LINK HERE to download the MP3 PODCAST

SUMMARY – also see FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

Today we have five panelists from around the world, Russ Lamberti from Cape Town, South Africa, Mark Valek from Liechtenstein, Chris Casey from Chicago, Bill Laggner from Dallas, and Mark Whitmore from Seattle.

Chris is the Managing Director of WindRock Wealth Management. He combines a degree in Economics from the University of Illinois with a specialty in the Austrian school of Economics. He advises clients on their investment portfolios in today’s world of significant economics and financial intervention. He’s Also written a number of publications on a number of publications on websites including the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Zero Hedge, Family Business, Casey Research, and Laissez Faire Books. He is a board member of the Economics Development Council with the University of Illinois, a Policy Advisor for The Heartland Institute’s Center on Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate.

Bill is a Co-founder of Bearing Asset Management, he’s a partner with Kevin Duffy that manage the Bearing fund using an Austrian School of Economics lenses in terms of identifying boom-bust cycles, value in the marketplace, bubbles, and distortions created by both fiscal and monetary authorities. He’s a graduate at University of Florida, began his investment industry career in the late 1980s initially as a stockbroker, and then moved to the buy side at fidelity investments. He’s been featured also in Barrons, Reuters, and CFA magazine.

Russ Lamberti is the founder and chief strategist of ETM Macro Advisors. Which provides Macroeconomic intelligence and strategy services to asset managers, family offices, and high net worth individuals. He is the Co-Author of “When Money Destroys Nations”, a book about Zimbabwe’s hyper-inflation, and he’s a contributing author at the mises.org institute.

Mark Valek is a partner investment manager of incrementum, he’s a Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA) and has studied business administration and finance at the Vienna University of Economics. From 1999 he worked at Raiffeisen Zentralbank (RZB) as an intern in the Equity Trading division and at the private banking unit of Merrill Lynch in Vienna and Frankfurt. In 2002, he joined Raiffeisen Capital Management and in 2014 he published a book on Austrian Investing. He’s one of the authors of “Austrian School for investors”.

Mark Whitmore is the Principal, Chief Executive Officer of Whitmore Capital. Mark has been managing personal portfolio assets, periodically publishing newsletters and blogs, and providing pro bono financial planning/investment consulting since leaving law in 2002. His specialties are currencies and international economic analysis. He obtained a B.A. in Political Studies from Gordon College, graduated Summa Cum Laude at the University of Washington he earned a Masters of International Studies (MAIS) at the Jackson School and a J.D. from the School of Law.

Austrian School of Economics Explained:

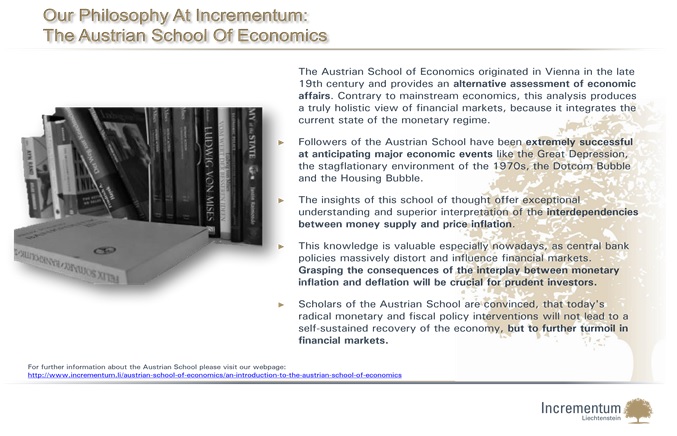

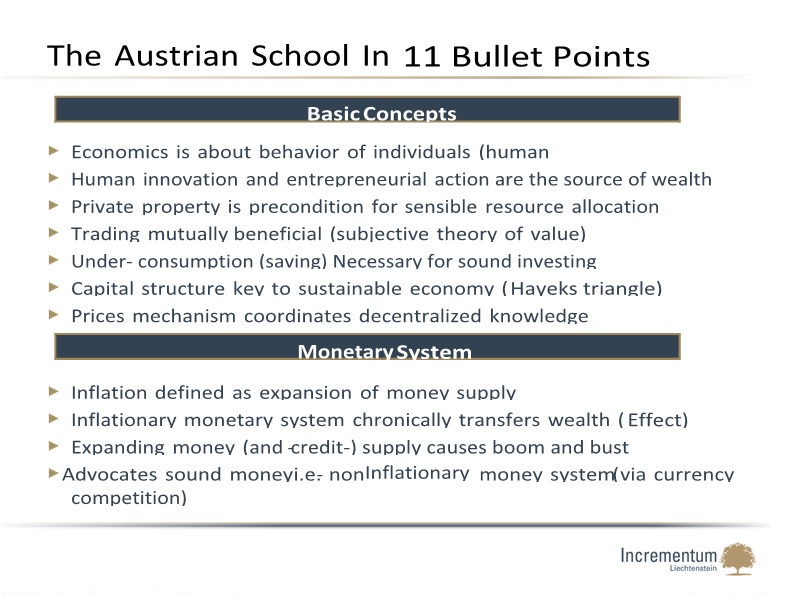

Mark Valek defines some basic points and differences of the Austrian School as: Economics about the behavior of individuals and human action, The Subjective value theory, under consumption of savings is necessary for sound investing and growth, capital structure being key to a sustainable economy, and price mechanic mechanism coordinates the centralized knowledge. Perhaps the most important distinction of Austrian Economics is its view towards the monetary system. Some of these points are inflation being defined as expansion of the money supply and finally expanding money and credit supply causes a boom and bust cycle in the business cycle theory.

He points out that these are the typical differentiating points, but this is by no means a complete list, and you can discuss the differences between the Austrian School and traditional Keynesian theory.

Russell Lamberti thinks that one of the key differentiators from a practical analytical and investment perspective was that the Austrian school draws a very straight and consistent line between microeconomics and macroeconomics. He notes that at the microeconomics level, Keynesianism is very similar, but when they aggregate it up to the macro, a whole different theoretical framework is used and there’s essentially no consistency between neo-classical and Keynesian micro and macroeconomics so there’s a fundamental break down there. He ends the thought by saying in today’s Macro world it’s only really the Austrians who are talking about the unsustainability of certain demand trends because of misallocated capital and misallocated productive resources and that’s why he thinks the Austrian Business Cycle is such a key distinguishing feature of the Austrian school.

Chris Casey discusses why Austrian Economics can provide new insight, saying that Austrian Economics is the only one that really puts man at the center of the discussion. It boils economics down to man in the context of nature as it relates to scarcity for his needs and wants. And in so doing they then use a number of first principles that build on from the deductive reasoning standpoint to create a consistent and sound economic school and economic philosophy. And that’s what really makes the difference from the other economic schools out there. It’s not just the conclusions, it’s how we arrive at those conclusions.

Mark Whitmore adds that specifically, the role of central banking is something that is really distinct from an Austrian perspective vs Keynesianism. Specifically the asset price inflation that you’ve seen has largely been ignored by Keynesians in the last two bubbles. Now we’re into a third bubble I would argue as well. And essentially the Fed and the Keynesians will continue to point to there being really no headline inflation pressure and hence there’s really no reason to begin to normalize or adjust or move up interest rates meaningfully. And I think that from an Austrian standpoint, this exacerbates this boom-bust cycle which we’ve seen which has been really compressed in terms of time lately versus what has historically been the case. Since the mid to late 90s the amplitude of bubbles to the upside has just been far greater. He highlights Henry Hazlitt’s two points as far as critiques of Keynesianism. The first one being that fundamental flaw in terms of interest, with Keynesians tending to service the visible minority at the cost of the invisible majority and again it gets to this whole issue of government being the problem solver, the one that can allocate assets essentially, in its view, the most effectively from a Keynesian perspective in a counter-cyclical effective way, where the Austrians are much more skeptical of the accuracy of that. And second,the propensity under Keynesian Economics to over-consume in the present generation at a cost of creating massive debt or future debt for future generations to essentially somehow deal with, we’re sort of seeing that today in all developed parts of the world.

How it’s used in past, present and future Economies including how and why the 2007-2008 financial crisis happened:

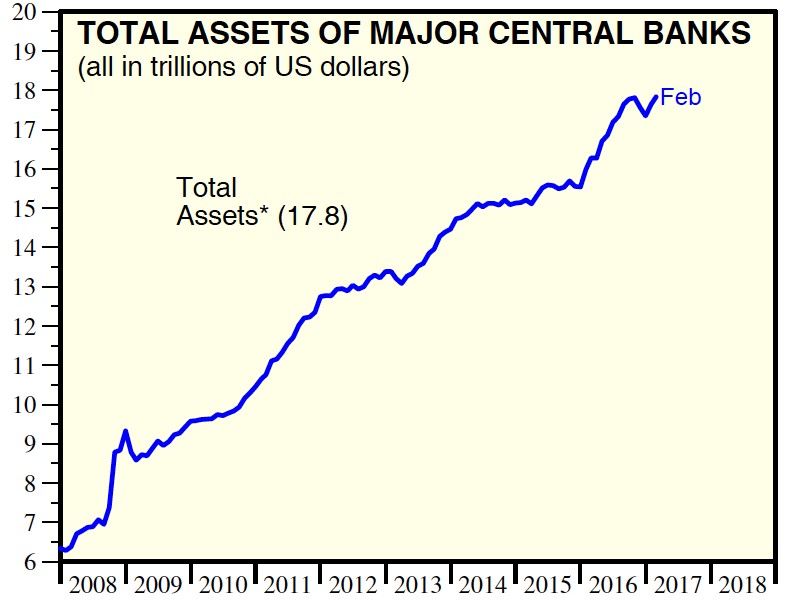

Bill Laggner says what was interesting was that the internet created this initial innovation wave decentralization wave, and of course due to excess credit creation, money creation, you had a bubble and then a subsequent bust. And then instead of letting the system purge and heal, the central banks led by the U.S. came and lowered interest rates and you segued from a technology bubble to a private sector credit bubble. And of course it went longer then everyone on this call thought it would, and it eventually hit a wall and again tried to cleanse and it’s interesting central banks let certain groups fail and then when things started to get out of hand, they stepped in and bailed out a number of politically connected contingents and then laid the foundation for this third bubble, and this third bubble’s gone on longer I ever imagined or my business partner imagined that it could. He also points out that the distortions are epic, and that this won’t end well.

Mark Whitmore chimes in discussing Kurt Rickenbacker’s idea of “Ponzi finance” which is a powerful analytical insight that essentially the boom-bust cycle is endogenous to the particular type of finance credit system you have in place.Credit can thus becomes increasingly untethered to any kind of historic connectors such as sound collateral. One increasingly witnessed these signs of the economy going off the rails in the upward direction in a trajectory that was simply unsustainable. So indeed that bubble went longer than most of us expected, and this one is truly epic.

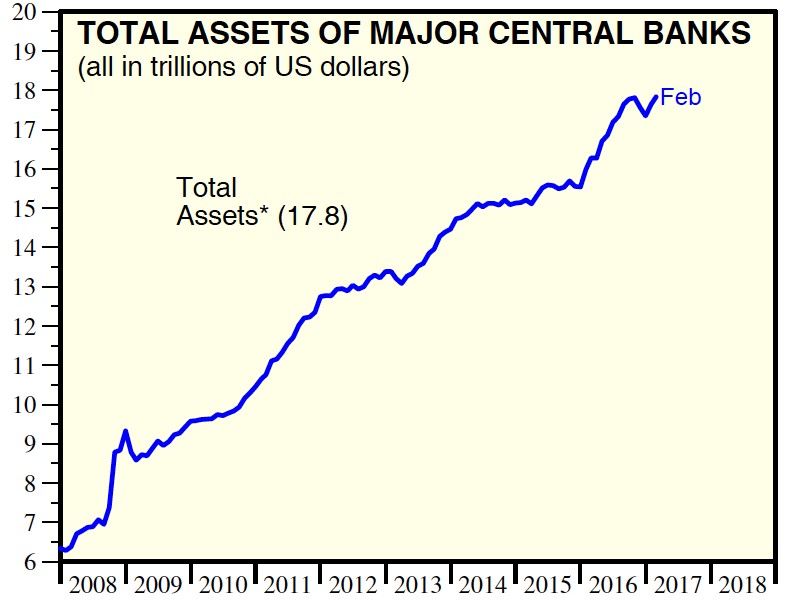

* Includes the US, ECB, BOJ and PBoC.

Sources: Yardeni Research, Inc. (www.yardeni.com); Haver Analytics

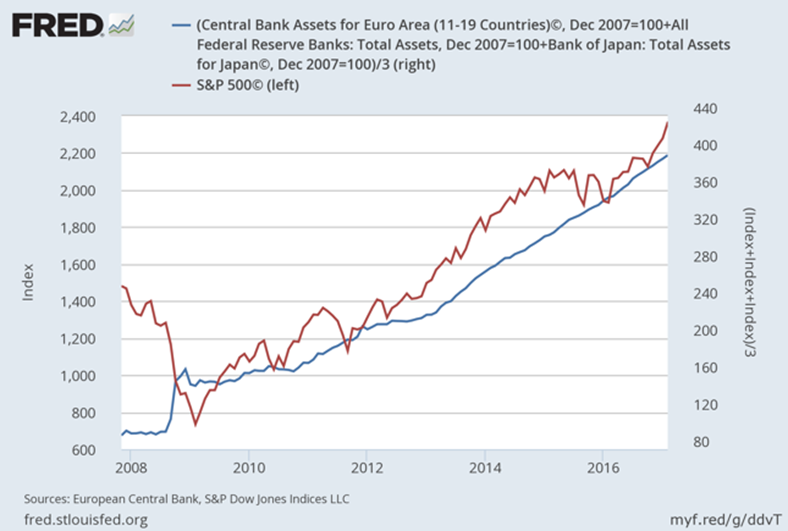

He notes that the curve and amplitude of the line showing the increase in central bank assets seen above is almost exactly the same as the line showing the increase in the S&P 500. He calls this the engine that’s driving what’s been taking place in terms of asset price inflation and ends by calling it highly unstable, and saying again that this will not end well.

Russell Lamberti emphasizes the importance in looking at this as three very big bubbles in a row, but also to think about the compounding effects of repeated malinvestment that has been essentially dis-allowed from correcting and from reallocating promptly. He also discusses this unwritten law against recessions, saying this is not just a problem in America, this is a problem everywhere in the world. Politicians don’t like recessions. As they push back through repeated cycles we have chronic malinvestment, chronic poorly allocated capital. And this creates a hostile working lifetime of living in an essentially very strange unreal financial and capital structure. He ends by saying: we’re in a third very excessive state of distortion and the best case scenario that we can hope for is a sharp, painful clear out of chronic malinvestment. That is the fastest path to genuine economic progress again, I hope we get there soon.

Chris Casey adds that when discussing how Austrian Economics explains the 08 crisis gives us some guidance to future bubbles in economic recessions, it’s worth recounting what can not explain the 08 crisis, and that is mainstream economics. And it’s worth remembering that in 2002 at Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday party that Ben Bernanke stood up and literally apologized for the great depression, and he basically said something to the effect of “we won’t do it again” and so that tells you central bankers pretty much around the world do not understand the causes of recessions at its most fundamental level. “They can’t explain why it occurs, they can’t explain why it’s a cycle, they can’t explain what Austrians call ‘the cluster of error’, why all these businesses have made horrendous investment decisions. They can’t explain why every recession is proceeded by monetary inflation, they can’t explain why certain industries are far more cyclical than say consumables. So it’s just something that cannot be explained, the Austrians do, and for the listeners who may not be all that knowledgeable on the Austrian School, in short, whenever you inflate the money supply, you are decreasing interest rates which distorts the whole structure of production, it forces economic actors to make investments they would not have otherwise done, that they would have otherwise deemed unprofitable, and it creates this malinvestment in the system, as my colleagues here today mentioned, we’ve already seen this play out twice in the last 20 years. And the response, if that’s the causation of a recession, the response should be hands off.”

The Austrian School Investing, Investments/Asset Classes/Investment Strategies

Bill Laggner discusses how knowing the Austrian business cycle theory is helpful in fact, during the second bubble, the credit bubble, he wrote an article with a colleague called “collateral damage”. And what he found fascinating about writing the article was the Bearing Credit bubble index created back in 2004 when it was pretty obvious that we were segueing into this new bubble. He says: I kept looking at the types of asset backed securities are being created mainly, and mortgage arena, and then the derivatives wrapped around it, and then attended a few conferences. But I started focusing on the collateral because it’s a confidence game, right, I mean people have confidence when these troubles start, they grow and what was interesting was in 2005 the home-builders had started declining severely and writing down land values ext. but subsequent to that you had maybe 12-18 months of watching paint dry. I mean the other related industries kind of kept chugging along. And it wasn’t until early 07 where the secondary market for certain types of mortgage backed securities just locked up. And that was the beginning of the end. So to me, when I look at excess credit creation through the socialization of credit by the central bank and or other government agencies like Fanny and Freddie in the U.S. I was looking at collateral that was kind of a helpful sign that we were near some kind of inflection point. I think what makes this cycle so much more difficult, and look full disclosure I mean we’ve had a net equity short bias for the last several years, and it’s been pretty painful. I think this cycle, because they’re all playing the same game, they’re all in together. Is there any limit to what the central bank balance sheets can go to? I mean, how many bonds can the central bank give Japan or the ECB or the Fed purchase, and I think it’s pretty clear that since all the chips are in the middle of the table, they’re going to continue to buy bonds, and try and hold certain parts of the yield curve suppressed to keep the game going.

Chris Casey discusses how it’s unclear if Austrian Economic principles are necessarily applicable to investing, but Austrian Economic conclusions certainly are. He goes on to say “They certainly are as they relate to the macroeconomic phenomena of recessions and inflation. Because these are the two forces that create the greatest risk factors regarding ones investment portfolios. The recessions are going to pop any bubbles that are out there pushing the equity markets, and inflation will destroy the bond markets. And when you’re looking at equities or bonds, these obviously make up for most people the vast majority of their investment portfolio or at least the core of the investment portfolio. So if you’re able to use Austrian economics to navigate these two risk factors, I think it presents a tremendous advantage for investing. As far as whether or not there’s been empirical evidence demonstrating this, not to my knowledge, I think it would be difficult to construct such a study for a couple reasons. One being the time period that we’re looking at. Austrian economics hasn’t been utilized in this form for very long. And secondly would be the sheer number of people using Austrian Economics in this fashion. It’s a very limited set. The people here on the call know that they represent a good portion of that universe, may be the universe, of people managing money with Austrian Economic concepts in mind.”

Mark Whitmore also tends to be somewhat skeptical as far as can you look at Austrian Economics as instrumental tools for specific kinds of investment analysis or recommendation. What he think is incredibly valuable is how you explain the efficient market theory; this idea that whatever the price of the given asset is at any time, it’s the “right price”. Because all the information is being priced in so trying to outguess the market is kind of a fool’s errand. And I think that one of the most basic, the most essential insight of Austrian Economics is this idea of subjectivism, and that prices are wholly derived by human beings, and one of the other schools of economic thinking that I think dovetails nicely with the Austrian school is Economic behaviorism, this idea that individuals are driven by greed and fear, and as a result, and this feeds very much into the boom bust cycle of the Austrian framework, that you get these ridiculous, unexplainable run-ups in asset prices that leads to catastrophic losses.

Russell Lamberti thinks it’s about creating a coherent perspective of macro-reality, saying how there’s so many investment firms, you go on their websites and they talk about how they like to find miss-priced assets because they believe that the market doesn’t always effectively price assets. But they’ve never really got a coherent reason why. He goes on to say “I think the nature of clusters of error of boom and bust cycles, of the business cycle creates a very coherent reason why you get big distortions and big mispricing. And what I try to do for my clients is I say to them that ultimately using Austrian principals is essentially about creating a coherent perspective of reality, and also using that coherent perspective of reality to compare it to the market narratives that emerge. Donald Trump gets elected, and there’s a narrative there that emerges, a reflationary narrative. A narrative might be that he’s going to deregulate and the market finds an excuse to run even higher. And you’ve got to kind of test all these market narratives against really sound perspectives of reality. In addition to that I’d say a few things: one is that an Austrian perspective gives you an understanding that you’re not in a free, unfettered market, you’re in a market where the state plays an incredibly dominant role and is essentially trying to plunder private resources. And so a huge element of investment strategy from an Austrian perspective has to be at the sense of you are defending your wealth against the plunderers”.

Mark Valek thinks knowing Austrian Economics provides you with a potentially huge edge. He points out that even though you can read about it online at mises.org or on other websites, many people don’t care enough or are not aware of it. He thinks another large edge is that Austrian Economists in general are able to understand alternative currencies much better. They are able to think about it outside of the money system just as we all think so much about the current system, that helps us for instance when bitcoin currency came up. So knowledge of Austrian Economics can provide a good investing edge sometimes in an indirect way as long as it’s utilized properly. He also discusses the potential weaknesses of using the Austrian system, saying that strictly speaking from an Austrian School, you don’t get any help regarding the timing of when we would expect to happen, however, you can still use other theories to help with that aspect. The last potential risk he discusses is that Austrians have a dogmatic bias and tend to be very cautious in an investment space.

Ethical Issues:

Russell Lamberti points out that “We all have to make a decision about leverage. In a system where debt is created by fractional reserve banks, we understand that the core of business cycle problems arises from creating debt liabilities without prior saving – this is a systemic problem. And of course when you participate in that system, there’s two ways you can look at that. You’re ether participating in the bank and leverage system as a defence mechanism against that system, but you can also argue that you’re aiding in advancing that system, so I think every investor has to answer some pretty tough questions about leverage and about the kind of leverage.” Bill Laggner agrees and adds “I think people are leaving tax-free bonds or government bonds and doing other things with their capital, getting involved with private local businesses. I don’t want to get too far off track but I think that is something clearly playing out”.

How Austrian Economics help you when looking at investments from a risk-return standpoint:

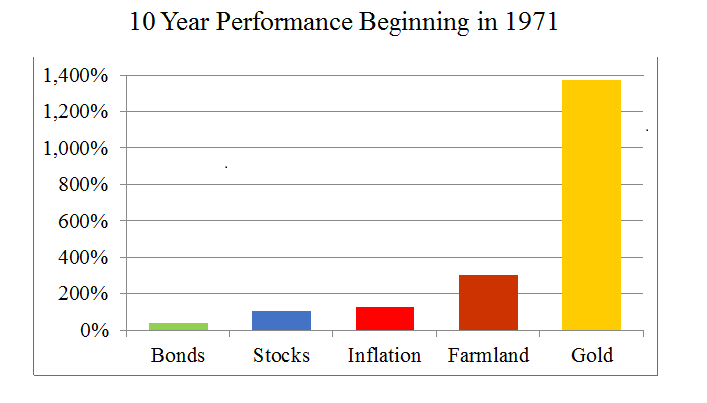

Chris Casey recalls what Mark Whitmore pointed out and added “hopefully I’m not misinterpreting him, but I believe Mark made a point that Austrian Economics doesn’t help us analyze any particular investment vehicle or perhaps even investment asset class, and by that I mean just because one company has more or less debt then another company doesn’t make it more or less Austrian. Or just because a company operates in such and such industry doesn’t make it more or less Austrian. Austrian Economics helps us because of the explanations as to inflation and recession. It helps us protect portfolios it helps us minimize risk. It also helps us profit from macroeconomic developments when they occur. Primarily meaning any kind of pops in bubbles or bond markets, whether stock or bond markets. So there you want to look for investments that will do well in that context, or that will weather the storm so to speak and do well regardless as to what happens. So you want to consider industries that potentially have high growth that will not be negatively impacted or at least will not shrink or be reduced in size through the effects of inflation of recession. Maybe you want to look at investments that historically have done well when you have inflation, meaning you want to consider gold, you want to consider farmland, things like that. So, I think Austrian Economics again helps us from an investment portfolio standpoint, minimize risk, and really seize onto some great opportunities as these things transpire. But as far as analysing any particular asset or asset class, I don’t think they lend that much value.”

Mark Whitmore adds “this notion of efficient market theory which attempts to just buy and hold the market no matter what, being completely price indifferent is clearly suboptimal. And that’s really key, as that Austrians, I think, have a sense of value in the marketplace naturally. And it doesn’t come from any unique insight of the Austrian School, other than the fact of the combination of the subjectivism coupled with the inherent boom-bust cycle makes those of us who use Austrian Economics very sensitive to issues of price and value. I think a cynic is often defined as someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing and I feel like Austrians are exactly the opposite. Whereas other investors are chasing price action if you’re somebody who’s sort of a trend follower or you’re simply buying and holding, there’s a greater tendency among Austrian investors to appreciate value.”

Websites and other information on the panelists:

Russell Lamberti: www.etmmacro.com where you can sign up for a free newsletter called “The Macro Outsider”: http://etmmacro.com/the-macro-outsider/

Bill Laggner: http://www.bearingasset.com/ and a blog at http://www.bearingasset.com/blog

Chris Casey: https://windrockwealth.com/ includes podcasts, articles, blogs and more

Mark Whitmore: http://whitmorecapitalmanagement.com includes a quarterly newsletter

Mark Valek: http://www.incrementum.li/ and he has a book called “Austrian School for Investors” available on amazon.

Abstract:

Austrian Economics takes into account the behavior of man, and has different views than traditional economic theories on monetary policy, and differs from Keynesian economics greatly on the macro level. It can also be used to identify when there is too much debt and when bubbles are in danger of bursting. Austrian Economics can be very useful for observing the overall behavior of the economy and can often help an investor make more informed decisions.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

FRA: Hi, Welcome to FRA’s Roundtable Insight. Today we have a special treat for our listeners, it’s a discussion on the principals of the Austrian School of Economics and how those principals can be used in investing. Today we have five panellists from around the world, Russ Lamberti from Cape Town, South Africa, Mark Valek from Lichtenstein, Chris Casey from Chicago, Bill Laggner form Dallas, and Mark Whitmore from Seattle.

Welcome Gentlemen

So I thought we’d have a discussion initially about what exactly is the Austrian School of Economics and how does this school of economics differ from other schools such as the Keynesian School of economics. Mark Valek, would you like to begin?

Mark Valek: I’d love to, thanks for having me, very excited to discuss basically an economic school which is from Vienna, my hometown, unfortunately Vienna, in the University doesn’t really teach Austrian Economics anymore. However, I think the topic of the Austrian School is a big one, one can talk for hours on end on how it differs, we actually tried to make the Austrian School to list the 11 of 10 bullet points, we came up with an 11th one so we could describe the Austrian school in 11 bullet points. And this is by no means a complete observational but just some basic concepts we put together, we refer to them:

- Economics is about behavior of individuals, it’s basically about human action

- They can point human innovation and entrepreneurial action of a source of wealth creation

- Private property is preconditioned for sensible resource allocation

- Trading is mutually beneficial (The Subjective value theory. Theory of Value)

- Another point would be under consumption of savings is necessary for sound investing and growth

- Also, very important point I think which differentiates the Austrian school is its view towards capital structure. So capital structure is key to a sustainable economy. Thinking about Hayek‘s triangle for the guys who know what I’m talking about here.

- And price mechanic mechanism coordinates the centralized knowledge.

So these were some basic, basic concepts and they are not only found in the Austrian School, perhaps what does differ more is the view towards the monetary system. And I just want to add 3 or 4 points regarding the Austrian view on the monetary system:

- Inflation, for instance, is defined as expansion of money supply, something very central to Austrian Economists

- Inflationary monetary systems chronically transfer wealth, I’m talking about the Cantillon effect, something I think the other schools really don’t talk about at length and it’s something very interesting for society also these days.

- And finally expanding money and credit supply causes a boom and bust cycle in the business cycle theory

So these are perhaps the more typically differentiating points, especially from the Austrians, but this list is by no means complete, just a few thoughts perhaps to put on a discussion.

FRA: And Russ you’re perspective on the Austrian School of Economics

Russell Lamberti: Yeah, well everything Mark said was valid, I would, you know at a high level I think that one of the key differentiators from a practical analytical and investment perspective was that, the Austrian school draws a very straight and consistent line between microeconomics and macroeconomics. In fact strictly speaking the Austrians wouldn’t differentiate between the two, whereas what you see in Keynesian and monetarist schools is that they have relatively sound microeconomic principals, although they do still differ with the Austrians in one or two key areas, but when they aggregate it up to the macro, a whole different theoretical framework is used and there’s essentially no consistency between neo-classical and Keynesian micro and macroeconomics so there’s a fundamental breakdown there, Austrians are far more consistent there, I think part of the sense of that is also that the Austrians school derives its lineage from the classical schools of the 1700 and 1800s. And I think we must never forget that because a very key distinction in macroeconomics, a very key departure point between the different schools of thought is what’s known as Say’s law of markets. And you know Say’s law essentially is probably a poorly named concept because Jean-Baptiste Say was not necessarily the best articulator of Say’s law. But nonetheless, Say’s law essentially says that you know, properly allocated production, production that is sustainable is ultimately what finances the ability to demand. You know, and I think that in today’s Macro world it’s only really the Austrians who are talking about the unsustainability of certain demand trends because of misallocated capital and misallocated productive resources and that’s I think why the Austrian Business Cycle is such a key distinguishing feature of the Austrian school.

FRA: And Chris, your thoughts?

Chris Casey: Well the Austrian school certainly has a number of conclusions in Macroeconomic explanations that my colleagues have discussed, but if you boil it down and ask the true question as far as what makes Austrian Economics different I’m reminded of Ayn Randwhen she was describing, or criticizing I should say, other philosophiess and philosophers. And I remember her comment I forget which writing it was, it was something to the effect of: these philosophies have excluded man from their theories, and in so doing it’s no different than, let’s say, an astrophysicist that has no concept of gravity or a doctor that has no concept of germ theory. And the same could be said with other economic philosophies. Austrian Economics is the only one that really puts man at the center of the discussion. It boils economics down to man in the context of nature as it relates to scarcity for his needs and wants. And in so doing they then use a number of first principles that build on from the deductive reasoning standpoint, create a consistent and sound economic school and economic philosophy. And that’s what really, I think, makes the difference from the other economic schools out there. It’s not just the conclusions, it’s how we arrive at those conclusions.

FRA: And Bill, your perspective on the Austrian School?

Bill: Well, look I think everyone here has covered quite a bit of the main points, I would add that the world we’re living in today where we’re very far from any Austrian practices, you cannot have a healthy economy without savings, and by artificially setting the interest rate through central banking, you set in motion numerous distortions. And I think everyone at this table would agree that we’re living at a time where the distortions have never been greater. We have nothing resembling a natural rate anywhere around the world as far as I know. And so what’s happening is your setting in motion layers and layers of malinvestment and then every time there’s a crisis in the Keynesian way of looking at things, they come to the rescue and try and either bail something out through monetary or fiscal policy and/or socialize it directly or indirectly. And I would say we’re living in a time today where so much of the credit expansion that we’ve witnessed especially coming out of the great financial crisis in 2008-2009 is a function of either zero or negative interest rates and/or socializing some aspect of credit that’s entered the economy, and when you have that, clearly there’s no feedback loop. There’s no clear natural feedback loop you have a very distorted picture of things, and I think what makes today’s investing environment very challenging.

FRA: and Mark Whitmore, your thoughts on the Austrian school?

Mark Whitmore: Well, batting clean-up here is a little tough, because as Bill mentioned, I think that people have really nicely covered a lot of the main, sort of theoretical tenants of Austrian Economics, I guess I would add that specifically the role of central banking is something that I think is really distinct from an Austrian perspective vs Keynesianism, specifically the asset price inflation that you’ve seen has largely been ignored specifically in the last two bubbles, and now we’re into a third bubble I would argue as well. And essentially the Fed and the Keynesians will continue to point to well there’s really no headline inflation pressure and hence there’s really no reason to begin to normalize or adjust or move up interest rates. And I think that from an Austrian standpoint exacerbates this boom-bust cycle which we’ve seen really compressed in terms of time verses what has historically been the case since maybe the mid to late 90s and the amplitude of bubbles to the upside has just been far greater. And I guess I would just add Henry Hazlitt’s kind of 2 points as far as critiques of Keynesianism. The first fundamental flaws being that it highlights in terms of interest, the visible minority at the cost of the invisible majority.And again it gets to this whole issue of government being the problem solver, the one that can allocate assets essentially, you know, in its view the most effectively from a Keynesian perspective in a counter-cyclical effective way, where the Austrians are much more skeptical of the efficacy of that. And second of all, the propensity under Keynesian Economics to over-consume in the present generation at a cost of creating massive debt or future debt for future generations to essentially somehow deal with, we’re sort of seeing that today in all developed parts of the world.

FRA: Great, let’s move to a discussion on how the Austrian School of economics is helpful in understanding how and why the 2007-2008 financial crisis happened. And then sort of in parallel to that, what is the Austrian School saying today about the global economy, are there any trends or outcomes that could be identified using the Austrian school. Just general question opened to the floor. Anybody?

Bill Laggner: This is Bill, I would say that all of the Austrians I’m sure on this call saw the crisis building coming out of the reflation right after the tech bubble that burst. It was interesting, the internet created this initial innovation wave decentralization wave, and of course due to excess credit creation, money creation, you had a bubble and then a subsequent bust. And then instead of letting the system purge and heal, the central banks led by the U.S. came and lowered interest rates and you segued from a technology bubble to a private sector credit bubble. And of course I think it went longer then everyone on this call thought it would, and it eventually hit a wall and again tried to cleanse and it’s interesting central banks let certain groups fail and then when things started to get out of hand, they stepped in and bailed out a number of politically connected contingents and then laid the foundation for this third bubble, and this third bubble’s gone on longer I ever imagined or my business partner imagined that it could. I think distortions are epic, I think we’re living in a fascinating time. It’s not going to end well, but I think along the way, there has been a continuation of decentralization, innovation, that’s the positive that I think we’re seeing today is as well, that’s just the natural order of the entrepreneurs and the ecosystem, they’re up.

Mark Whitmore: This is Mark chiming in here, I would say that in terms of leading up to the Global Financial Crisis I feel tremendously bad for Kurt Rickenbacker. He was I think a really fine economist, informed by sort of the Austrian School perspective and he had done a great job identifying the perils of the tech bubble that I think Bill mentioned, a lot of us who are Austrians saw coming, and died right before the bursting of the second bubble. And what he had talked about is this notion of “Ponzi finance” that I think is good analytical insight that Hayak also talks about which is essentially the boom-bust cycle is endogenous to the particular type of finance credit system you have in place, and this credit can become increasingly untether any kind of historic connectors to things such as sound collateral and whatnot you saw increasingly these signs of the economy going off the rails in the upward direction in a trajectory that was simply unsustainable. So indeed that bubble went longer than most of us expected, and this one is truly epic, there’s one slide that I drew up which essentially overlays the growth of S&P 500 with the growth of central bank assets in Japan, the Eurozone, and the United States.

* Includes the US, ECB, BOJ and PBoC.

Sources: Yardeni Research, Inc. (www.yardeni.com); Haver Analytics

The assets of these central banks have been expanded a little bit more jagged but the curve, the direction and amplitude of the line is almost exactly the same and so you see this again, unsustainable credit fueled engine that’s driving what’s been taking place in terms of asset price inflation.It’s just highly unstable, and again this will not end well.

Russell Lamberti: Hey it’s Russ, I just wanted to chime in on what Bill had mentioned, I think it’s really critical to look at this as three very big bubbles in a row, but also to think about the compounding effects of repeated malinvestment that has been essentially dis-allowed from correcting and from reallocating promptly. There’s basically been since, I don’t know how long, maybe it was the Greenspan era that essentially ushered us in. But there’s essentially an unwritten law against recessions. And this is not just a problem in America, this is a problem everywhere in the world. Politicians don’t like recessions. As they push back through repeated cycles we have chronic malinvestment, chronic poorly allocated capital. And this creates a hostile working lifetime of living in an essentially very strange unreal financial and capital structure. But of course, as Bill rightly says, you have the countervailing forces of progress constantly working, the market is constantly trying to figure out how to make the best of its present reality and its present situations. This is why I think you have inherent paradoxes when you look at these big cycles, because there is so much to be bearish about, and yet there’s also a lot to be bullish about, and I guess that’s the essence and the nature of risk and opportunity. You know Mark Thornton once mentioned that Murry Rothbard used to say he was permanently bearish about the short term and permanently bullish about the long term. And I think that it’s an aphorism, but it kind of speaks to this notion that state intervention can really mess up markets and financial markets in the short term. But over time the power of the free market and of private enterprise is extremely pervasive and eventually seems to win out at the end of the day. Of course in the interim what that means is that because you have such disinflationary forces because of private enterprise and technology, it kind of emboldens the policymakers to run these bubbles longer and larger than they should be, so no question that the last two bubbles have been a symptom of these kind of policies, and I agree, we’re in a third very excessive state of distortion and the best case scenario that we can hope for is a sharp, painful clear out of chronic malinvestment. That is the fastest path to genuine economic progress again. I hope we get there soon.

Chris: This is Chris, I’ll just add that in discussing how Austrian Economics explains the 08 crisis gives us some guidance to future bubbles in economic recessions, it’s worth recounting what does not explain the 08 crisis, and that is mainstream economics. Whether it’s so-called Chicago or Keynesian schools. And it’s probably worth remembering that in 2002 at Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday party that Ben Bernanke stood up and literally apologized for the Great Depression, and he basically said “We’re never going to have a significant recession again.” I believe he said something to the effect of “we won’t do it again” and so that tells you central bankers pretty much around the world do not understand the causes of recessions at its most fundamental level. They can’t explain why it occurs, they can’t explain why it’s a cycle, they can’t explain what Austrians call “the cluster of error”, why all these businesses have made horrendous investment decisions. They can’t explain why every recession is proceeded by monetary inflation, they can’t explain why certain industries are far more cyclical then say consumables. So it’s just something that cannot be explained, the Austrians do, and for the listeners who may not be all that knowledgeable on the Austrian School, in short, whenever you inflate the money supply, you are decreasing interest rates which distorts the whole structure of production, it forces economic actors to make investments they would not have otherwise done, that they would have otherwise deemed unprofitable, and it creates this malinvestment in the system, as my colleagues here today mentioned, we’ve already seen this play out twice in the last 20 years. And the response, if that’s the causation of a recession, the response should be hands off. The response by the government and central banks should be to not re-inflate the money supply, do not create bailouts, not have deficits which only will spur consumer spending at the expense of savings. So if that’s the antidote for recessions, the governments since the 08 crisis has done the exact opposite and it’s simply set up the economy for far, far greater downturn then what we even experienced (in 2008), with the possibility of significant inflation. So the 08 crisis gives great lessons and basically proves out the Austrian theory, the business cycle. And it really demonstrates errors and issues with other explanations from other economic schools of thought.

FRA: and Mark Valek, any thoughts on applying the Austrian school to the financial crisis and where we’re potentially heading today and the Global economy?

Mark Valek: Definitely some thoughts, very short though because again, a lot has been said already. Where are we going in the Global Economy? Providing you have the Austrian perspective as we all obviously have, you actually know that there are significantly high (inaudible) to the capital structure, and this is not a sustainable state. But there lies the problem for investing obviously, the timing question, but sooner or later this state of capital structure will not last, it’s absolutely not sustainable. Just on a side note, as an asset manager, I encounter sustainability so many times a year, it’s kind of a hyperinflated world, everybody wants to invest sustainably and what bugs me that is nobody things about if our, for instance, monetary system is sustainable, and I would argue against it. So this is to me, really a very superficial discussion here. However, I think if this cleansing process starts the next time, we will probably will not see the big fear we saw the last time, which was basically the fear of deflation of debt deflation if you want to call it, like debt. I think the authorities have proven that they just will not let this happen so market participants probably are not going to have fear that will be too little money going around or being printed, but perhaps we’ll start to fear that this is going to be an overdose the next time, and I think as soon as this psychology changes, you have (Inaudible) things like price inflation look much more realistic in such an environment if you ask me.

FRA: Great insight, and so given this view of applying the Austrian school to the economics environment, if we can consider that as far as the investment environment, does it make sense to look at the principals of the Austrian school in investing, I mean, we see some of the principals, of being stores of value, indirect exchange method, meaning exchanging fiat currency for investments that are real assets that provide cash flows, investments with little or no debt, high free discounted cash flows as well. Little or no leverage, also scarcity in innovative industries, and then perhaps cryptocurrencies that are outside of the banking system but are still regulated within the financial system. So does it make sense to apply those principals in investing, and what are those principals? Also, are there any empirical studies or analysis that taking this approach can provide an edge or an enhanced investment management performance? This question is for the floor.

Bill Laggner: This is Bill, I could say I think knowing the Austrian business cycle theory is helpful in fact, during the second bubble, the credit bubble, I wrote an article with a colleague called “collateral damage”. And what was fascinating about writing the article was we had created the Bearing Credit bubble index back in 2004 when it was pretty obvious that we were segueing into this new bubble, and I kept looking at the types of asset-backed securities are being created mainly, and mortgage arena, and then the derivatives wrapped around it, and then attended a few conferences. But I started focusing on the collateral because it’s a confidence game, right, I mean people have confidence when these troubles start, they grow and what was interesting was in 2005 the home-builders had started declining severely and writing down land values ext. but subsequent to that you had maybe 12-18 months of watching paint dry. I mean the other related industries kind of kept chugging along. And it wasn’t until early 07 where the secondary market for certain types of mortgage-backed securities just locked up. And that was the beginning of the end. So to me, when I look at excess credit creation through the socialization of credit by the central bank and or other government agencies like Fanny and Freddie in the U.S. I was looking at collateral that was kind of a helpful sign that we were near some kind of inflection point. I think what makes this cycle so much more difficult, and look full disclosure I mean we’ve had a net equity short bias for the last several years, and it’s been pretty painful. I think this cycle because they’re all playing the same game, they’re all in together. Is there any limit to what the central bank balance sheets can go to? I mean, how many bonds can the central bank give Japan or the ECB or the Fed purchase, and I think it’s pretty clear that since all the chips are in the middle of the table, they’re going to continue to buy bonds, and try and hold certain parts of the yield curve suppressed to keep the game going. So ultimately I think you know gold, we own a lot of gold, we’ve owned gold since 2002, I mean gold will continue to act well, and may become one of the best performing asset classes over the next several years until we ether get some kind of boom or something close to it. So that’s how it’s helped us and how we employ it in day to day portfolio management.

Chris Casey: This is Chris, I’ll say that I’m not sure if Austrian Economic principles are necessarily applicable to investing, but Austrian Economic conclusions certainly are. They certainly are as they relate to the macroeconomic phenomena of recessions and inflation. Because these are the two forces that create the greatest risk factors regarding ones investment portfolios. The recessions are going to pop any bubbles that are out there pushing the equity markets, and inflation will destroy the bond markets. And when you’re looking at equities or bonds, these obviously make up, for most people, the vast majority of their investment portfolio or at least the core of the investment portfolio. So if you’re able to use Austrian economics to navigate these two risk factors, I think it presents a tremendous advantage for investing. As far as whether or not there’s been empirical evidence demonstrating this, not to my knowledge, I think it would be difficult to construct such a study for a couple reasons. One being the time period that we’re looking at. Austrian economics hasn’t been utilized in this form for very long. And secondly would be the sheer number of people using Austrian Economics in this fashion. It’s very limited set. The people here in the call know that they represent a good portion of that universe, may be the universe, of people managing money with Austrian Economic concepts in mind. So there are very limited data points out there.

Mark Whitmore: This is Mark, I would sort of follow up on Chris’s comments. I tend to also be somewhat skeptical as far as can you look at Austrian Economics as instrumental tools for specific kinds of investment analysis or recommendation. And I think that’s a harder thing to make a case for. What I think is incredibly valuable, is how do you explain reality and in essence, the kind of the largest school out there in terms of money management is the efficient market theory, this idea that whatever the price of the given asset is at any time, it’s the “right price”. Because all the information is being priced in so trying to outguess the market is kind of a fool’s errand. And I think that one of the most basic, the most essential insight of Austrian Economics is this idea of subjectivism, and that prices are wholly derived by human beings, and one of the other schools of economic thinking that I think dovetails nicely with the Austrian school is Economic behaviorism, this idea that individuals are driven by greed and fear, and as a result, and this feeds very much into the boom bust cycle of the Austrian framework, that you get these ridiculous, unexplainable run-ups that leads to catastrophic losses. And if investors can simply, instead of, and I remember reading one of the most tortured treatments by Burton Malkiel who wrote the seminal Random Walk Down Wall Street which is sort of like the bible of efficient market theory, and soon after the edition following the 1987 stock market crash where the Dow went down 20% in a day, he attempted to try to explain how this was a rational response to changing monetary conditions, and the market was kind of correctly pricing things all the way along. And you find these things which, I think Chris mentioned earlier simply that Keynesians and the people who look at kind of classical economics and efficient market theory, they can’t explain reality. But the power, the strength of Austrian Economics you can see bubbles when they’re coming. And like Bill, I’ve leaned into the defensive positive in the last few years, so in the short run you might seem to be looking like a fool, but if you can help your investors avoid and maybe even profit from bubbles as they unwind, you’re going to be far better off than the vast majority of investors out there that are just being caught up and are losing 50% of their portfolio in multiple stretches.

Russell: Hey guys, its Russell here, Mark you’ve just made some really great points. And I think I would echo a lot of what you said. I think it’s about creating a coherent perspective of macro-reality, you know there’s so many investment firms, you go on their websites and they talk about how they like to find miss-priced assets, because they believe that the market doesn’t always effectively price assets. But they’ve never really got a coherent reason why. I think the nature of clusters of error of boom and bust cycles, of the business cycle creates a very coherent reason why you get big distortions and big mispricing. And what I try to do for my clients is I say to them that ultimately using Austrian principals is essentially about creating a coherent perspective of reality, and also using that coherent perspective of reality and comparing it to the market narratives that emerge. Donald Trump gets elected, and there’s a narrative there that emerges, a reflationary narrative. A narrative might be that he’s going to deregulate and the market finds an excuse to run even higher. And you’ve got to kind of test all these market narratives against really sound perspectives of reality. In addition to that I’d say a few things one is that an Austrian perspective gives you an understanding that you’re not in a free unfettered market, you’re in a market where the state plays an incredibly dominant role and is essentially trying to plunder private resources. And so a huge element of investment strategy from an Austrian perspective has to be the sense that you are defending your wealth against the plunderers. The second component is that business opportunities can be false, and that’s something that’s embodied in the essence of boom-bust cycles, subsidization, and the principals of Say’s Law, you know expecting consumer markets to boom when in fact you’ve got misallocated productive capital, those consumer markets are not going to perform how you expect. And the flip side of that of course is that you get overestimated business risk, because some people are avoiding sectors that look unattractive when in fact they are fundamentally attractive, particularly if they can exploit state failure. And then finally Hayek spoke about the pretense of knowledge in his famous Nobel acceptance speech, and you know one of the things that none of us, whether you’re an Austrian or not, none of us have the entirety of knowledge that we need to make very precise and accurate calls about the investment world. And that’s one of the reasons why, and it’s spoken about in the book “Austrian School for Investors” but you know you’ve got to start off by exploiting opportunities as an investor that are close to you. That you’re capable of having knowledge about, and that’s why before you invest in public companies and in funds, you probably have to invest in yourself, in your own entrepreneurship or in private equity opportunities that are very close to you and where you have some special knowledge. Because you don’t have any more knowledge then the central planners do either. So I think those are some really key objectives. I think there’s some ethical issues as well but I don’t want to go into that right now, but I do think that when we talk about Austrian Economics being free of value judgment, that’s very much in the theoretical analytical sense. But once you’ve derived conclusions from that, value judgments definitely come to the fore, and I think there’s a strong ethical component that can be informed across a range of asset classes and how you invest and how you go about investing. I’m going to not go into that right now, we can maybe circle back to that a bit later.

FRA: Then Mark Valek, as Russ refers to your co-authored book on the Austrian School for investors, can you provide some insight from that book on these principals?

Mark Valek: Yeah thanks. Just a small supplement here, we thought about this topic very hard and we thought, where potential opportunities lie in Austrian investing and where do potential risks lie in such a discipline. Just a few words on opportunities we’ve heard I think already in that direction. The fact that it’s not read among investors. I think that’s potentially a huge edge, it’s a huge edge in a marketplace where it’s not really a secret, it’s out there, you just have to read it on the internet, go on mises.org or wherever, but most of the people just don’t care or know about this so it’s not read. Second edge knowledge about Austrian business cycle theory we also talked about, but I just want to point out the third edge which we identified and I think Austrians in general are able to understand alternative currencies much better they are able to think about it outside of the money system just as we all think so much about the current system that helps us for instance when bitcoin currency came up, I was not even as a tech guy but just from an Austrian view I was able to pretty fast wrap my head around the basic concepts. And I knew if this thing monetizes then it’s huge financial gain and if it doesn’t well until it does it’s speculation on a potential alternative money, but now I think it’s more clear to the rich investor too, but such thing I think come with an Austrian mindset. On the other hand just also to talk about the risks perhaps for one moment with Austrian investing, generally, and I’m sure all of us know about this potential risk, is a bearish bias is associated to the Austrians. I think that’s because Austrian investors are sensitive to these flaws in the capital structure we already talked about. And they always kind of think perhaps this boom will be bust sooner than later and so on, and we know the problems I think associated with that. Another problem I also touched already is the Austrian School statistic it does not make timing calls. So this is a predictive problem obviously, especially in finance. I think one can circumvent this problem with the help of other techniques from the quantitative side take the analysis, whatever. But strictly speaking from an Austrian School, you don’t get any help regarding the timing problem. Just to mention the last potential risk, Austrians do tend to be very convinced, it’s like what we call potentially a dogmatic bias, and dogmatism is probably a thing where one should be cautious in an investment space. So there are other opportunities, but there’s also risks and one should be aware of these risks and find some ways to manage these risks as an Austrian investor.

FRA: If we could do one more round on bringing it all together and providing some examples of investments or asset classes or perhaps investment strategies that exemplify using the principals of the Austrian School in investing or the outcomes as Chris mentions, of the Austrian School. Let’s do a round based on that to close out. No specific companies or securities, but just generically speaking. Anybody?

Russell: It’s Russell here, maybe I can come in and say one or two things about some of the ethics around investing. I mean, we all have to make decisions about leverage. In the system where debt is created by fractional reserve banks we understand that the core of business cycle problems arises from creating debt liabilities without prior saving – this is a systemic problem. And of course, when you participate in that system, there’s two ways you can look at that. You’re either participating in the bank leverage system as a defense mechanism against that system, but you can also argue that you’re aiding in advancing that system, so I think every investor has to answer some pretty tough questions about leverage and about the kind of leverage. I think from an Austrian perspective, you would typically favor equity over debt and you would favor non-bank debt over bank debt. The other big ethical question, of course, is to talk about government bonds – financing the state. The state is essentially a mechanism of wealth destruction, you know do you really want to be financing plunder, but in another sense, by funding the state, you’re again, aiding and abetting a fairly large degree of wealth destruction. And ultimately getting your coupon payments in part by being taxed more and your friends and family being taxed more. So one’s got to think about that, some of these issues. And then, we know that Ludwig von Mises was one of the greatest advocates for peace, and anti-war, and you have to think about what firms are doing in terms of financing and funding and equipping governments to fight unjust wars. These are obviously very tricky and murky. And I’m not trying to make any kind of high-brow ethical statements here, I just think that these are the kind of things that have to be considered and Austrians do think a lot about these things. So I just wanted to kind of lay that out there, because ethics and feeling personally good about your investments, not just intellectually, but emotionally as well, I think is an important part of an investment strategy.

Bill: This is Bill, I’d like to just touch on something Russell mentioned, great points by the way, the state has grown immensely around the world subsequent to 2009. And I don’t want to get to far into the metrics we all know what played out in certain parts of the world, I think one of the beauties of the internet and the search for the truth and leading us to the election in the United States for example last year in WikiLeaks, the internet is essentially exposing a lot of the fiction that we’ve all grown up around over the last number of decades. And with that comes almost an awaking, a move to higher consciousness. So people are, I see it every day, I think people are leaving tax-free bonds or government bonds and doing other things with their capital, getting involved with private local businesses. I don’t want to get too far off track but I think that is something clearly playing out. Cryptocurrencies, I’ve spent a lot of time looking at the economic actors within this interesting ecosystem and you think about not being a participant in the plunder if you look at just the banking system and all of the friction within the banking system, let alone the leverage, you’re looking at a couple trillion dollars a year just in general friction that’s being stripped out of the ecosystem. So the movement towards the internet of value as opposed to what we witnessed the last couple of decades, the internet of information knowledge I think is another fascinating innovation playing out. So I think more and more people per Russell’s point, don’t want to participate in the plunder and are actually spending time and capital creating these new economic fabrics and I think it’s quite exciting to witness.

Chris: This is Chris, if we take out the ethical considerations that a couple of my colleagues just mentioned, the question is how Austrian Economics help you when looking at investments from a risk-return standpoint. And I think Mark mentioned this earlier, hopefully I’m not misinterpreting him, but I believe Mark made a point that Austrian Economics doesn’t help us analyze any particular investment vehicle or perhaps even investment asset class, and by that I mean just because one company has more or less debt then another company doesn’t make it more or less Austrian. Or just because a company operates in such and such industry doesn’t make it more or less Austrian. Austrian Economics helps us because of the explanations as to inflation and recession. It helps us protect portfolios it helps us minimize risk. It also helps us profit from macroeconomic developments when they occur. Primarily meaning any kind of pops in bubbles or bond markets, whether stock or bond markets. So there you want to look for investments that will do well in that context, or that will weather the storm so to speak and do well regardless as to what happens. So you want to consider industries that potentially have high growth that will not be negatively impacted or at least will not shrink or be reduced in size through the effects of inflation of recession. So maybe in America you want to consider the cannabis space. Maybe you want to look at investments that historically have done well when you have inflation, meaning you want to consider gold, you want to consider farmland, things like that. So, I think Austrian Economics again helps us from an investment portfolio standpoint, minimize risk, and really seize onto some great opportunities as these things transpire. But as far as analysing any particular asset or asset class, I don’t think they lend that much value. I’ll also say that I think Austrian Economics lends itself naturally to contrarian investing which I think is a great way to make money. It’s pretty obvious that there’s not a lot of people out there managing money that believe in Austrian Economics. So we hold a key, we understand something that few people embrace or have any kind of knowledge of. And I think that really is a key factor in contrarian investing which really just means you’re looking for extreme market value questions on the high or low side, and identifying the catalysts that will bring that prices back to its historical mean or median. And I think the explanation and conclusions of Austrian Economics do that quite well.

Data Courtesy of the St. Louis Federal Reserve

Mark Whitmore: This is Mark Whitmore, I keep forgetting we have two Mark’s on the line here, and Chris you absolutely interpreted what I was trying to say correctly, and kind of to follow up a little bit, I think one of the things that the other Mark pointed out is the issue of timing, and whereas the two prevailing investing paradigms out there seem to be this notion of efficient market theory which attempts to just buy and hold the market no matter what, completely price indifferent. And that’s really key, is that Austrians I think have a sense of value in the marketplace naturally. And it doesn’t come from any unique insight of the Austrian School, other than the fact of the combination of the subjectivism coupled with the inherent boom-bust cycle makes those of us who use Austrian Economics very sensitive to issues of price and value. I think a cynic is often defined as someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing and I feel like Austrians are exactly the opposite. Whereas other investors are chasing price action, if you’re somebody who’s sort of a trend follower, or you’re simply buying and holding, there’s a greater tendency among Austrians to appreciate value. And this point dovetails with the other point as far as since we don’t pretend to know the precise timing of when bubbles kind of unwind or when the busts will finally reach a bottom, the idea is that we can actually be in the right quartile of activity, in other words I never try to catch the very top of a bubble, I don’t try to ride things to the very end, and similarly I don’t mind catching falling knifes. Because as investors if you’re looking at this current contemporary global macroeconomic backdrop from the 10-12 year perspective, I find it with the typical disclosure here that I’m not able to see with a perfect crystal ball or anything but it’s hard to believe that traditional assets, that global equities, will be thriving in this environment just from the simple perspective of how overstretched they are from any reasonable measure of valuation. And similarly, the global bond market which has been the classic offset to unwinding stocks in the past, is also so stretched.Because just like bond prices are inversely related to interest rates, you have interest rates around the world, I mean you have negative interest rates in Sweden, in Japan, in Switzerland, and back last July you have negative interest rates over a swath of different developed markets so there’s simply not a lot of room basically for bond appreciation. I think it’s a very careless time for equity and bond investors from a longer term perspective whereas those of us who are Austrian have a bend for the idea of real money, sound money, and one of the things that looks pretty attractive in a Ponzi finance global macroeconomic backdrop would be precious metals I would say. And I particularly play in the currency space and one of the thing that’s attractive there is the idea that in eras where you have reckless central banking there’s huge distinction between reckless central bankers and those who are engaged in reckless central banking with abadon and as a result I think that there becomes some real value disparities from a currency standpoint as well. But I mean I think that’s how I at least use Economic principals from the Austrian school to inform overall investing decisions in the marketplace.

FRA: And finally, the other Mark?

Mark Valek: Yeah, I think that most points have been touched seriously. Yeah I just don’t want to drag it out unnecessarily, but I think there were very interesting comments in all kind of directions, really enjoying this discussion, I don’t know if we have anything else on the plate?

FRA: Nope, that’s it. Just wanted to close out with regard to giving everybody a chance to identify how our listeners can learn more about your work, if you have a website or perhaps a newsletter?

Russell Lamberti: Yeah my website, ETM macro advisors website is www.etmmacro.com and I am starting a new newsletter called the macro outsider, and you can sign up for it for free on www.etmmacro.com and you’ll get a free essay called “The real currency war” which is subtitled “monopoly money vs real money” and essentially there I just go into a lot of what we’ve spoken about today in terms of chronic malinvestment, the weakness of fiat currency reserve systems, and then ultimately where I think the real currency war is, which is in centralized vs. decentralized money, and I talk a little bit about cryptocurrencies there as well, so that’s www.etmmacro.com you can sign up for that free newsletter.

Bill Laggner: This is Bill, so Kevin Duffy and I, we manage a couple of funds, long short-biased, I should say long short strategy macro oriented funds, bearing asset, like ball bearing .com, http://www.bearingasset.com/ and then we also write a blog http://www.bearingasset.com/blog and then Kevin and I are on twitter as well, we post some comments from time to time.

Chris Casey: This is Chris Casey with WindRock Wealth Management, we manage money for high net worth individuals. I would encourage anyone that wants to check us out just to visit our website https://windrockwealth.com/ We have our contact information there, we have all of our content, meaning podcasts, articles, blogs etc. That’s been posted since we started the firm and the people can feel free to read more about our philosophy on various issues.

Mark Whitmore: Great, and this is Mark Whitmore in Seattle, I have a website at http://whitmorecapitalmanagement.com there’s a research and article section which has, I do a quarterly newsletter and would be happy to put anyone interested on the mailing list for that, and basically we have a strategic currency fund that is again, informed largely by Austrian Economic principles that I operate. I also will make a plug here for one of my co-panellists, Mark Valek, who has his book “Austrian School for Investors” is essentially that he co-authored is one of the only kind of resources out there that’s an outstanding resource and really well researched and thought out, so I want to complement the fine work you’ve done on that.

FRA: Great, and now Mark Valek

Mark Valek: Thanks so much, thank you if you’re interested the book is on amazon I guess, “Austrian School for Investors” our homepage is http://www.incrementum.li/ we’ve got lots of good stuff which is relevant up there, first of June our annual “In gold we Trust” report is going to be published as well. You’ll find that on the homepage as well.

Summary and Transcript by Jacob Dougherty jdougherty@Ryerson.ca

04/11/2017 - The Roundtable Insight: 5 Top Money Managers Discuss Austrian School Investing – Now Published

04/11/2017 - The Roundtable Insight: 5 Top Money Managers Discuss Austrian School Investing – Now Published