FRA is joined by George Bragues in discussing his book Money, Markets, and Democracy: Politically Skewed Financial Markets and How to Fix Them, along with a thorough overview of the Austrian school of economics.

George Bragues is the Assistant Vice-Provost and Program Head of Business at the University of Guelph-Humber, Canada. His writings have spanned the disciplines of economics, politics, and philosophy. He has published op-ed pieces in Canada’s Financial Post. He has also published a wide variety of scholarly articles and reviews in journals such as The Journal of Business Ethics, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, The Independent Review, History of Philosophy Quarterly, Episteme, and Business Ethics Quarterly.

FRA: Just thought we’d begin with the book that you have: It’s called Money, Markets, and Democracy: Politically Skewed Financial Markets and How to Fix Them. Can you give us an elaboration on what the basic messages are, the themes of your book?

BRAGUES: Sure. The key thing I wanted to get across in my book is the importance of politics for understanding the financial markets. This is something that gets often missed in your typical courses that are taught at the MBA and also the undergraduate level. When a student takes a course in investment finance or financial economics, they don’t get exposed a lot to the political factors that drive prices, that drive trends, that drive decisions of monetary policy and interest rates, as was made abundantly clear with the 2008 financial crisis. Though one could have seen evidence of the role of politics in finance earlier than that, but it became much more obvious after 2008. This is definitely a gap in the way financial markets are taught to students, and the way they’re discussed by economists in general. The book is designed to address the flaw that the economics professor tends to be the only one that studies the financial markets. The dominate it, they practically hold the monopoly in it, and other disciplines, specifically politics, need to be part of the mix.

As the title suggests, it’s not just politics per say, or politics in general that needs to be considered, but the regime. The regime is defined as the fundamental rules of the political game. This is actually a term that comes from the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. He wrote a book – still very well known, still discussed among political philosophers – called The Politics and he distinguishes regimes into three types. He distinguishes it by who rules: if you want to know what a political system is like, you ask yourself who’s running the show, who’s making the decisions. Three basic different types of regimes that are possible: ruled by the one, which we would call autocracy or sometimes monarchy or dictatorship; there’s ruled by the few, which we would call aristocracy or sometimes oligarchy; and then there’s ruled by many. Democracy would be the example of that.

Financial markets around the world today, with only a few exceptions – China primarily among them – most of the major financial markets today are operating within democratic political contexts. The argument I make in the book is that democracy, because of the political incentives that it imposes on politicians because the values – the types of norms and morality a democracy has, these two factors, the value system and political incentives, what politicians need to do to get elected in a democracy – these fundamentally structure the nature of the financial markets. They don’t do it necessarily on a daily basis, you can’t day trade on this information or even swing trade on this information, but it definitely will illuminate anybody who’s involved in investing on the financial markets to help them better understand the force that drive prices over the long haul.

So my thesis is that democracy, while probably the best political system relative to the alternatives, despite it being the best of the available alternatives, it does create problems in the financial markets, it does distort the ability of the financial markets to do social good, and so a lot of the problems that we have are because of the fact that the markets are operating in a democracy.

FRA: How does that happen? How does democracy distort the financial markets? Could you give some specific examples?

BRAGUES: The big example that I discuss in the book is the money supply. The main argument that I make is that democracies tend to oversupply money into the economy, and that has an impact on the financial system. I distinguish two factors that drive democracy’s overproduction of money, this excess liquidity. One factor is this class conflict between taxpayers and tax consumers. This notion of a class conflict between taxpayers and tax consumers is a notion within Austrian economics and it is meant to replace the Marxist view that the fundamental class divide in society is between bourgeoisie, the capitalists who own property, and the labour working classes who don’t own property. The Austrian view is that the main class division is between those who on net pay more taxes than they receive in services from the government – this group would be the taxpayers – and the tax consumers are those who on net receive more from the government than they pay. In terms of what a tax consumer can receive, this can range to anything from unemployment insurance payments, social assistance payments, favors provided by the government in terms of inhibiting competitors in your industry. The argument is that in a democracy, if a politician wants to get elected, the name of the game is to get 50%+1. Given that the distribution of the income in modern commercial societies tends to be such that there’s a few rich and wealth tend to be a small segment of the population, and the middle class and lower classes tend to be the majority, the best way to get elected is to offer mostly the middle class all sorts of public goods in terms of social programs and so forth, and then have those financed by the well-to-do who would function as the taxpaying class. That way you get your majority and get elected.

All politicians, whether the left or the right, both sides of the political spectrum do this. Perhaps the left does this with a bit more conviction guiding their efforts, but on both sides of the political spectrum this happens. So politicians engage in this bidding war every time election time comes, trying to offer the majority all these goodies with the idea that they don’t have to pay for it, someone else will. What ends up happening, I argue in the books, is that after a while of this bidding war where politicians offer more and more public goods, someone has to finance this. Eventually you run out of taxpayers or you run into taxpayer resistance. At that point politicians then resort to the bond market and the bond market has proven historically quite eager to lend funds to the government. Government bonds are very attractive investments for a lot of folks because of the safety. This is money that’s backed up by the power of the state, unlike corporate bonds which are not. Corporate bonds are only paid ultimately if the corporation is successful at attracting people to voluntarily buy their goods and services.

I argue in the book that we now have a kind of financial market-government complex, or a bond market-government complex. The bond market has emerged as a kind of handmaiden to the welfare state, this growth of government. At a certain point, even the bond market will say ‘we can’t lend more’ and at that point politicians will appeal to the money press and they will enlist the central bank to print money, essentially, though it’s more complex how liquidity is injected into the economy, but that’s basically what happens. So essentially democracy leads to fiscal profligacy, too much spent relative to the revenues politicians are willing to collect from people. They then have to go to the bond market; public debt rises. And then to increase their options of financing this deficit that is inherent to democracy, they require control over the monetary supply. My argument in the book is that the gold standard, which existed for a good part of the 20th century in one form in another, which ultimately ended in the early 1970s – August 1971 if you want to get exact – that was in a way written in the DNA of democracy; that democracy ultimately is intentioned with a monetary constraint like the gold standard. That’s one of the ways I make this argument that democracies do damage to the financial markets.

(click to expand)

FRA: It sounds like the endgame is either a no bid situation in the bond market, or as you mentioned they could go to the printing presses. The other endgame is the loss of purchasing power in the currency. Either way, I guess that’s likely to be the only way to stop the politicians’ continuous profligate spending.

BRAGUES: Either the bond market has to say no, and historically as mentioned before they’re not very good at saying that. In the book I discuss the historical record of the bond market’s ability to keep governments to account. I remember in the past, I think he’s still around, Ed Yardeni coined the term ‘the bond vigilante’, which was a popular term in the 1990s. The bond vigilante is this creature that’s supposedly watching over governments, closely scrutinizing budgets and if they see any sign that they’re letting public debt out of control these bond vigilantes then start selling off the bonds of the country that’s engaging in this poor fiscal policy. The record, especially with developing economies, is that bond markets only react to excessive public debt very late in the game, when it’s become quite obvious and traders seem very eager to provide money to governments who are spending above their means while the debt is building up. And only when a certain threshold is hit – it’s really hard to find that threshold, Kenneth Rogoff wrote a book a few years ago when he went through the history of it and said, well if it’s a developing country it appears to be about 60% of GDP, that’s when the bond vigilantes come out; developed countries tend to have more tolerance. Even that threshold doesn’t seem to have held, because we now have countries – Japan principally among them – they’re well above 100% GDP and there’s no sign bond markets are growing less willing to finance their debts. The bond markets will have to have a shift in how they approach their investments into bonds.

(click to expand)

The other constraint would be the gold standard, but as I talked about in the book, I don’t totally foreclose the return of the gold standard. I agree that we should try to do as much as possible to bring that back, but democratic politicians don’t want to have the constraints posed by a gold standard because it makes their lives difficult. It means they have to say no to people, it means they can’t win elections by simply promising all sorts of goodies. It’s no surprise to me that the gold standard ultimately disappeared as democracy progressed.

FRA: You’ve included a number of slides, including one slide with a quote from James Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer where he highlights that you not only diagnosed the problem but also proscribed a solution to the problem. As you mentioned on the gold standard, what you’re saying is while not likely to happen, or not likely to come about, you do identify the solution. What is more the endgame: no bid in the bond market or gradual loss of purchasing power in the currency?

(click to expand)

BRAGUES: I would probably say the latter. Especially with the next 20-40 years or so, you have an aging demographic, a greater proportion of people who are older and they will seek safety, and I think that keeps up the bid in the bond market. I would say we have very slow decrease in purchasing power.

The thing is, in part of 1954 inflation was practically nonexistent. You’d have inflation only in certain periods, usually after a war, after substantive crisis, when the government is compelled to appeal to the monetary press to finance conflict. If you look at the data from early 19th century to 1945, I think in Britain for example there was really no change in purchasing power. The Pound was worth around the same in the early 19th century as it was going into the early 20th century. But that’s all changed since 1945. We now live with a situation which we think is normal, but which from a grander scheme of things is not, and people in democracy seems to be willing to live with an inflation rate of around 2% a year. I think governments are going to try to keep that going and if necessary, perhaps tolerate a somewhat higher rate – 3,4,5%. Some economists have talked about that, tolerating a different rate for inflation rate. I think all the incentives are for politicians to continue to take advantage of the bond markets’ generosity, if you want to use that term, and try to finance this via the inflation tax at the highest level of tax that is possible without incurring significant public protest.

FRA: I think we’ve seen figures of if you have inflation at 4% a year for 10 years, it can reduce the burden of debt by one half, something like that.

BRAGUES: Yeah. If you look at history, when we look at how the debt after WWII was dealt with, it was a form of financial repression that took place, where the inflation rate was held higher than the rates that most people be able to gain on deposit. I think they’ll try to appeal to that strategy again.

(click to expand)

FRA: Yeah, very likely. Just switching gears slightly, we’ve talked about the Austrian school of economics and you’ve also provide a set of slides on the investment potential of Austrian economics in investing. Just wondering if you can give some highlights of those slides and how you see the Austrian school of economics compared to the Keynesian school of economics.

BRAUGES: In terms of Austrian investing, I think it’s a promising approach. In order to succeed in investing, you do need to have an approach that is different from other people because if you’re just doing what everyone else does you’re just going to get at best the average rate of return. You’ll get the same rate of return that you might, say, if passed an investing vehicle like an index fund minus the cost of running your investment, the commissions and so on. Because most people in the financial markets are essentially Keynesians – they may not be conscious fully of their beholden to Keynesian principles, but anyone who follows the markets on a regular basis, specifically on issues of how the Federal Reserve or ECB is expected to react to certain data points, it’s clear that when you see a lot of these analysts get quoted in the Wall Street Journal or the Globe and Mail and so on, that they effectively are operating with a Keynesian worldview. In terms of having a unique point of view that can offer above average returns, I think Austrian economics offers something certainly worth looking at.

In terms of what it boils down to, I’m the first one to admit there’s not set Austrian approach. You can have five Austrians in a room and they’ll have five different approaches, although they’ll come from a common base, that common base being the commitment to certain Austrian economic principles. I say the two biggest ones that are relevant in terms of investing are A: the rejection of the efficient markets hypothesis, which is very common in the academic treatment of finance even though it’s losing some of its support to another field called behavioural finance, which argues that psychology needs to be considered in understanding how markets move. Efficient markets hypothesis still looms large, especially in academia, and it argues that in any point in time prices reflect all available information so that everything that is known or can be known is already in the price. So there’s no point doing any sort of analysis to try and beat the market if you believe in this theory because everyone else has already looked at the financial statements, they’ve already considered the company’s strategy, already looked at the technicals and moving averages and trend lines and all that, it’s already in the price.

(click to expand)

The Austrian view rejects EMH and it’s because of its theory of entrepreneurship. Austrians are very big on the notion that what drives economic activity and specifically economic growth is the activity of entrepreneurs. What entrepreneurs do is they find arbitrage opportunities; they find profit potential that other people aren’t seeing. We can transplant the entrepreneurial function to the financial markets and say that there are similar arbitrage opportunities, similar opportunities that people aren’t seeing, that with good analysis and some work can be grasped. That’s point number one that differentiates the Austrian approach from more mainstream approaches that are taught in academia.

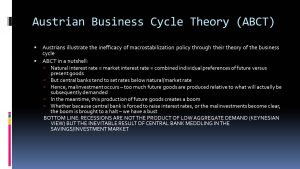

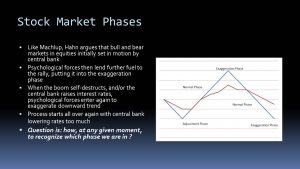

The second component that differentiates the Austrian approach from academic and certainly Keynesian approach, which tends to be dominant among financial market practitioners, is the notion of Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT). This is the argument that central banks, through their policies in terms of money supply and interest rates, artificially induce booms and busts. Booms and busts are not on the Austrian view as simply sort of random events, facts of life of capitalism, or caused as some of the old Keynesians would argue by a lack of aggregate demand. They would argue that the reason we have bull markets and bear markets is large in part because of the actions of central banks. They would argue that central banks have a tendency to run overly loose monetary policies because all of the political incentives are there for that and reinforces that. What happens is that they tend to set the interest rate below what’s called the natural rate. The natural rate would be the rate that the market would set if the interest rate market were free, which it is not when you have a big central bank regularly intervening in the money markets. The argument is that when interest rates go below the natural rate, whenever they’re below what the market would dictate, it gives false signals to investors that future goods, goods with long term – real estate would be the classic example here, but also technology stocks, anything where the payoff is way in the future – those kinds of companies, companies that engage in those products, tend to get overbid. Too much investment tends to flow there and the Austrian view is that this will initially sustain a boom, especially in these areas of the economy, but then at some point one of two things or a combination of both happens: either people realize these investments are not going to work out, that the demand isn’t going to be there, that these future goods everyone’s producing for there isn’t going to be sufficient demand for them so you get a shakeout in that industry. Or two, the central bank decides to tighten monetary policy cause they can sense that things are getting a little too frothy, or a combination of the two. Then you have the bust and the market goes down. The idea is then the central banks will come in while the bust is taking place, aggressively lower interest rates to try to revive things, and the whole cycle starts over again. That’s probably the most important component to the Austrian approach of investment, this acknowledgement that central banks are the ones ultimately behind the longer term ups and downs of the market.

(click to expand)

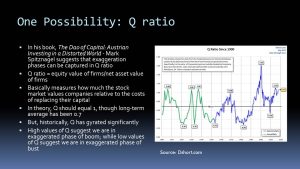

FRA: In terms of other indicators or other aspects of the Austrian school that could help investing, you mentioned a few here like the Q ratio from Mark Spitznagel?

BRAGUES: Because the Austrian school recognizes there are going to be different phases of the stock market where things either get overvalued or undervalued, then the question arises, how do you recognize when we’re in a phase when things are overvalued and where things are undervalued? One approach has been put forward, by Spitznagel as you pointed out – his book is called The Tao of Investing – and he argues that we look at the Q ratio. The Q ratio goes back to James Tobin, a Keynesian economist. Tobin’s Q ratio is based on the numerator being the market value of companies, roughly stock market capitalization, divided by their real asset value, measured by the replacement cost of the assets of the firm. So basically you’re looking at the Q ratio measures how much it would cost to buy all the companies on, say, the S&P500, and you take that number and divide it by what would it cost me if I were to replace all the assets, going out into the real asset market and trying to replace all the assets that are on the balance sheets of S&P500 companies. In theory, it should be 1. That is to say, the market should be valuing the assets at the replacement value. That way you get avoid an arbitrage opportunity. In theory if the market value is higher than the replacement, you can sell stocks and buy the assets. Conversely, if the market value is below the asset value you can buy shares and sell the assets. Historically that ratio has been around 0.7, so Spitznagel suggests we use that as the anchor. If you’re about 0.7, that is suggestive of an overvalued market, and if you’re under 0.7 that would suggest an undervalued market.

Currently I looked at that ratio today and it’s 1.07. It’s not the highest that it’s been historically; it’s been as high as 1.78 in the early 2000s at the height of the Dot Com boom. Currently at the 1.07 level it’s at similar highs at other turning points if we just take the early 2000s out of the picture. If we look at early ‘70s was another high, another high was just before 1929. If you look at the Q ratio that is suggestive that we may be at a key inflection point here. My only concern with the Q ratio, just like I would have any concern with any other fundamental type of metric, whether it’s P ratio or price-to-sales ratio or peg ratio, is that they can show for a long time that an asset is overvalued or undervalued, and if you were to take a position in accordance with that signal it could take a long time for it to actually go in the predicted direction. It’s a notorious problem with these kinds of signals, so I suggest that Austrians can apply technical analysis and the approach here would be you use some sort of long term moving average – this would be just one technique among several that you could use to gauge the long term trend – and you take advantage of the trend and you wait until the trend is broken. If you’re using, say, a 10 month moving average then you wait for the index – here the S&P500 – to close below that average at the end of the month and that would be your signal that, okay, it’s a frothy market but other people are recognizing it, it’s not me with my Austrian analysis and now that the market seems to be coming to realize what’s going on I will get out. And conversely when things are looking undervalued. So an Austrian analysis could tell you things are looking undervalued now, the bust has perhaps gotten a little too far, people have gotten a little too fearful, a little too anxious, but you wouldn’t immediately go in. You would wait until the market went about the 10 month moving average.

(click to expand)

I would argue this would avoid the problem of using something like the Q ratio or some sort of P/E ratio. You could also use the 10 year P/E ratio, which is like Shiller’s – Robert Shiller has that indicator – that you allow the market to tell you when the trend is over, when the frothiness is really done. I’ve done some back-testing on; it seems to work fairly well. There’s also a number of people out there that follow this method, but most people follow the method of just look at the moving average; they don’t come to it with an Austrian understanding of where the market is temperamentally, as it were – whether it’s undervalued or overvalued, just looking at pure trend.

FRA: Another aspect of the Austrian school would be the focus on stores of value. You mentioned you have a slide here about gold, if you want to talk to that a bit in terms of how that can play into a store of value.

BRAGUES: Sure. One thing that Austrians can sometimes fall into the trap of is becoming excessively pessimistic. There are good reasons to be excessively pessimistic when one considers the fiscal state of our governments, and that what central banks have been doing to finance that fiscal profligacy. The reality is that markets seem to do different things that what some Austrians who are really negative would predict. Spitznagel makes this point in his book as well, that Austrians need to be careful of getting a little too pessimistic. That might translate into going into 100% gold; I would not be in favor of that going into 100% gold position. I do believe that it is a good store of value, to use your phrase, and at least some portion of one’s portfolio should be in gold for several reasons:

We really don’t know how this whole thing is going to play out in terms of these highly indebted states and central bank excess liquidity that’s been provided, so we’re not sure how that’s going to play out. It could play out very ugly; my Austrian friends are among those that are very negative and they may turn out to be correct. You want to have a position in your portfolio where you profit from that, or you protect yourself from that. Also two, if as I expect, we’re going to have this continuous slow reduction in purchasing power, whether it’s 2%, 3%, 4%, whatever it is, that does have a long term impact. That does compound and gold has proven able, when looked at form a longer term trajectory, to preserve your purchasing power against that.

(click to expand)

I just did this calculation today, but if you look at the returns of the S&P500 index, total returns assuming you invest all your dividends? From 1971 when the gold standard ended and you compare it to gold, I think there’s only about a—If you put your money in the S&P500 and invested your funds when the gold standard was abandoned in August 1971, you would have made about 10.38% a year, just over 10%. If you had just put it in gold, you would have been at 7.58%. So you’re only looking at about just under 3% differential. That’s not bad. Gold is… You’re not risking your money and businesses, when you invest in gold you really can’t expect that you’re going to earn a risk premium that a firm would typically be expected to earn for assuming risk in the marketplace and offering goods and services. There’d only be about 3% behind, and this is from the current day when gold is relatively low and well off its highs from 2011 and the S&P500 is at near all-time highs. Right now this calculation is very much favoring the S&P500 but over time gold doesn’t do too badly, even though things right now might not look too great in terms of its performance vis a vis the S&P500 index. But looked at it from a longer term? It does trail, but you’d expect that because the S&P500 is a different kind of investment; you’re investing in companies and there’s a risk there. You should be compensated for that.

From a crisis protection point of view, and also from a protection from this continuous reduction in purchasing power, I think that argues for some proportion of portfolio being in gold.

FRA: Excellent comments, excellent view. I guess to close out, if we take the Austrian school of economics and the basic messages and themes of your book on money markets and democracy, how do you see the situation today in terms of perhaps the millennial generation? Where they’re going, where they’re leading politics with respect to economics, finance? What are the millennial views and perspectives on the economy and financial markets currently? How are these views being formed by political, financial, and economic trends?

BRAGUES: The millennials… That’s a pretty slippery term to define; we’ll go with 18-29 year olds. This has been a talking point for the last year or so and it’s certainly became a major point of discussion with the success of the Bernie Sanders campaign – they didn’t win the nomination, he didn’t win that, but he certainly put forward quite a battle to Hilary Clinton. There was a survey done by Harvard University, it came out just over a year ago, which showed that millennials in the United States – so these are young people from 18 to 29 – for the first time since they’ve been doing surveys, that a majority of them no longer supported capitalism. The number was actually 51% no longer supported capitalism, 42% still supported capitalism – I’m not exactly sure with the remainder, I’m assuming they were undecided. Certainly with Bernie Sanders, who is a self-professed socialist or social democratic or ‘democratic socialist’ as he put it, certainly this played out politically. This is a concern though we shouldn’t make too much of it, but it is definitely a concern. I think the reason why we should not overplay it is that traditionally young people have veered more toward the left. If you look at voting patterns, for example Britain, the likelihood of someone who is young voting Conservative – I’m not saying the Conservative Party in Britain are perfect pro-capitalists or pro-markets, but they’re more likely to be pro-market than the Labour Party on the left on the political spectrum. Going back to the end of WWII, younger people were much more likely to vote for Labour or for some other party on the left than for the Conservative Party. As people get older, they tend to veer conservative. There’s this saying that if you’re not Liberal before leaning left when you’re under 30, you have no heart, but if you’re still Liberal after 30 you have no head. It nicely captures out how age affects political and ideological affiliations.

When we consider that, that means we should moderate some of our concern, but it’s still a concern. The question arises, why? I think there are a number of reasons: one is they’re just young, they’re more moved by their passions, morality is very much implicated with their passions or moral sensibilities and young people tend to be quite idealistic. When you look at capitalism, it – at least on the face of it, I wouldn’t say this is the definitive interpretation of it – it looks like it’s driven by selfishness or self-interest. If you’re idealistic that’s not a good motive to have, that’s not a good motive for society to be energized by. That, I think, is a factor that leads the young away from capitalism.

Another factor is just the educational system. Despite all the work that the Milton Friedmans and the Hayeks and the Miseses of the world – which is great work, great books, great arguments – all that effort still hasn’t made its way into the educational system where young minds are formed. I think too there’s certain factors of the way the human mind works against the proponents of capitalism and makes it more difficult for the pro-capitalist side to make its argument. The human mind is structured in such a way that we tend to favor the concrete over the distant, the specific over the vague. Whenever you make a case for capitalism you have to make arguments that are abstract, that tend to emphasize longer term benefits, things that are not immediately evident. That’s a problem that the opposite side, the side that the government is having a greater role in the economy, they don’t have that problem.

My favorite example is, let’s say you think there’s a problem with wages, that some people don’t make enough money. The free marketeer could tell you the story, well if you let wages be free eventually people will acquire skills, will have an incentive to do so, will invest in education or work harder to get promoted, and eventually they’ll get up the income scale. That’s sort of a more longer term view and it can be mentally grasped, but it’s a lot more clear and vivid if you could just tell people, or we could pass a law and we can set a minimum wage at x level where we think people are going to be less poor. And there’s the end of the story. There’s an easier story that the other side has to tell, and I think that plays into this situation with the millennials.

Transcript by: Annie Zhou <a2zhou@ryerson.ca>

LINK HERE to download the podcast

07/26/2017 - The Roundtable Insight – George Bragues On How The Financial Markets Are Influenced By Politics

07/26/2017 - The Roundtable Insight – George Bragues On How The Financial Markets Are Influenced By Politics