Charles Hugh Smith is an author, leading global finance blogger, and America’s philosopher we call him. The author of nine books on our economy and society including A Radically Beneficial World: Automation, Technology and Creating Jobs for All, Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change, and The Nearly Free University and the Emerging Economy. His blog, http://www.oftwominds.com has logged over 55 million page views, probably more by now, and is #7 on CNBC’s top finance sites.

Last time we talked about the commercial real estate bubble and we thought today we’d do a special focus on the millennial generation and how financial repression through repressed interest rates and quantitative easing has resulted in asset bubbles that ultimately have affected the millennial generation in terms of their values, how they look at the economy and life and the way they’re conducting themselves in the economy: what they’re facing in terms of the housing market and the job situation.

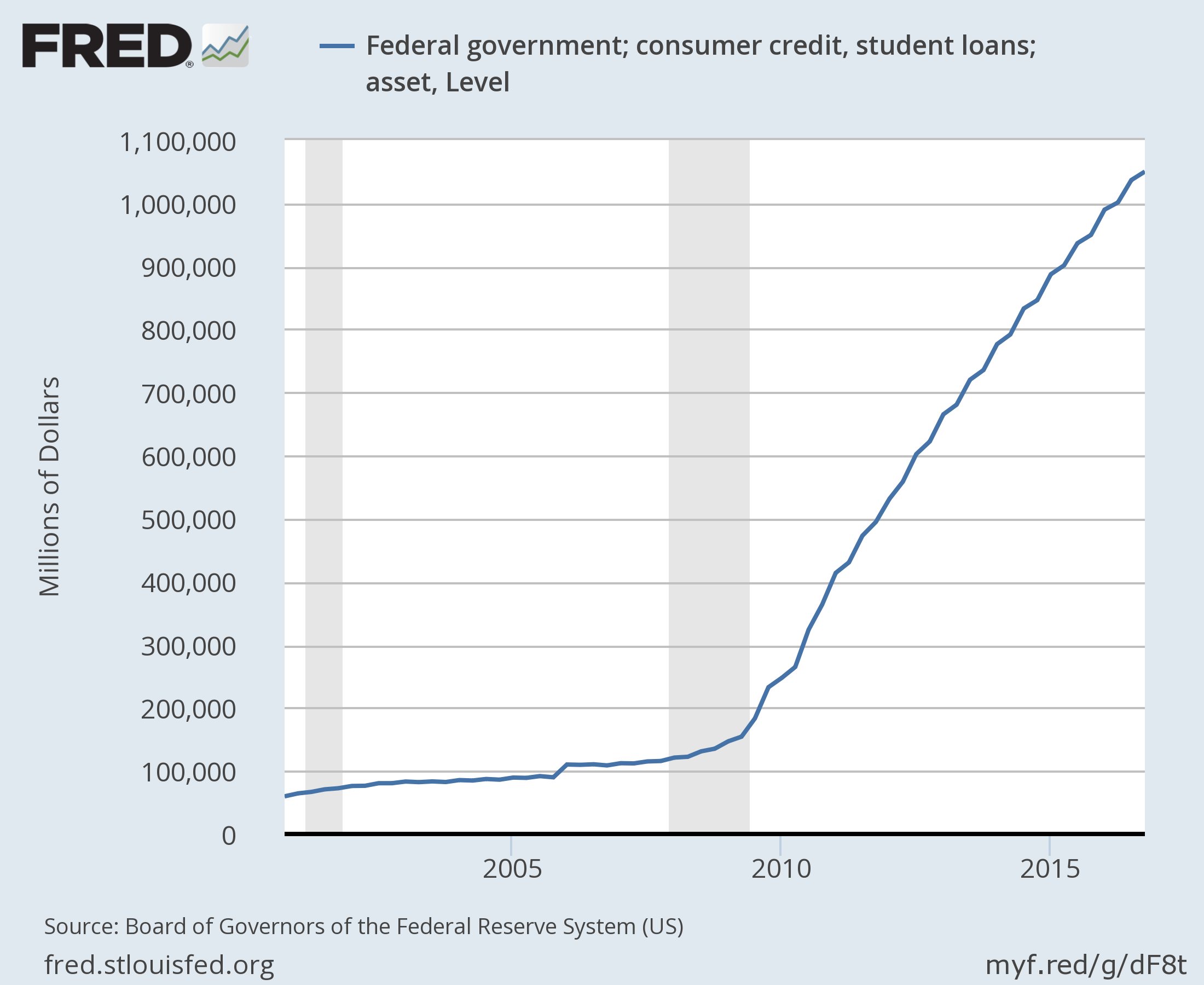

Many millennials are carrying student loan debt, nowadays a small student loan debt is $25,000-$30,000. If someone can escape with a bachelor’s diploma and only have $30,000 in debt, they’re considered to have done quite well. But in reality, that’s a pretty large debt for somebody who doesn’t even have a full-time job yet.

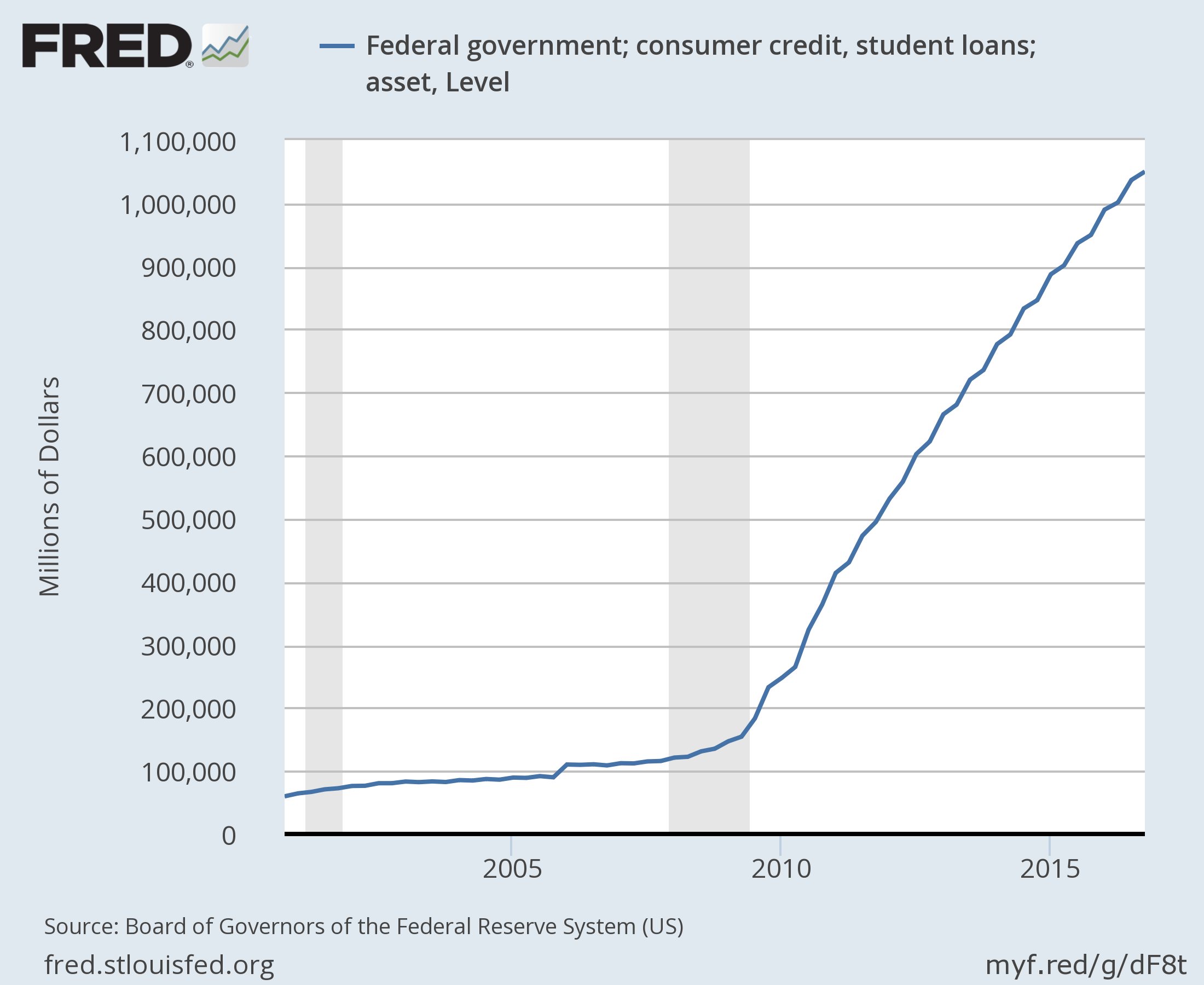

In cases where the central state guarantees any sort of lending and the lender can’t lose money because the government will step in and cover any losses, there’s a huge incentive to lend out to marginal borrowers and to really push every loan you can. And that’s exactly what we have with student loans: anybody that is breathing can get a student loan in an immense amount, and these are non-recourse loans right? Talk about financial repression, you can’t take them to bankruptcy court or reduce them in any way short of a few government programs. The interest rates on student loans are not that low, sometimes they’re as high as 7.5%-8.5%, so millennials have that burden on them right from the start.

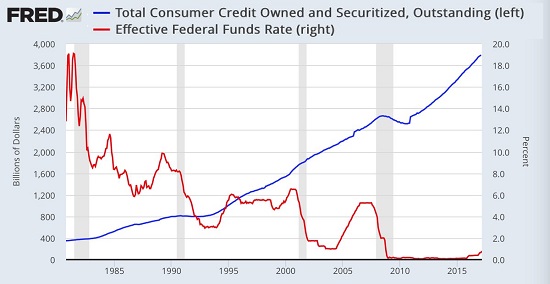

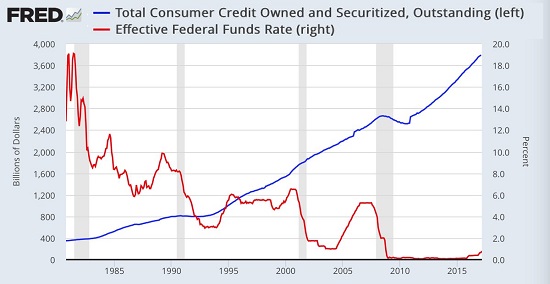

Many of the millennials grew up seeing their parents under a lot of financial stress mostly due to the bubble pop global financial meltdown in 2008-2009. So this has made them very wary of debt. And consumer debt still continues to climb. The total consumer credit owned and securitized chart shows a minor dip in the 2009 time frame, but has since rocketed even higher by another 1.2 trillion.

Marc Faber explores the concept that the millennial generation is much more risk adverse. We can see why, they’ve observed the damage and the stress and the losses that can result from taking on way too much debt and not having enough income or collateral to support it. So, they’re very cautious about taking on gigantic mortgages that their parents did and buying new cars and adding debt on top of debt on top of debt. And so as a generalization, they’re less willing to take the risk of taking on a gigantic mortgage, and I mean by that in the $700,000-$800,000 range, right? That risk aversion, it carries several potential consequences. One that was being discussed in the essay was that there’s less entrepreneurial activity for the same reason: why risk everything on a business that might fail?

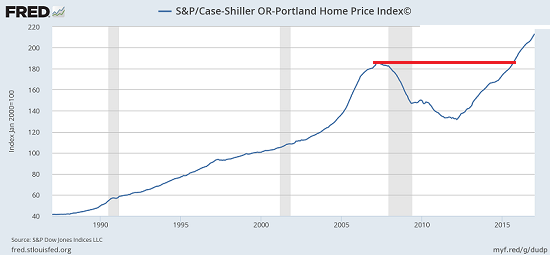

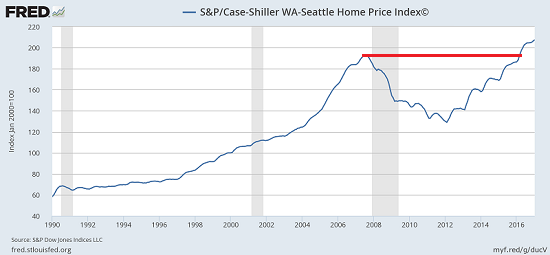

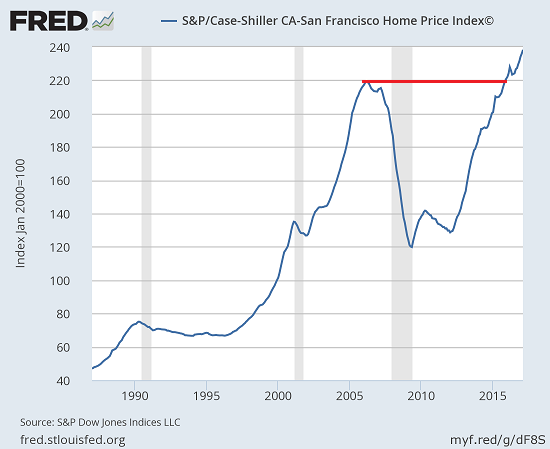

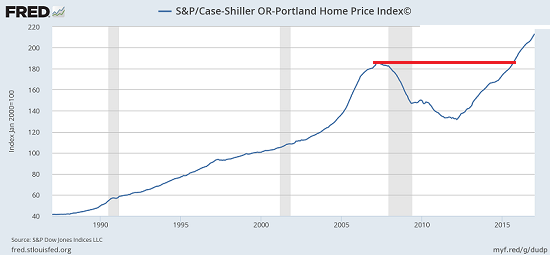

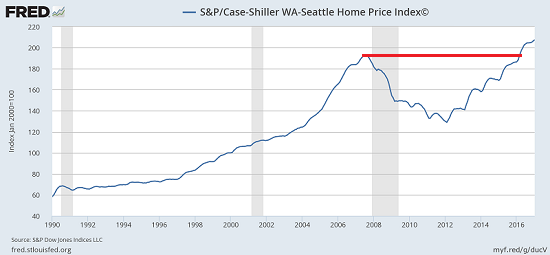

Seattle and Portland top the list of where students would like to move after college, based on various surveys. And according to the Case-Shiller home price index, these two cities now have exceeded the 2007 bubble in terms of housing valuation.

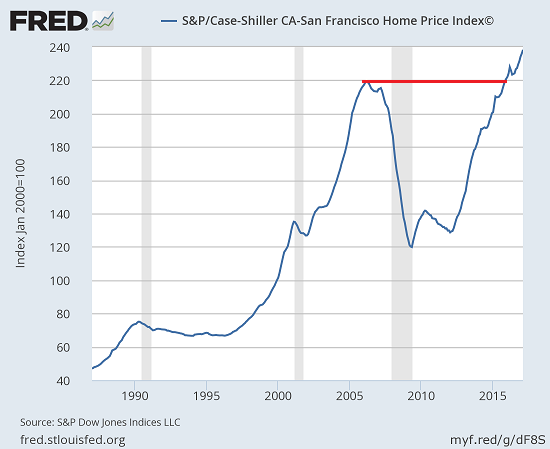

And many other favoured cities that are attractive to millennials like the San Francisco Bay area is also exhibiting this enormous home valuation bubbles or expansions. So then that raises the question, what are the millennials going to do? I don’t think there’s any evidence at this point to presume that the millennials are going to suddenly in some magical point in the future start making a lot more money and be able to afford overvalued housing. There’s no evidence for that, all the trends are the opposite: stagnating incomes and a millennial income trend that will stay sub-par, below that of previous incomes for decades to come.

Joel Kotkin, who studies demographics and the economy, thinks millennials do want to buy and own homes, but they’re only willing to do so if they can afford them. So the opportunities could lie within some of the smaller cities. For example, a house in Columbus Ohio, which is a classic college town in the upper Midwest can sell for less than $50,000.

It will also more difficult for the millennial generation to inherit their parents’ home, because the cost of retirement is so high, and most of their parents are forced to sell their homes instead of just giving it to their children. Housing is becoming increasingly expensive to build due to government fees and regulations on building in most cities, and government programs merely subsidize this process at a cost to the taxpayers; and rent control has been a disaster because that immediately kills off any new construction and reduces the incentive for land owners and landlords to maintain their property because their income is fixed.

Because of this, we’re seeing many innovative alternative housing solutions such as the tiny house movement and retro-fitting dying malls, using them used for housing instead. In addition, there’s an increasing trend of millennials moving towards smaller cities and working at home, telecommuting, and utilizing internet online based businesses. Because of this, local governments that are willing to accept innovations and ease building regulations are the ones who are more likely to prosper.

Summary by Jacob Dougherty jdougherty@Ryerson.ca

LINK HERE to download the MP3 Podcast

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Richard: Today we have Charles Hugh Smith. He’s an author, leading global finance blogger, and America’s philosopher we call him. The author of nine books on our economy and society including A Radically Beneficial World: Automation, Technology and Creating Jobs for All, Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change, and The Nearly Free University and the Emerging Economy. His blog, http://www.oftwominds.com has logged over 55 million page views, probably more by now, and is #7 on CNBC’s top finance sites. Welcome, Charles.

Charles: Thank you, Richard. That’s an introduction that’s going to be hard to live up to. I’m a beginner here, we’re just exploring interesting topics okay? I don’t have all the answers but we have some interesting topics.

Richard: Great insight as always, and last time we talked about the commercial real estate bubble and we thought today we’d do a special focus on the millennial generation and how financial repression through repressed interest rates and quantitative easing has resulted in asset bubbles that ultimately have affected the millennial generation in terms of their values, how they look at the economy and life and the way they’re conducting themselves in the economy: what they’re facing in terms of the housing market and the job situation.

Charles: Right, and you know Richard it’s hard to know where to start, but I think we could profitably start with the basic context of the economy and the millennial generation. And so in terms of financial repression, perhaps the one key sector that we need to look at is student loan debt because so many millennials are carrying student loan debt, and you know a small student loan debt is like $25,000-$30,000 if someone can escape with a bachelor’s diploma and only have $30,000 in debt they’re considered to have done quite well, but when you think about it that’s a pretty large debt for somebody who doesn’t even have a full-time job yet.

Richard: Yeah, mine was $13,000 I think when I came out, $13,500

Charles: Wow that was very low. And nowadays, 10 times that is not uncommon especially if you go to graduate school. And so we all know why this is but it’s worth touching on because the financial repression part is when the central state, you know the central government and its central bank, when the central state guarantees any sort of lending where a lender can’t lose money because the government will step in and cover any losses. Well, then there’s a huge incentive to lend out to marginal borrowers and to really push every loan you can. And that’s exactly what we have with student loans: anybody that is breathing can get a student loan in an immense amount, and these are non-recourse loans right? Talk about financial repression, you can’t take them to bankruptcy court or reduce them in any way short of a few government programs such as if you join the government service and then you get a reduction and so on. So it’s like the financial system on financial repression steroids. And so they’ve really tasted the worst of neoliberal banking, the interest rates on student loans are not that low, sometimes they’re as high as 7.5%-8.5%, and then the higher level education system, which is supposed to be concerned with educating the youth have just gorged on all this free money, built fabulous buildings on campus. And the administration, I just looked at this statistic, the number of administrators in higher administration in America went up 34 fold in like 30 years where the number of students barely rose, or that was much more modest. So anyways this is like the worst possible combination of financial repression and state guarantees, and so the millennials have that burden on them right from the start.

Richard: Yeah, just trying to get out of the gate in terms of leaving the nest or getting a family formation how can they do that? How can they buy a home or a car, just getting out, right? A lot of them have difficulty even getting a job even given the large amount of debt to begin with.

Charles: Right, right. And you sent me several interesting articles talking about the impact of the last decade’s financial stagnation on the millennial frame of mind or their value system. And of course, a lot of them grew up seeing their parents under a lot of financial stress, during the bubble pop global financial meltdown in 2008-2009. And so this has made them wary of debt and again just for context, consumer debt continues to climb, and this of course is mostly people who are older than their early twenties, it’s hard for them to acquire much more debt than their student loans. I have a chart here from the St. Louis Fed, and it’s the total consumer credit owned and securitized. And it shows a minor dip in the 2009 time frame, and then it’s rocketed even higher, it’s rocketed another 1.2 trillion.

So I think that the millennials are well aware that the entire system, not just the student loans that they’re under, but the entire system is incredibly burdened with debt.

Richard: And so how does this resulting in their views, their values, how they’ve grown up, and what they see as prospects for jobs, and just where to live in general, does it make sense to live in the inner city or out in the suburbs exurbs?

Charles: Right, right. Well one of the essays you sent me was an excerpt from Marc Faber’s recent essay kind of exploring the concept that the millennial generation is much more risk adverse and we can see why, because they’ve seen the damage and the stress and the losses that can result from taking on way too much debt and not having enough income or collateral to support that debt. So, they’re obviously wary of taking on these gigantic mortgages that their parents did and buying new cars and adding debt on top of debt on top of debt. And so I think as a generalization, they’re less willing to take the risk of taking on a gigantic mortgage, and I mean by that in the $700,000-$800,000 range, right? You and I were speaking, a one million dollar house in Toronto or Vancouver or Seattle or the San Francisco bay area or Boston; you know you name it, I mean a million bucks you have to put down a quarter million, and so you’re on the hook for $750,000 that’s a lot of money. And so that risk aversion, it carries several potential consequences. One that was being discussed in the essay was that there’s less entrepreneurial activity for the same reason: why risk everything on a business that might fail?

Richard: Yeah, I mean the millennial generation is the least entrepreneurial.

Charles: Right, and that’s at odds with this sort of tech hub environment in which the assumption is here’s a bunch of 23-year-olds or 25-year-olds starting a billion dollar company in the living room. But that’s actually just the bleeding edge of a generation that’s generally risk adverse. So then we go look at housing, and I submitted a couple of charts that showed two of the millennials favourite cities at least judging by surveys of where you’d like to move after college, Seattle and Portland are quite high on that list. And according to the Case-Shiller home price index, those two cities now have exceeded the 2007 bubble in terms of housing valuation.

And I think that many other favoured cities, cities that are attractive to millennials like Austin Texas and San Francisco Bay area, I mean there’s a lot of other places that are exhibiting the same kind of enormous home valuation bubbles or expansions to the point that only the top earners can afford that, and so then that raises the question, what are the millennials going to do?

And so Joel Kotkin who’s a demographer, you know studies demographics and the economy, his view is millennials do want to buy and own homes, but they’re only willing to do so if they can afford them. And so that basically eliminates most of the super desirable core city centers of Seattle, Portland, Austin, San Francisco and so on, and Boston, Brooklyn, Manhattan you know. And so where do they go to buy a home? And his theory, he proposed that they are willing to move to the suburbs if that’s where it’s affordable. But my question on that is, I don’t think that suburban homes in super desirable urban areas like greater Seattle and around Austin, around the San Francisco Bay area, those houses are not much cheaper than the core houses, so I’m sure that that’s really an opportunity. So I kind of think that the opportunities at least in North America are in smaller cities. In the range of 50,000-100,000, maybe a quarter million residents, not these megalopoleis. And the only millennial I know, well I know a few millennials that have purchased homes, one bought a house in Portland for I think it was around $400,000 or $450,000. And they both work and they had a condo that had purchased a while ago so they had some equity. And then another couple bought a house in Columbus Ohio, which is a classic college town in the Midwest, the upper Midwest for less than $50,000. Now this was not a large house, and it was an old house, and you know it needed some work and all that. But I mean we’re talking about a house for less than 50,000 roughly a tenth of the values of these hot desirable core cities. So that raises some interesting investment questions about where the millennials going to go and where is real estate going to be desirable to them.

Richard: Yeah and it also factors into who are the baby boomers going to sell to, because if there’s nobody there or no demand to buy these houses due to lack of income or insufficient income, that could also pose some challenges to baby boomers looking to sell their house nest egg.

Charles: Right, I think that’s a huge demographic question that I haven’t seen any really good statistics on because of course most of the boomers are still in their late 50s or 60s, early 70s and they’re not yet to the point where the older generation like the boomer parents, the so-called silent generation, which has sold their houses or given them to their offspring, their adult children. But we’re talking about such huge numbers, and just for context, in general roughly two-thirds of the baby boom generation owns homes, about 65%, low 60s. So there’s a large percentage of the boomers who own homes, and typically they bought these homes when they were younger and had families and so there’s going to be a huge incentive for them as they age to unload these houses. And in the good old days when there was more family wealth, they might have been able to afford to basically give that house to their children, and then retire somewhere else on their income. But now, with the cost of retirement so high, and I know because I’m 63 and my mom is in a retirement home so I know if you can get into $4,000 or $5,000 a month on assisted living that’s usually quite reasonable and it can go as high as $7,000 $8,000 $9,000 a month. So almost everybody facing that kind of sum of money is going to have to sell their house in order to liquidate their equity in order to retire on that. So they’re not going to be able just to hand the keys over to their adult children. So that’s a question that I don’t think we know the answer to, but if millennials can’t buy the boomers house at the current value than basic supply and demand economics suggests that prices will have to fall to the point at which they’re affordable to millennials. Which in many areas suggests a 50% drop, right.

Richard: Yeah, yeah exactly. I mean they may be initially thinking perhaps I’ll just get the house through inheritance and therefore I can focus my current income on things like coffee at Starbucks and looking for trips to Machu Picchu or something, you know Patagonia. This is where their values and emphasis seem to be. So they might be saying let me just spend that money there and then I’ll eventually get the house. But the house is now likely going to be needed for retirement by the baby boomers, is what you’re saying.

Charles: Right, and so they won’t be able to inherit. The parents are going to be selling that house in order to extract the equity to retire on or downsize. In which case they’ll be competing with their children for affordable housing, small apartments and that kind of thing. So the other key element here is what can we expect in the future for millennial incomes? And every indication that we have currently, statistically, is that millennials are making considerably less money at the same age compared to the gen X and boomers made in their early to mid-20s and early 30s. And what we do see is a great concentration, a skewing of national income to the top 1% and 5%. I mean this is well established that the top 5% what we might call the techno-crack professional entrepreneurial class, is their income is continuing to grow ahead of inflation and expenses, but everybody else below that, their income is stagnating. I don’t think there’s any evidence at this point to presume that the millennials are going to suddenly in some magical point in the future start making a lot more money and be able to afford overvalued housing. There’s no evidence for that, all the trends are the opposite: stagnating incomes and a millennial income trend that will stay sub-par, below that of previous incomes for decades to come. So I don’t think there’s any magic bullet on that, and if we look at what’s the other magic bullet in financial repression armory, well it’s lowering interest rates to zero. Hey, we’ve been there for 8 years, right. Or near zero, and mortgage rates below 4% were basically unprecedented lows and they’re starting to click back up above 4, 4.5. So we’ve already used up all that ammunition about lowering interest rates to near zero, to push mortgages down to make very overvalued homes affordable, that’s done. In fact, the trend suggests we’re at a bottom there and mortgage rates may continue to click higher and put another sort of pressure on the incomes of millennials.

Richard: Yeah, so the repressed interest rates is sort of affecting a large number of age groups because the inability to get sufficient income off of fixed income assets and investments as baby boomers retire, looking maybe more to go into bonds or fixed income type of investments, with the interest rates being so low, that’s very difficult. And therefore maybe you go to the house and reverse mortgage and all that. But at the same time that’s all secondarily affecting the millennial generation as well so there’s not much discussion in that regard, you know how repressed interest rates have negatively affected the millennial generation.

Charles: That’s right, that’s right. If you’re a borrower, if you’re a saver then of course you’re receiving very little income. And that’s hurt the older generations which have been saving money for their retirement.

But the millennials who are the borrowers of student loans and auto loans and so on, other than the teaser rates that have been offered for auto loans, if you’re paying a student loan or a credit card, I mean the interest rates are sky high still, they’re very high. As we know credit cards are often 15%-16%. And so the millennials aren’t really getting an enormous benefit from this so-called zero rates because much of their debt is not at 1%. Yeah, you can get a 1% auto loan if you qualify, but most of the debt out there is at much high rates.

Richard: Yeah, exactly.

Charles: So, Richard maybe one of the key questions here going forward is, what happens to the United States, and perhaps we can include Canada with at least the high value cities of Toronto and Vancouver where young people that just have regular normal income jobs are priced out of buying a single family homes in those areas. What happens to the society and the economy when people can’t afford to buy a home, that they’re just renters? I mean what impact does that have socially, economically, and politically? I don’t think we’ve really explored that too much. And what Joel Kotkin was arguing against was the idea that oh the millennials will be perfectly happy to be renters their whole lives. And he was suggesting that well maybe that’s just a happy story without any actual basis, maybe they’ll be quite angry that they can’t afford to buy a house.

Richard: Yeah and just the sense of ownership that goes along with that, I mean there’s some other points that go to that regard in that Marc Faber article where he references a number of authors, so that we talked before about the risk aversion that’s infecting even now corporate America in terms of in the old days there was budgets for doing research and development. And now it’s being more money is spent on legal compliance and human resources instead and less on training less on research and development. That’s also related to the fall in entrepreneurial activity, innovation. And then Marc quotes Edward Gibbon in terms of how it ended up like in Athens in Greece in the ancient history where in the end more than they wanted freedom, they wanted security when the Athenians finally wanted not to give to society, but for society to give to them, when the freedom they wished for was freedom from responsibility, then Athens ceased to be free. And so that is a big issue in terms of what could happen resulting from the spirit of risk aversion and a sense of greater entitlement from the government.

Charles: Yes, that’s an excellent point, Richard. And kind of following that up, Joel Kotkin also mentioned that there’s a generational conflict brewing in land use and how we provide housing how we build housing. And as we all know that the last I’d say 20 some years has been dominated by nimbyism, like not in my backyard right. Don’t build any new housing, don’t build any high-density housing, don’t build a new complex by my house, right. And so that has really stifled construction in a lot of cities, especially those with very little open land left. And then, of course, the local governments have raised the fees on building, and so it can cost I think the number that he mentioned was $50,000 per unit just for the development costs, you know the permits and sewer connection, and you know there’s a $10,000 fee for everything right. For each item, and so if it costs 50,000 just to get a permit basically before you’ve even spent a dollar on the land, and then the whole process is dragged down so you spend two years basically paying interest and principal on the land you purchase before you actually get permission to build. All these things have made it so the housing that is built is super unaffordable. And so if we’re going to look at the millennial sort of tendency some people say towards socialism, like well the government is the entity that can fix this, if we look at what the government has done with housing, for instance rent control has been a disaster because that immediately kills off any new construction and reduces the incentive for land owners and landlords to maintain their property because their income is fixed. And the other thing that the government has done in response to this affordable housing crisis is it’s built so-called affordable housing, but the vast majority of cases that is merely subsidizing housing. In other words, it still costs $250,000 to build that tiny apartment per unit. And then the taxpayers subsidize $150,000 of it, making it affordable. But that’s only a subsidy, they didn’t do anything to lower the cost of construction or ownership. And so obviously there’s extreme limits on that kind of thing. And so many cities end up patting themselves on the back for building like 400 units because this subsidy cost is so extreme. And so maybe what the millennials could do, and I don’t know if there’s any potential for this, but if they took a political voice, they might do better than instead that government builds subsidize housing that just adds burden to the taxpayers, maybe they can overturn a lot of these super restrictive codes and nimbyism, you know that’s choking the construction of new affordable housing.

Richard: Yeah I think the regulation issue is big, and it’s also affecting if you look at the positive side of some of what’s happening, like this move towards tiny houses where you have maybe 160-1,000 square feet type, very small houses that can be almost like mobile homes. And then maybe the retro-fitting also of dying malls to have them go into housing, to housing developments to be retro-fitted from malls and just other things like containers that are being retro-fitted into houses as well, all of that. But there’s a lot of regulations in many communities that prohibit that type of thing to happen in terms of putting these tiny houses on property.

Charles: That’s right, there has to be a change in as you say the regulatory spirit of the law, and that’s a political process. But you know, Richard, to speak briefly in an investment potential here, where is there an opportunity here for people that want to participate in this huge demographic economic housing shift we’re talking about. Well, just anecdotally, I can’t give you national statistics, but just from people I talk to, it seems like the opportunity is in these small cities that have some assets. In other words, they have a port, you know they’re on the seacoast or they have a riverfront or they have some state universities, these kinds of assets that tend to be institutional or profoundly economic. Those small cities seem to be where the millennials can afford and where they’re interested in revitalizing. I was speaking with another blogger podcaster, and he was saying Buffalo New York, which was for quite a few years considered a poster child for urban decay upstate New York. And he said it’s actually becoming a happening place because young people are moving there and opening brewpubs because it’s cheap. And so I think the key here is to find places where housing and commercial space to open a restaurant of café or some sort of business, if you can find a place with super cheap rent super cheap housing you can buy for like I said in a neighborhood of $40,000 $50,000 $60,000 $70,000 $80,000 than that’s going to be a magnet for young people for the affordability and as we all know the trend for many decades has been the artist and creative types will go to a rundown neighborhood or town and then they will revitalize it because it’s affordable to them. And so that may be the opportunity going forward, is in smaller cities that have some assets, and by that I mean compared to a place that was dependent on one auto assembly plant, and so when the plant closes the whole place is shut down and there’s no other assets to draw on. But if you have institutions then there’s some foundation there that can support a revitalization and so just people have told me Buffalo New York seems to have some magnet potential and Columbus Ohio is two examples and I’m sure there’s many others, dozens. And so if I were a real estate investor I would start looking at places like that.

Richard: Yeah, no I think you’re right. And that’s also consistent with the trend towards a move to the center, the so called fly over America land between the coasts in the interior in the Midwest where there was places that have been very depressed, Buffalo, maybe Detroit. Very very low cost and the cost base is already beginning from a very low point. But at the same time you’ve got resources, you’ve got land, arable land for agriculture potential. And then the potential for fiscal spending on infrastructure, so you’ve got the Midwest that has the potential there, where it’s traditionally played a role. So that sort of whole manufacturing infrastructure agriculture in the interior of the U.S. that trend. And certainly, people moving out of California for various reasons in high-cost areas, highly taxed areas, going more towards the favourable areas in the interior.

Charles: Yes, absolutely, and you mentioned agriculture and arable land, well I also just, I don’t know them personally but through other millennials I know it turns out there’s quite a few millennials who are homesteady. In other words, they’re buying abandoned farms or they’re buying rural land and starting to raise pigs and chickens. And again, the cost is so much lower, and I want to make a last point here which is this could be a global trend. In other words, it may not be isolated to the U.S. or North America. Because I know, again anecdotally, that there’s evidence of this in Japan. Which is highly urbanized, highly expensive, you know basically housing is not affordable in Kanto plain around Tokyo. That there’s millennials there who are just giving up their full-time job, moving to these abandoned villages, or almost abandoned, there’s only a few old people left, and they’re renting these beautiful old farm homes for like 200 bucks a month including the land around it, starting a garden, and then they’re working part time online. Because a lot of them they’re illustrators or they’re graphic designers, or they’re programmers. And so that’s that other aspect of our economy, what I call the emerging economy or what a lot of people call the fourth industrial revolution, the digital economy for a lot of young people with technical skills, they can work anywhere. So they can actually afford to live in a small town that’s super cheap and just work part time online. So there’s a lot of positive things that the government can’t destroy here with over regulation. And there may be ways to get around the damage of the financial repression. And so anyways, those are the potential positives.

Richard: Yep, exactly ending on a positive note that through some type of regulatory reform process as we discussed earlier together with innovative ideas on housing in terms of tiny houses, container housing, retrofitted malls, with the trend of working at home, telecommuting, internet online based businesses, the whole retail sector, malls dying but everybody setting up businesses that are online through Amazon or Shopify. Maybe that’s the positive trend to allow more affordable housing and opportunities.

Charles: That’s right, that’s a good summary Richard because if it’s not affordable it’s not going to work for the millennials. They’re not interested in overextending themselves on debt. And so it has to be affordable and that’s where the opportunity is for everybody who wants to be part of this, I think is to provide affordable retail space and affordable housing and get in on that as you say with things like tiny homes. And maybe my final comment would be, the local governments, the local city governments, and the county governments who get in on this are going to prosper. The ones who allow tiny homes and make it easy for young people to start businesses, low-cost low fees, they’re going to prosper. And everybody who is in this high regulatory barrier, high cost, high expenses, overregulation, they’re going to die. And we already see that, and I’d say Chicago is probably a good prospect for a city on the way down from just too many expenses and overregulation. So, yeah.

Richard: Well, that’s great insight Charles, and how can our listeners learn more about your work?

Charles: Yeah, please visit me at oftwominds.com (http://www.oftwominds.com)

Richard: Great, and we’ll do another session on another topic in about a month.

Charles: Yes, looking forward to it.

Richard: Great, thank you very much, Charles.

05/16/2017 - The Roundtable Insight: Charles Hugh Smith On How Financial Repression Is Affecting Millennial Generation Values

05/16/2017 - The Roundtable Insight: Charles Hugh Smith On How Financial Repression Is Affecting Millennial Generation Values