FINANCIAL REPRESSION: How to Lift Markets by Stealth Lowering of the Regulatory Risk Hurdles

There are many ways to raise market prices but none is easier than relaxing regulatory rules originally enacted to protect the unsophisticated and unsuspecting. Historically, events associated with financial crisis have normally resulted in new regulations intended to avoid another similar crisis. Today the reverse is practiced to keep markets rising and avoid the unwinding of excessive and pyramiding debt leverage.

Let’s examine four major regulatory pillars that rose from the ashes of financial destruction and which today, as part of Financial Repression, have been removed or minimally “neutered” by regulators.

- US Anti Trust Laws – The 1890 Sherman Act

- US Bank Reserve Requirements –

- US Separation of Banks and Financial Institutions – The Glass-Steagall Act

- Mark-To-Market Derivative Valuations

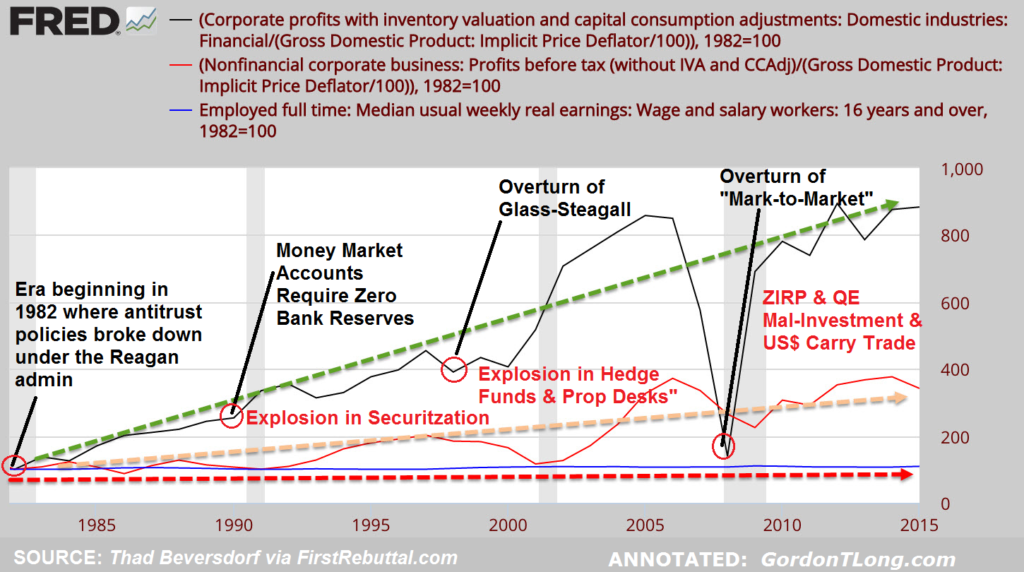

You will notice in the graph below that all four regulatory reversals were changed which resulted in rising profits for the Financial Markets and Wall Street, while Main Street and the US Middle Class was left in the wake.

US ANTI TRUST LAWS – The Sherman Act

Approved July 2, 1890, The Sherman Anti-Trust Act was the first Federal act that outlawed monopolistic business practices. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts. At the time individuals like John D Rockefeller and his Standard Oil corporation had taken control of industries and had almost uncontrollable power over pricing, potential competitors and politicians.

Approved July 2, 1890, The Sherman Anti-Trust Act was the first Federal act that outlawed monopolistic business practices. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts. At the time individuals like John D Rockefeller and his Standard Oil corporation had taken control of industries and had almost uncontrollable power over pricing, potential competitors and politicians.

Up until Ronald Reagan took control of the White House these laws were rigorously enforced as witnessed in the late 70’s by the breakup of AT&T into the Regional RBOCS and even the decade long attempt by the justice department to breakup the then dominant technology leader, IBM. Major corporations were under fire until the early 80’s when a more relaxed lassie-fare attitude crept in with pro-corporate sentiment. That is when the graph above begins and when the stage was set for what has resulted in blatant Crony Capitalism today dominant players controlling the Media, Military-Industrial Complex, Big Pharma, The Security-Surveillance Complex etc.

US BANK RESERVE REQUIREMENTS – Removal of Reserve Requirements for MM, CD, Time Deposits & Foreign Deposits.

The Federal Reserve requires banks and other depository institutions to hold a minimum level of reserves against their liabilities. Currently, the marginal reserve requirement equals 10 percent of a bank’s demand and checking deposits. A money market account is a savings account that allows a limited number of checks to be drawn from the account each month and just after the 1987 Financial Crisis the regulatory banking reserve requirements for Money Market accounts was summarily removed. Then effective 27 December 1990, a liquidity ratio of zero was applied to CDs and time deposits, owned by entities other than households, and the Euro currency liabilities of depository institutions. Deposits owned by foreign corporations or governments are now currently not subject to reserve requirements.

These are profound changes to the banking industry which fostered major increases in leveraged lending.

SEPARATION OF BANKS & FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS – The Glass-Steagall Act

The Glass-Steagall Act, also known as the Banking Act of 1933 (48 Stat. 162), was passed by Congress in 1933 and prohibits commercial banks from engaging in the investment business. It was enacted as an emergency response to the failure of nearly 5,000 banks during the Great Depression.

The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLBA), also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, is an act of the 106th United States Congress (1999–2001). It repealed part of the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933, removing barriers in the market among banking companies, securities companies and insurance companies that prohibited any one institution from acting as any combination of an investment bank, a commercial bank, and an insurance company. With the bipartisan passage of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, commercial banks, investment banks, securities firms, and insurance companies were allowed to consolidate. Furthermore, it failed to give to the SEC or any other financial regulatory agency the authority to regulate large investment bank holding companies. The legislation was signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

A year before the law was passed, Citicorp, a commercial bank holding company, merged with the insurance company Travelers Group in 1998 to form the conglomerate Citigroup, a corporation combining banking, securities and insurance services under a house of brands that included Citibank, Smith Barney, Primerica, and Travelers. Because this merger was a violation of the Glass–Steagall Act and the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, the Federal Reserve gave Citigroup a temporary waiver in September 1998. Less than a year later, GLBA was passed to legalize these types of mergers on a permanent basis. The law also repealed Glass–Steagall’s conflict of interest prohibitions “against simultaneous service by any officer, director, or employee of a securities firm as an officer, director, or employee of any member bank”.

This was the official start to anything goes in the banking industry until it imploded in 2007-2008 with the financial crisis predicated on banks no longer owning the loans it peddled and made more money on its “prop desks’ which Dodd-Franks subsequently attempted to stop.

This was the official start to anything goes in the banking industry until it imploded in 2007-2008 with the financial crisis predicated on banks no longer owning the loans it peddled and made more money on its “prop desks’ which Dodd-Franks subsequently attempted to stop.

MARKET-TO-MARKET – Derivative Valuations

Mark-to-market or fair value accounting refers to accounting for the “fair value” of an asset or liability based on the current market price, or for similar assets and liabilities, or based on another objectively assessed “fair” value. It was done away with during the financial crisis on a “temporary crisis basis”. It has never been reinstated.

Fair value accounting has been a part of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in the United States since the early 1990s, and is now regarded as the “gold standard” in some circles. Mark-to-market accounting can change values on the balance sheet as market conditions change. In contrast, historical cost accounting, based on the past transactions, is simpler, more stable, and easier to perform, but does not represent current market value. It summarizes past transactions instead. Mark-to-market accounting can become volatile if market prices fluctuate greatly or change unpredictably. Buyers and sellers may claim a number of specific instances when this is the case, including inability to value the future income and expenses both accurately and collectively, often due to unreliable information, or over-optimistic or over-pessimistic expectations of cash flow and earnings.

It it any wonder that Wall Street financial asset “pushers” never want to see it again!

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN – Strangling the Competition

We could have cited other examples of how relaxed regulatory requirements have been a boon for Wall Street, Banks and Financial Intermediaries. We would be amiss not to point out that in fact the use of regulatory laws (versus removing them), in the form of “Regulatory Arbitrage” has become a mainstay for corporations to stymie competition andn “build mots” around their business models. This is done through massive lobbying efforts as a corporate strategic imperative.

08/31/2016 - FINANCIAL REPRESSION: How to Lift Markets via Stealth Lowering of Regulatory Risk Hurdles

08/31/2016 - FINANCIAL REPRESSION: How to Lift Markets via Stealth Lowering of Regulatory Risk Hurdles