FRA: Hi, welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight .. Today we have a very special guest. He’s Morten Arisson. He’s a Canadian economist, whose work in interest focuses on portfolio management, investing history, probability and mathematics. He has worked in strategy consulting, private equity and credit portfolio management. He’s written a book called Investing in the Age of Democracy. In that book he explains how democracy, beginning with the American and French revolutions, shaped the way we currently invest in the 21st century. He proposes an alternative approach to investing based on 4 key features that are unique to the Austrian School of economics: class probability, the role of entrepreneurship and institutions, and the notion of inter-temporal exchange. Followed by ultimate consequences, these define a unique investing method. So what he has done is structured the book in 10 lessons where history, math, law and economics mix to provide the reader with a rich perspective that stretches from ancient Rome’s first investment vehicles to high frequency trading in the 21st century. So we’re going to explore that today with Morten. Welcome Morten.

MORTEN ARISSON: Hi, thanks for having me Richard – a pleasure.

FRA: Great – so I just want to mention that you were kind enough to put some notes together that we will put into an overall transcript once this podcast is published so we’ll have a transcript plus a podcast that people can either read or listen to the podcast or both. Just wondering a little bit about your background on economics – how you came to look at the world through an Austrian School of economics perspective.

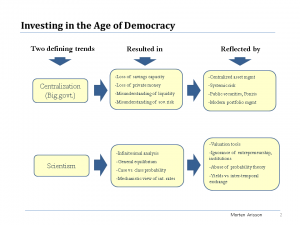

MORTEN ARISSON: Okay – I was educated in Economics. I have a bachelor’s degree in Economics, but it was only recently, a few years ago, that I became very interested in Austrian economics and I went to the conference at the Mises Institute, in Auburn in 2011 – And I did further research and I really liked the work of a gentleman from Spain, Huerta de Soto. He has written extensively about the issues of dynamics, coordination in markets, probability and so forth. And you know, being familiar with the Austrian school, I often heard that it is not clear whether one can say that there is a unique investing method that would define Austrian Economics, in an applied way. This book was a challenge for me. I was going through some pillars, some defining characteristics of the school of thought, and I think that if you follow them to the last consequence you can actually organize a very rigorous structure, a consistent investment method that will be unique. The book obviously asks why, if that is the case, market forces would have not led us there. I argue that we would have been there had it not been for interventions which are of political nature and have a lot to do with the political developments that we have seen since the French and American revolutions. So, broadly speaking, there were two trends: one was centralization – also sometimes understood as big governments – it has been increasingly growing since then, and at the same time Scientism, which is a term that was brought forward by Hayek, if I’m not mistaken, Friedrich Hayek. It mainly describes the abuse of the scientific method; in this case, to humanities. These two have created a lot of situations, gave place to a lot of interventions by governments that in a way ended up taking us apart from this approach to investing.

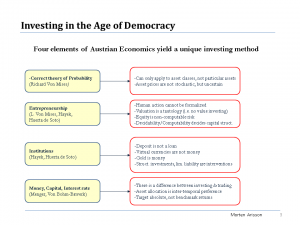

FRA: And so what you’ve done is you’ve identified 4 elements from the Austrian School of economics that yield a unique investment method if you want to go into some detail on that.

MORTEN ARISSON: Right. Probably, I should expand a little bit more first on what each, centralization and Scientism, do to the way we look at investing today and how the pillars define that method. So, in terms of centralization, we have seen with increasing tax rates that we have experienced a loss in the saving’s capacity, particularly with the establishment a hundred years ago, approximately, even more, of income taxes. And that’s something that began in a few countries and now it’s widespread all over the world. Then, in parallel to that, we have suffered the loss of private money – also called gold – which was also a very slow process which began in 1913 with the creation of a Federal Reserve and then in 1933 with the expropriation of gold in the United States, we’ve had a system – the gold exchange standard that lasted until 1971. From then on, we have been basically on fiat currency. That also led to a misunderstanding of the concept of liquidity. I think this is important. I’m going to put a few minutes here.

FRA: Sure.

MORTEN ARISSON: The way people look at liquidity today is as if it was an intrinsic characteristic of an asset. So, people can say: “Well this bond is liquid or this stock is liquid.” If you look at the way we used to see it – even until 1936 John Maynard Keynes, who was obviously not an Austrian… – He referred to the concept of liquidity preference. So, we all do have a liquidity preference, which is the preference to be liquid and to own money, which is an asset that sort of protects us from uncertainty. At the same time, the concept that liquidity is characteristic to an asset unfortunately was suggested by Carl Menger, who was an Austrian. He called that, in his words, “Marktgängigkeit” which was sort of “marketability”. And from then on, it was corrupted, and today we understand liquidity as the capacity of an asset to be traded with credit. If we say that a market is liquid, what we are saying today is that there is enough credit in that market to trade an asset, even though as a counterpart we don’t have true savings supporting that. And that is very important, because then, that creates a distortion that shouldn’t be. I mean, if you want to be liquid, Austrians would say, just own money that is the instrument that you need to be liquid. Then, from then on, if you want to invest, invest in capital assets. But the corruption of the concept of liquidity led us to mix everything – money and capital, and create degrees of liquidity in them, and forces to think in terms of paying for risk premiums when in fact there’s an asset available to us at every time, which is money. That too, because money began to be created by the expansion of fiscal deficits which led us to the misunderstanding of sovereign risk as well, – and it is something I discuss in the book. But all of that together created a distortion in favour of public securities versus private securities, the creation of Ponzis, and with central banks, systemic risk. At the private level the rationalization of all that under modern portfolio management – the theory of modern portfolio management. And all of this is a product of that movement in centralization that we have experienced, our big government that we have experienced since 1780s. In terms of Scientism, which can be described as the abuse of the scientific method applied to humanities, you can see that particularly after the 1870s with Walras, you have seen infinitesimal analysis, general equilibrium and the use of probability and the mechanistic view of interest rates that Austrians considered as inter-temporal exchange rates rather than as productivity rates, applied to the valuation of securities which are actually property titles on entrepreneurial processes. So all of that together takes us to where we are today.

However, I think we can make a pause here and think in terms of the 4 pillars of the Austrian School of economics. One of them I think is the most important is entrepreneurship – the role of entrepreneurship. It is completely ignored in mainstream economics; there’s no place for that because, mainly, it cannot be formalized, and that is seen as a disadvantage rather than being considered on a factual basis. There is no reason to believe it is better or not to mathematize entrepreneurship. And somebody, a few years ago, published an article on a Spanish magazine – Procesos de Mercado, edited by Jesús Huerta de Soto, proposing a way to establish whether or not entrepreneurship could be formalized. He concluded that it cannot, – because it’s non-recursive, it cannot. And so why did I bring this up? Because if you establish that human action cannot be mathematized, entrepreneurship cannot be mathematized, then there is no point in saying that you can value equity, which is a property title on said entrepreneurship. And that has profound consequences, because if you cannot value that, if it’s up to the risk management of the entrepreneur, the immediate direct consequence of that is to say that if you’re going to invest in equity you should invest in private equity because it’s something that you can manage. It’s a risk that you can manage. It’s an uncertainty in which you have certain control. And that is not the case solely with public equity. And one of the things I bring up in the book is that at the time of Adam Smith, with the beginning of the concept of limited liability, there was an enormous debate on whether it was advantageous or not for investing. One of the distortions that took us out from the field of private equity that was predominant, I would say, since the fall of the Roman Empire to the times of the trading companies in Holland, was private equity. And it was in the beginning of the trading expansion of Holland that lawyers like [Hugo] Grotius bought up the issue of changing the status quo and establishing the concept of limited liability. There was a lot of reaction against that at the time, and it had to be imposed. And because it was imposed and was properly seen as a privilege, the monarch that did that charged a fee on that privilege. And I would say it stayed that way until the mid-19th, century when increasingly in the United States it was seen as necessary to fund more ventures. But, like I say – it’s something very, very recent and it has created a distortion in terms of favouring public equity versus private. And at the same time, if you add the other intervention, which is the banning of insider trading, which takes the signal out of the market, it creates the illusion that there is no such thing as insider information –,… It also unlevels the field of private equity versus public equities.

So this would be one of the first pillars – the idea of entrepreneurship, that if you think the Austrian way, literally you think that the best case for you as an investor is always to go for private equity. The other one is the concept of probability. I think it’s a key characteristic of the Austrian School of economics to distinguish between case and class probability. The concept of class probability was actually the mainstream concept of probability up until the 1920’s. And I’m going to try and be brief here, but it basically was the probability that – you can think of in terms of when you roll the dice [here are limited spaces and you know the outcomes. Richard Von Mises, who was the brother of Ludwig Von Mises, wrote a book called “Probability, Statistics and Truth” that I think was published in 1928, and he made the case that that is the only time when one can speak of probability correctly – properly. And that means that, in order to do so, you have to identify a collective, a group of elements or, in this case companies, if you want. And they have to behave in a homogeneous way and converge to a number that you may be looking at, let’s say a return or a ratio. And most importantly, whenever you take different time frames to see that convergence take place, regardless of which time frame you take, you still see that trend taking place. And if you apply that to investing, you will realize that since entrepreneurship is unique – there are unique markets, there are unique companies with unique management, unique capital structures, it’s impossible to apply probabilities here, because, – I mean you can speak of a asset class called equity versus an asset class called debt and I guess you could say that the convergence of the net returns is positive otherwise there would be no entrepreneurs – otherwise they would be always bankrupt. But besides that, I can’t think of any other case. And the proof of that is that rating agencies show every month updated tables on, for instance, migration in risk ratings. I mean, if you could apply probabilities here regardless of which timeframe you see, probabilities of default for, let’s say companies with similar debt-to-equity or similar net debt-to-ebitda ratios, it should not change, – but the fact is that they do change… I’m not surprised. And it’s just, you know, with that scientist approach, with that search for perfect information, you run into the illusion that we can use it.

But it was a movement that began with Keynes in the 1920’s in a book called “The Theory of Probability” and it has really shaped the way we look at portfolio management today. If you use a Bloomberg terminal and you try to value any security that would be a derivative or any structured product, you would immediately see that probability is used without thinking, without a pause. It’s just something very direct. If you use the other concept, the Austrian concept of class probability you realize that unless you actually have control over that security that you want to own for your investment purposes, there is no point in trying to forecast the probability of something happening, because effectively you have no control. I mean you’re running into a tautology where you tell yourself: if such and such a thing happens, I would get this outcome. But I mean, that adds no insights – no further information. So, I don’t know if you have any questions or, if you want, I can go to the 2 other pillars of…

FRA: Yeah, sure. So we’ve covered so far entrepreneurship and sort of the correct theory of probability and we have two more institutions, money, capital and interest rate. Go ahead on those two.

MORTEN ARISSON: In terms of the institutions, I think that the Austrians have an advantage because they can understand the institutional context in which investing takes place. I mean, there are very important institutions like a deposit and a loan that the Austrians can distinguish. They understand that a deposit is not a loan, and that fractional reserve banking corrupts that concept today. They understand what is money and what it’s not, and the qualities that money has to have and that gold is money, so to speak, because it has all those qualities. If you look at, for instance, virtual currencies, I believe that virtual currencies lack two qualities that are quite necessary – I mean fundamental to money. One of them is fungibility. Since Bitcoin by definition is a ledger, a distributed ledger, it will never be fungible.

FRA: Sorry, just to clarify, the virtual currencies you’re meaning the cryptocurrencies right? Such as Bitcoin and –

MORTEN ARISSON: Right, right.

FRA: Okay. Just to be clear.

MORTEN ARISSON: Yeah. So those cryptocurrencies are distributed ledgers. There’s a reason why that happens, because they are not redeemable. So, the two characteristics that define money – I mean that are more but these are fundamental to money: these are fungibility and redeemability. And by definition virtual currencies or cryptocurrencies are not redeemable. You cannot redeem them into any… – you can change them, you can use them as an indirect medium of exchange, but you can never redeem them themselves. Fiat currencies you can do, you get the physical paper bill. Gold you can do, you get the metal. But that’s not the case [with cryptocurrencies] and because possession is not there to show ownership –, Ownership has to be established via the distributed ledger. And that institution [distributed ledgers], if you want, because it has been a spontaneous creation of the market, cannot benefit from fungibility, by definition, because at any point you know what belongs to whom.

FRA: Yeah.

MORTEN ARISSON: So, there can never an established capital market in that sense. And as far as I know, at least to date, the only inter-temporal exchange is peer-to-peer, right? Which some savings are – you know exchanged from one participant to the other, but not to a central institution that collects and then distributes. And I mean that is intrinsic to virtual currencies precisely because .. my understanding that those who created them, actually wanted to avoid that centralization, – But banking has a role, right? I mean, there’s a lot of information to be discovered about those saving and those demanding those savings, and it has value. And banking itself is an institution that has been documented at least since the time of ancient Greece. So, without fungibility you can never have capital markets in cryptocurrencies. And at the same time without the redeemability if there ever is any sort of expansion via credit multiplier, it will have to be unchecked by definition too, because there will be never any run on any Bitcoin banks, for example. And eventually Bitcoin or any cryptocurrency that advances to that stage would devalue. You know, defeating its own purpose, right? Because the credit multiplier would affect an expansion that was not thought of by the traders of the cryptocurrency. So, if you want, you know, in a way you can say that Austrian investing is institutional arbitrage, because you’re always understanding loopholes, interventions on market-driven creations, institutions and arbitrage and sell the bad ones to buy the good ones. You could say the same about structured investments, you could say the same within the space of currencies” you’re arbitraging certain features. Usually scarcity being one of them, we arbitrage scarcity when you see that a currency expands more than another, you’re arbitraging scarcity. If you need to take capital out of a jurisdiction that is pretty restricted, you are arbitraging redeemability. And that’s where Bitcoin gets its value [from], because it’s less redeemable and at the same time less sizable by the authorities.

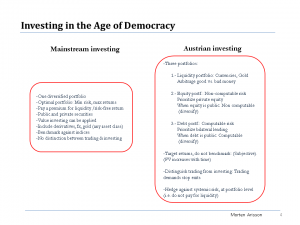

There is also the issue of public institutions where you recognize, if you are into the Austrian School of economics, you recognize failures in public institutions. One of them is the Eurozone, where mainstream economists took last year’s crisis as a liquidity crisis, while lots of other economists understood that it was an institutional problem and that it was the fact that there’s not a unified bond market in the Eurozone. And the last but not least important of all the pillars is the understanding of what is money and what is capital that is lacking in mainstream Economics. And that interest rate is actually an institution too, whose function is to allow the inter-temporal exchange of resources between people. And the direct consequence of understanding that is that it allows you to differentiate when you invest and when you trade. When you invest is when you exchange your money for capital assets. And so with derivatives that are not used for hedging, for instance, or commodities or fiat currencies, you’re not investing, they don’t yield any produce and that’s the same case for gold. So an Austrian would say that you do not invest in gold, you exchange a fiat currency: one currency for another one. There is also another direct consequence of understanding what an interest rate is, which is that asset allocation is nothing else but inter-temporal preference. So, there’s a direct connection between your inter-temporal preference and the way you allocate your assets, whether you want growth or not. If you want growth you need, like I said, to invest in equity, in entrepreneurial projects. If not, if you want yield, obviously you will go for another part of the capital structure – for debt. And any subjective exchange – I mean any, inter-temporal exchange is completely subjective. There’s no point in trying to benchmark yourself against indices in terms of returns. You have to target your absolute returns, the ones you are comfortable with and the ones that are consistent with your liquidity preference and I’m going back to the concept of liquidity. So that when you put all these four pillars together: the correct understanding of the theory of probability, the correct understanding of the role of entrepreneurs, the correct understanding of the role of institutions, and the correct distinction between money and capital, and understanding of interest rates, then you come up with a particular method that would say to you: Well, you need to think of investing not in the terms you have seen until now, where you have one big diversified portfolio that tries to be optimized in terms of risk and returns, minimizing risk and maximizing return.

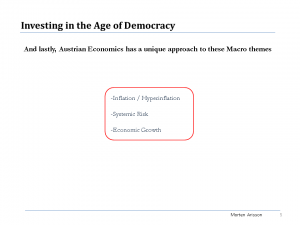

You shouldn’t be paying a premium for liquidity. You shouldn’t mix private and public securities. You shouldn’t even try to do any value investing because it’s a tautology. You will never be able to really know the value of any entrepreneurial project unless you have a control of it. And then, the first thing you should do is define your liquidity needs, so your liquidity preferences and separate that into a liquidity portfolio. Then, the second one is, once you establish your inter-temporal preference, you look for a certain component of growth and a certain component of yield and that growth will be represented by equity. But you have to prioritize private equity and in terms of that the same happens once you prioritize bilateral loans. But again the book goes to explain all the distortions that we have suffered that have made the use of bilateral loans, such as lending to someone directly via mortgage, – that took us away from that. We are left with public securities, public equity and public bonds, and we are constantly benchmarking the indices. There is another interesting thing; if you recognize the fact that final value increases with time and the direct consequence of that is that – most of the time with mainstream investing theory – the recommendation comes that when you’re young you should try to go for as much equity as you can for as much growth as you can with your investments, because only after when you’re established you need a stable cash flow. But when you think of that, you are putting yourself through an enormous amount of risk, uncertainty in securities over which you have no control and you lose an enormous amount of compounding value. So, I think that when you go through all this thinking in terms of how to approach investing, one conclusion is that the longer your term horizon, that means, the younger you are, the less you have to invest in equity and the more you have to invest in computable risk that can compound – that you can manage. There were a lot of institutions that we had created before this big increase in government. One of them was the annuity business by the insurance companies. It was a legitimate market-driven, spontaneous invention, but today we don’t have that and with distortion in interest rates it’s pretty expensive if you try to go that way. So, again, the younger you are the more you have to allow for that compounding to work for you. Only when you’re getting older and you see that you don’t get to your target in terms of savings, then you can start risking something, which is completely counterintuitive versus what common knowledge says. So, and after all, yes I devote one third of the book, the last third of the book, to discuss the proper macro themes in Austrian economics. But, as you can see, we just discussed very specific things and I haven’t gone properly into discussing any macro themes. And one of them, I think is most important, is systemic risk, in the chapter where I go to show that there is no such thing as systemic risk. It [systemic risk] is just the natural outcome of the interventions in the market by central banks. The fact that we don’t know when it’s going to happen doesn’t mean it is risk. It is there, and we know it causes, and we know how the process works, the coupling between central banks works, which I describe in a chapter, via cross currency swaps. And I recommend that after you have established your three portfolios, liquidity, equity and debt portfolios, one can think in terms of an aggregate hedge against that systemic risk at the portfolio level. That could sort of address the mainstream view that you have to pay a premium for liquidity. An alternative could be that you do not, again, you separate whatever liquidity you need under your liquidity portfolio. Then once you have established your investing portfolios you put a hedge against systemic risk for them, to protect them.

FRA: And how do you do that exactly in terms of applying a hedge?

MORTEN ARISSON: This is just my own opinion, in the case of Canada that the hedge was the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the Canadian dollar. As you see, increasing systemic risk in these particular times, in this particular moment, through the increase in risk from the real estate market, I think that will be translated into sovereign risk and it would push the monetary authorities to devalue the Canadian dollar. So, if you can be long an instrument that would capture that and would have some convexity properties in that sense, then you’re doing exactly that [hedging systemic risk].

FRA: And just a couple questions. You mentioned on the equity portfolio that you should prioritize private equity. How do you go about doing that in terms of the prioritization process?

MORTEN ARISSON: I think the simplest way to do that, which is accessible to everybody, is to buy a property today. But that has been completely intervened today by the government. There is this push from the government to take you away from any safe haven assets. When you buy a property for investment purposes, obviously you are first avoiding fractional reserve or re-hypothecation of the assets, because there cannot be two similar assets on the same location, because you’re buying location. Then you are free to manage – you have a lot of latitude in terms of managing, and in terms of having control over that. But for real capital assets, I have a chapter devoted to them, but I think the conclusion in the book is that there is never a definitive answer to that. And that is very intrinsic to Austrian Economics: the notion that there is never equilibrium; that you’re always in danger, that you always have to look out for opportunities and for future problems. Like I said, there might be multiple real capital assets. You can have property, cattle, wine, forestry, and farmland. And all of them they serve a purpose at a specific time within a crisis. For instance, in terms of farmland, it’s not a hedge against crisis forever. It will be your equity investment, but to a certain extent if things go really bad, you will be stuck with an immovable asset, a very easily taxable asset. So again, even as I provide examples of ways in which you can invest into private equity, there is never a safe haven asset.

FRA: And in terms of public equity, is your suggestion to diversify due to the non-computable risk?

MORTEN ARISSON: Yes and no. If you say that then anybody could argue well you’re just saying the same as mainstream economics. And here’s the thing: in Mainstream Economics, the exercise of diversification is against the…they have what they call systemic risk component that they claim to be able to measure from observations on what they call risk-free assets, such as sovereign bonds. That diversification comes from the measurement of the sigma, the volatility of all their assets and their correlation and so on. Which again, they go into a circularity because they assume that past performance will be something that you can project into the future and you have to make a lot of assumptions that just revolve around themselves. What I am saying is, yes you have to diversify, but only because you know nothing. You absolutely know nothing and the shot can come from anywhere. If you tell yourself that you need 20 securities to be diversified, well you’re kidding yourself, that is not the case. If these are subject to a currency zone and they are denominated in a currency that because of institutional problems, because the central bank is too weak or prone to suffer from devaluation – there is no remedy to that. So, the diversification comes only as a consequence of the recognition of our ignorance, but only that. I cannot provide you with a specific number [of securities to diversify]. Obviously, the general idea is that all things equal, the more assets you have, the better. But that is not necessarily true and that [diversification] is a very subjective exercise.

FRA: The last question is on – you mentioned these three macro themes and how Austrian Economics has a unique approach to these three macro themes. Can you briefly touch on the inflation/hyperinflation macro theme?

MORTEN ARISSON: Yeah, sure. Obviously the general notion of inflation within mainstream economists is that you have something that is observable, that is a vector which they call an index of prices and that inflation is neutral, that never goes up or down in terms of monetary expansions or reductions. But as an Austrian you recognize two things. First, that it is not neutral, absolutely not. The reason that money expansion is not neutral is precisely what motivates monetary authorities to create, inflation. The second thing is that there is this notion that hyperinflation is simply an arbitrary high number in terms of inflation, and that is not the case. Hyperinflation is not quantitative – that is my point. Hyperinflation is a qualitative phenomenon and it is one in which the central bank finds itself defenseless, in a circularity where they are obligated, they are forced to issue an interest-paying liability. The interest that they pay on the liability is higher than any interest they receive on their assets so that [resulting] deficit, which is called quasi-fiscal deficit, can only be covered by monetizing and by printing money to pay that net interest. Then again, in order to take that money that the central bank just put into circulation, what they have to do is increase the rate, they have to sterilize that money that they have just printed, at a higher rate, which simply enhances that circularity. Today, right now as we speak, there is one country that is suffering from that – Argentina. With an instrument called Lebacs, the central bank began paying something like 38% a year ago and it’s around the high 20’s now. And, unless they have the fiscal deficit in control in Argentina, that will spiral out of control. So, even though you don’t see inflation in the 100’s like you used to in the 80’s maybe, the fact is right now that that central bank is out of control, and they’re in the early stages of a hyperinflationary process. What about us in the first world? Well, what matters here is the relation between the interest income received by the central bank in excess and what they have to pay. It doesn’t have to be too high. What if there was a sovereign problem in the Eurozone and all of a sudden the central bank had to replace sovereign bonds with their own liabilities? Right now what they do is they collateralize, but, what if they actually had to replace it with their own liability, but with an interest-paying liability? On the one hand they have, like any central bank, money supply which bears no interest and then they have to pay 25 bps. Those 25 bps will have to be monetized. So, right there, you have hyperinflation, and I think one has to pay close attention to that, and only if you understand that you will see how, in my opinion, we are at the early stages of a hyperinflationary period. But again, you have to understand that it is a loss of control by the central bank [what causes hyperinflation] and not the inflation rate on its own.

FRA: Wow Morten, great insight on Economics and investing. How can our listeners learn more about getting access to your book “Investing in the Age of Democracy”?

MORTEN ARISSON: The book is already on available now on Amazon. It is under the title “Investing in the Age of Democracy”. And soon, I intend to put it on a digital format for Kindle.

FRA: Great, we look forward to that. Thank you very much Morten for being on our show.

MORTEN ARISSON: You’re very welcome.

Transcript by: Daniel Valentin <daniel.valentin@ryerson.ca>

LINK HERE to get the podcast in MP3

08/28/2017 - The Roundtable Insight – Morten Arisson On A Unique Investing Method Based On The Austrian School Of Economics

08/28/2017 - The Roundtable Insight – Morten Arisson On A Unique Investing Method Based On The Austrian School Of Economics