you have almost unlimited access to cheap money. You can sell bonds at low rates or borrow money from a money centre bank at rates that no normal employee can possibly match. So the corporations can do thing that would not have been possible without financial repression because if they had to pay 7% or 8% to borrow the money, then it would no longer make sense to buyback so many millions of shares of their company in order to boost their wealth and capital gains. So it’s the cost of money and the availability of money to the apex of the wealth power pyramid and that’s why the chart from the New York Times shows that the vast majority of income gains over the 21thcentury are congregated over that very small part of the population that has access to unlimited liquidity at very low interest rates and then they can buy the income streams and outbid everybody else. I think that is one of the devastating impacts of financial repression, that the benefits are not evenly distributed. If you and I could go borrow a billion dollars at 1%, we could do some amazing things because all I would need to do is buy bonds that pay 3% and I would be skimming 2% for nothing. I would be earning 40 million dollars a year simply because I have access to cheap money. That is one of my favourite examples of how financialization works.

FRA: And you’ve got a great quote from one of your blog writings earlier this month saying, “Financialization funnels the economy’s rewards to those with access to opaque financial processes and information flows, cheap central bank credit and private banking leverage.” Those aspects cover what a lot of what financial repression is about such as cheap central bank credit – The whole money printing and quantitative easing aspects of central bank activities.

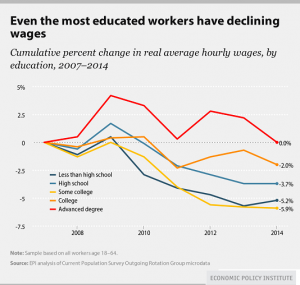

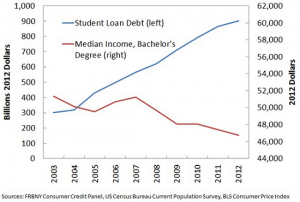

C. H. SMITH: Right – And the fact that for the 99.95% of us, we can borrow money to do something specific, modest and limited such as buying a house or getting a small business loan if we jump through a lot of hoops, but we can’t go borrow money with the size and leverage that the big players can – That’s why they’re scooping all the income gains. If we look at the chart here of declining wages for all layers of the educational accomplishment, in other words even the workers with advanced degrees, their wages are stagnating too while those with less education may actually be declining once you adjust for inflation. This is quite amazing that even the highest educated workers are no longer making gains. That shows how pervasive the damage is with financial repression.

FRA: That is an interesting chart. And if we can now ask what is the way out of this – Are there any solutions? Could a repeat of the dot-com bubble, where there was a break in the trend, be repeated through the revolutions we have going on like in blockchain, bio-tech, energy & environment, robotics. There are a whole bunch of revolutions that are happening in different industries. Could any one of those or perhaps collectively altogether duplicate a dot-com effect?

C. H. SMITH: That’s a great question and I think the more we learn about each of these scientific and technological revolutions, the more potential we see. Just as a beginning comment: there is a lot of media coverage of the replacement of human-beings such as the self-driving driving vehicles which are going to get rid of millions of drivers, that is definitely a real possibility, but we have to also make mention of something that is less sexy which is that a lot of technology tends to augment human labour. For instance, an industrial robot on a factory floor, it doesn’t just do it’s thing with no human interaction for months on end, years on end. More and more you need to change your product line very quickly and modify your production and so you actually need skilled humans to reprogram the robot. There is a lot of this kind of technology where the tool increases human productivity, but humans are definitely still the key part of the whole chain of production. So I think there is a definite possibility for higher wages which would basically mean the higher productivity that’s flowing from technological advances would go to those doing the work as opposed to those who own the income streams. But I have to say we are going to have to find some way to limit the predation of financialization in order to press those gains down the wealth power pyramid to those who are actually doing the work and creating the advances. That’s going to require certainly a political change that puts limits on financialization so there is more of the nation’s income left to be shared with the workers.

FRA: Could all of these trends have deflationary effect on the economy in terms of the need to sell assets for generating enough income to service debt and to pay ordinary everyday expenses? Do you see that potential in terms of deflationary effects on the economy in general?

C. H. SMITH: That’s a great question because it calls to my mind Japan, which as we know has been sort of in a deflationary cycle for roughly 25 years. When we look at Japan there are many aspects we can comment on and it’s stagnating too in terms of it’s wage structure and it’s growth. But one thing we might posit is that Japan’s export industry, it’s most productive sectors like automotive and various technology sectors, their productivity is increasing enough that Japan’s national economy has been able to stumble forward in a very low growth and stagnate way, but the very high productivity of the industrious sectors of Japan how allowed that to be modified. In other words, without those high productivity industries, then Japan would be in a real perhaps deathbell of deflationary dynamics. My point here is that if you have these very productive revolutionary technologies, they may be a small sector of the overall economy in terms of a percentage of economic activity, but in terms of the gross and productivity that they create, they have an outsized impact. So we might see something like that and we may be already be seeing something like that in the U.S. where the sectors that are growing fast and creating a lot of value are keeping the U.S. economy from entering a deflationary cycle. And because we know one cause of deflation is technology lowers costs and so things get faster, better, cheaper, or at least that’s the idea. That’s not a very complete answer to your question, which I think is a good one, but my point being is that technological revolutions can lower the cost of goods and services which is deflationary, but their productivity gains can increase the GDP which tends to counter that deflationary impact – In other words the whole economy can be growing even as prices decline.

FRA: That’s interesting and great insight – How can our listeners learn more about your work, Charles?

C. H. SMITH: Please visit me at OfTwoMinds.com

FRA: Great – We’ll have you on again. Looking forward to the next discussion.

C. H. SMITH: Thank you so much Richard – It’s been my pleasure.

Transcript by: Daniel Valentin <daniel.valentin@ryerson.ca>

LINK HERE to the podcast in MP3 Format

10/01/2017 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On Why Wages Are Stagnant In The Developed World

10/01/2017 - The Roundtable Insight – Charles Hugh Smith On Why Wages Are Stagnant In The Developed World