FRA Co-founder Gordon T. Long is joined by Satyajit Das in discussing the consequences of financial repression and current policy making, along with the effects of the Chinese economy.

SATYAJIT DAS is an internationally respected expert in finance, with over 35 years’ experience. Das presciently anticipated many aspects of the global financial crisis in 2006. He subsequently proved accurate in his warnings about the ineffectiveness of policy responses and the risk of low growth, sovereign debt problems (anticipating the restructuring of Greek debt), and the increasing problems of China and emerging economies. In 2014 Bloomberg nominated him as one of the fifty most influential financial thinkers in the world.

Mr. Das is the author of a number of key reference works on derivatives and risk management. Das is the author of two international bestsellers, Traders, Guns & Money (2006) and Extreme Money (2011). His latest book is A Banquet of Consequences (2015) (published in North America as Age of Stagnation).

He was featured in Charles Ferguson’s 2010 Oscar-winning documentary Inside Job, the 2012 PBS Frontline series Money, Power & Wall Street, the 2009 BBC TV documentary Tricks with Risk, and the 2015 German film Who’s Saving Whom.

VIEWS ON FINANCIAL REPRESSION

It started around 2008 and prices relate to debt. Fundamentally, the way the surprises were dealt with were in a very old fashioned way to grow and inflate their way out of debt. As we know, this process hasn’t really worked, and there’s really only two choices left. One of them is to default, which is hugely unpalatable because writing off peoples’ savings like that has consequences for future consumption, and a huge amount of wealth loss in the world. The other option is financial repression, which is a way of managing excess debt. The most common way is by very high levels of taxation.

It started around 2008 and prices relate to debt. Fundamentally, the way the surprises were dealt with were in a very old fashioned way to grow and inflate their way out of debt. As we know, this process hasn’t really worked, and there’s really only two choices left. One of them is to default, which is hugely unpalatable because writing off peoples’ savings like that has consequences for future consumption, and a huge amount of wealth loss in the world. The other option is financial repression, which is a way of managing excess debt. The most common way is by very high levels of taxation.

“I don’t think people, when talking about financial repression, are talking about taxation as being something that shouldn’t happen.”

There’s obviously a point of taxation which is to run social services and infrastructure and government, but at some point under the condition of high debt it starts to bring taxation rates up for the simple reason of using the state to absorb everyone’s debt, in other words socialize the debt and then try to use the taxes to pay it off. That can be hugely unproductive for the economy but we’re starting to see it happen around the world.

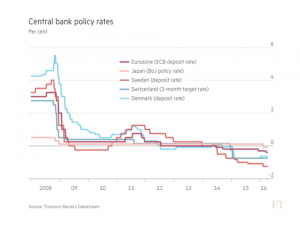

The next stage is what we call financial repression, where we start to devalue the debt. The most important way we can see that is through a period of low interest rates.

“People forget that since 2008, we’ve had over 600 interest rate cuts globally. Interest rates are pretty much around zero around the world.”

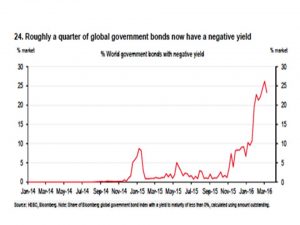

Roughly 30% of global government bonds are trading at negative yields. Either you have nominal yields that are positive but below the rate of inflation to use that to try and ease the purchasing power of debt. Alternatively as we’re now finding that because inflation is low and the debt levels are so high, we’ve gone to negative interest rates. There’s something perverse about negative interest rates because people get very technical about it. This is actually a way of writing down the debt, and are very dangerous, as the market’s reaction to the negative interest rates in Japan and Europe have proven.

Roughly 30% of global government bonds are trading at negative yields. Either you have nominal yields that are positive but below the rate of inflation to use that to try and ease the purchasing power of debt. Alternatively as we’re now finding that because inflation is low and the debt levels are so high, we’ve gone to negative interest rates. There’s something perverse about negative interest rates because people get very technical about it. This is actually a way of writing down the debt, and are very dangerous, as the market’s reaction to the negative interest rates in Japan and Europe have proven.

Firstly, there’s no real proof that these types of policies are going to create growth or inflation. They’ve been put in place to write down the debt. First we have -5% interest rates, and after ten years we’ve written off half the debt. That’s now a sort of stealth tactic the central banks and policy makers have put in place. Everybody knows that they said, look, in the next crisis we’re going to cut interest rates and interest rates are so low that we’re going to have to go to negative territory, but we all know that if we go to negative territory people are just going to take money out of the bank and just hold the cash.

“They’re going to have to stop people from taking out cash, and the interesting way that’s being channeled by policy makers is that they’re pretending that banning cash is necessary to prevent criminality or terrorism.”

There are also other forms of financial repression as well, like redirecting investment. There’s a whole variety of these measures that we see come into play, and it all has to do with the fact that they try to use these measures to deal with the debt crisis.

“I would argue that it’s not going to be able to be dealt with, and it creates enormous social and political pressures… What we’re going to see is a period of financial repression, which is very, very dangerous.”

POLITICAL EXTREMISM AND POLICY MAKING

We’re starting to see signs of this via the political extremism that’s starting to come about. The reason these popular extremist policies are being promoted in the United States and elsewhere is because financial repression and the lack of honesty of dealing with the world’s financial and economic problems.

If you look at this period of history and the way the Europeans have deal with the European Debt Crisis, it’s almost single-handedly created parties like Ciudadanos in Spain, but in Germany these policies would never have gotten any sort of traction. Even the German Finance Minister has said that these parties are really the creation of the economic policies that people are playing around with, and that’s setting up this confrontation we see in play between Germany and the European Central Bank.

“I honestly don’t know how it’s going to end. In the 1920s and 1930 when similar pressures built up, it didn’t actually have a very good ending.”

THOUGHTS FOR THE NEXT YEAR (12-14 MONTHS)

“I think, fundamentally, we know what the problems are: it’s debt.”

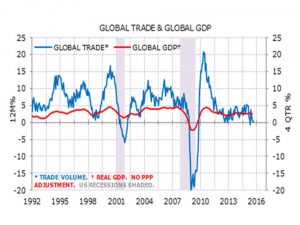

It built up in the system, it’s not properly funded, we know the global imbalances are unsustainable, and add on top of that the financialization of the economy where people are rewarded for trading claims on real cash flows and real assets.

“You have financial institutions which are too big to fail but too big to jail, and frankly, too big to regulate or too big to manage.”

So all of those we know, and on top of that there’s climate issues, resource scarcity, so we’ve got a very toxic set of problems. Things are going to play out in one of three scenarios. One is the ‘Lazarus economy’, where all the skeptics are wrong and everything goes back to normal. It’s not likely, but it might happen. The most likely one is a period of stagnation, which might happen with a 70% chance. What happens is we’re stuck in this environment of very low growth, disinflation, the debt keeps building up, we use policies like financial repression and low interest rates in a predominant way, and we stretch this out for as long as we possibly can. One lesson we learned from Japan is that we can’t do this for a very long time. The policy makers are going to try to keep this game going for as long as possible. The problem is that it’s not sustainable.

The last scenario is the one with the 30% chance, which is the crash. The question is whether that happens suddenly, or if we get gradually to where the system breaks down. You have all these nodes of instability going on and it’s all held together by chicken wire, which is basically central banks putting more and more money in and coming up with more and more far fetched and less effective schemes.

The last scenario is the one with the 30% chance, which is the crash. The question is whether that happens suddenly, or if we get gradually to where the system breaks down. You have all these nodes of instability going on and it’s all held together by chicken wire, which is basically central banks putting more and more money in and coming up with more and more far fetched and less effective schemes.

The crucial thing that people forget is that this is the ultimate act of faith. The central bankers who completely misread things in the lead-up to 2007 and contributed to the crisis have suddenly after that becomes the saviors.

“At some point in time it’ll turn into, ‘oh dear, the emperor has no clothes, they don’t actually know what they’re doing’.”

What people need to keep in mind is that it’ll be very different from 2007-2008. The problem is much bigger, and the emerging markets that were a source of strength in 2008 and provided demand for the people in advanced economies, along with abundant savings that helped push the problem, are no longer a source of strength. The third thing is the fact that the policy makers are all wrong. The social and political pressures are in a much worse place than 2007-2008 and socially the tensions are starting to build up.

“Whatever happens now will be far more difficult to control than they were in 2007-2008 and I think essentially we are at a very dangerous inflection point… And the one thing I do know is if something cannot go on, it won’t go on, and if something happens it happens suddenly.”

The central banks have this under control for the moment, but in complex systems they tip over extremely suddenly and extremely quickly, and none of us know what the trigger will be, but there will be a trigger and in hindsight it would be obvious it was the trigger.

“Everyone now is chasing risky assets because it’s the only way they can feed themselves.”

INVESTMENT DIRECTION AND PREPARATION

“In this crazy world of the 1980s onward, we sort of reversed priority and put capital gains first, income next, and security of capital last.”

You have to think about how to recover, rather than worry about capital gain. One of the key things is to find things that people need: food, oil, scarce resources, and guns (security).

“You’re looking for areas that are absolutely crucial in the terms of the actual needs of ordinary people, and that will be protected.”

The policies are hugely repressive because they’re forcing people to take risks with their savings, and intentionally they’re going to go broke or grow poorer over time.

“I’m actually astonished, when you mentioned pitchforks earlier, that investors haven’t picked up their pitchforks and gone after some of these policy makers, though given time I suspect that’s going to happen.”

VIEWS ON CHINA

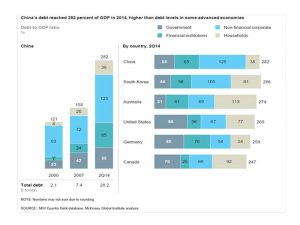

The pre-2008 period was very sound, but after that the Chinese Public Bureau placed a strong emphasis on social stability and launched a program to create employment opportunities. What that’s done is increased the amount of debt in China. In 2000 the amount of debt was $2T. In 2007 it went to $7T. In 2014 it’s $28T. It’s gone up by a factor of 14 times.

“You can’t have that kind of growth being leveraged by debt in a financial system without consequences.”

If you look at where the money’s gone, it’s this massive overcapacity in their industries, there’s a lot of real estate; about 15-20% of China’s GDP is tied up in real estate. It’s inevitable that they’re going to have some problems. The last few debt crises that happened in China, the States stepped in, created asset management companies, bought the bad loans to the banks, selected government guarantees on some bonds, and sold it back to the same banks and let time to take care of the problem.

If you look at where the money’s gone, it’s this massive overcapacity in their industries, there’s a lot of real estate; about 15-20% of China’s GDP is tied up in real estate. It’s inevitable that they’re going to have some problems. The last few debt crises that happened in China, the States stepped in, created asset management companies, bought the bad loans to the banks, selected government guarantees on some bonds, and sold it back to the same banks and let time to take care of the problem.

The problem now is the bad debt problem is much larger, and they’re not going to have the same GDP growth that they had. The way that they’re trying to deal with this is by keeping deposit rates low and the system very liquid so the banks can gradually absorb these losses.

“I think the best case is that China becomes like Japan, which is putting all these bad debts on their balance sheet and gradually slowing down.”

The problem is if they miscalculate, the problem is bigger and comes upon them in a way that is much quicker that you could potentially get a banking meltdown. The problem with that is that would spread from China out very quickly because there’s about a trillion dollars of exposure that far end lenders have to Chinese banks and Chinese companies.

Abstract by: Annie Zhou <a2zhou@ryerson.ca>

Video Editor: Min Jung Kim minjung.kim@ryerson.ca

05/12/2016 - Satyajit Das: DISCUSSES FINANCIAL REPRESSION & THE AGE OF STAGNATION

05/12/2016 - Satyajit Das: DISCUSSES FINANCIAL REPRESSION & THE AGE OF STAGNATION